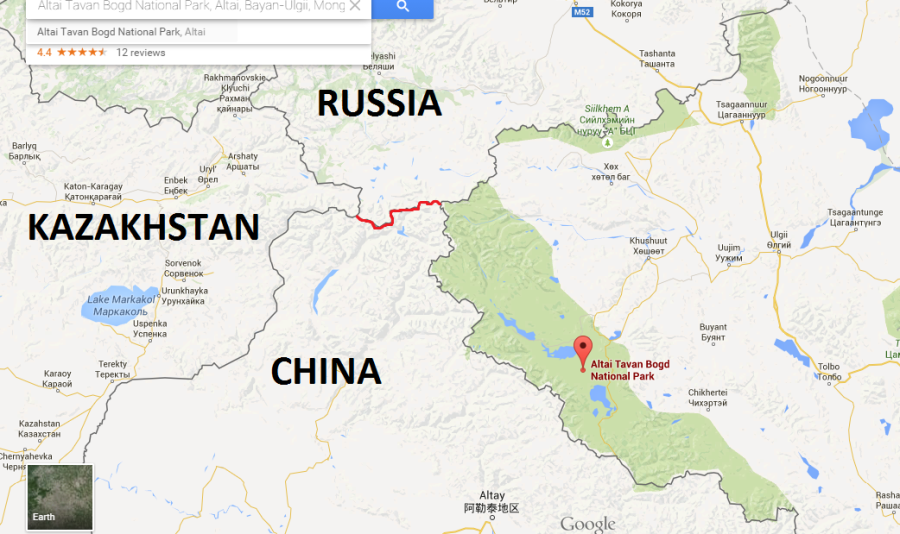

Altai Tavn Bogd National Park is the large green patch near the centre of this map along the border with China. Note that the squiggly red line in the middle is the 38 kilometre stretch of border between China and Russia that separates Mongolia from Kazakhstan.

Located in the remote northwestern corner of Bayan Olgii aimag (province), which is in turn located in the remote northwestern corner of Mongolia, Altai Tavan Bogd National Park spans 6362 square kilometers of pristine alpine wilderness right on the border of both Russia and China. The western boundary of the park marks the Chinese border, while the northern boundary marks the Russian border. Tavan Bogd means “Five Saints” in Mongolian and refers to the five highest peaks inside the park, which includes Mongolia’s highest peak, Khuiten Uul (“Cold Mountain”) at 4,376 metres. The summit of Khuiten also marks the Sino-Mongolian border. The “Five Saints” belong to the Altai mountain range of Central Asia, which spans Mongolia, China, Russia and Kazakhstan. In addition to the “Five Saints”, the park also includes several stunning alpine lakes, as well as three areas containing thousands of ancient petroglyphs and Turkic monoliths, which are listed together as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The park is also home to an abundance of wildlife, including argali (a rare, large-horned species of wild sheep), ibex (a wild goat with long scimitar-shaped horns), deer, moose, wolves, foxes, lynx, brown bears, and even snow leopards. Another attractive feature of the park is the almost complete lack of anthropogenic influence on the landscape; for instance, there are no paved roads, fixed paths or signs. Visitors have to be fully self-sufficient and able to read a topographic map!

We didn’t arrive at the entrance to the park until just after 2pm, which was quite a bit later than we had expected (we had hoped to arrive before noon). Actually, our driver didn’t even drop us at the official entrance to the park, but instead stopped at a local herders wooden cabin, which was located at least 3 kilometres from the park entrance. We didn’t know this at the time, otherwise I would have asked him to drive us right up to the park entrance, since we had paid a king’s ransom for the ride. The main purpose of visiting the park was to try to climb Mongolia’s highest peak, which meant we still had to hike to basecamp. From the park entrance it was a 14 kilometre hike to the basecamp of Khuiten Uul, which we wanted to do that day, so adding a few more kilometres to the hike wasn’t ideal. Since it was already quite late in the day to begin such a hike, I think our driver stopped at the cabin because he expected we would stay a night there and begin our hike the next morning. Dion and I were adamant about leaving as soon as we stepped foot out of the jeep though and even refused an offer of tea with the driver and the residents of the cabin, which in hindsight was probably a bit rude. Just after setting off, I decided to take a couple of things out of my bag, including a small bottle of vodka, to lighten the load a bit, so I walked back to the cabin and asked if I could leave them there, which the owner kindly obliged. Even after shedding 1-2 kg of unnecessary weight though, my bag probably still weighed somewhere between 20-25 kg.

Entrance to Altai Tavn Bogd National Park. There was only this sign to indicate that we were at the entrance of the park, there were no buildings or park staff to greet us. We had to apply for a border permit from the Mongolian military to enter the park, and were told that park rangers or border patrol soldiers inside the park might approach us at any time and ask to see the permit at anytime, but we didn’t see either during the 4 days we were inside the park.

Entrance to Altai Tavn Bogd National Park. There was only this sign to indicate that we were at the entrance of the park, there were no buildings or park staff to greet us. We had to apply for a border permit from the Mongolian military to enter the park, and were told that park rangers or border patrol soldiers inside the park might approach us at any time and ask to see the permit at anytime, but we didn’t see either during the 4 days we were inside the park.

After just a few kilometers, we were really beginning to feel the weight of our packs.

After just a few kilometers, we were really beginning to feel the weight of our packs.

The scenery was absolutely spectacular!

The scenery was absolutely spectacular!

The snow was quite deep in places, which really slowed us down. It was also slightly frustrating and unnerving because we never knew when we were going to suddenly sink up to our knees or even higher. Some of the snow was hard enough to walk right on top of but you could just as easily sink up to your waist at any given moment; trying to crawl out with our heavy packs was tiresome and time-consuming.

I must have sunk up to my knees like this at least 3 dozen times the first day.

I must have sunk up to my knees like this at least 3 dozen times the first day.

Dion slogging his way across a snow field. Neither of us were quite sure if we were going the right way since there was no path to follow.

Dion slogging his way across a snow field. Neither of us were quite sure if we were going the right way since there was no path to follow.

Luckily I had bought a fairly detailed 1:500,000 scale topographic map of the area at a mountaineering store in Ulaan Baatar called Sevin Summits, which was indispensable for navigating through the park without a guide. There was absolutely no sign of a path anywhere; instead we had to navigate using mountains as landmarks. The owner of Blue Wolf Travel, a travel company and hostel in Olgii, the capital of Bayan Olgii province, had marked the route on our map with a pen but it was still a challenge to navigate because of the size of the area and complete lack of a path or any signage to indicate that we were going in the right direction. We weren’t really afraid of getting lost but we worried that we weren’t taking the most direct route, and didn’t want to waste precious daylight on necessary detours. For instance, when we were crossing a large snow field, I suddenly stepped into a pool of ice-cold water hidden beneath the snow, completely submerging my boot. Shocked, I looked around and quickly realized that I had come to a large swathe of still, shallow water. I tried to go around it but discovered to my dismay that the water stretched for at least a kilometer to my left and right. I could see that it was only about 30 metres across though, so I decided to try my luck and walk as nimbly as I could over patches of ice and snow. Unfortunately, this didn’t really work and I ended up sinking into the water at least every other step. If there had been a clearly marked path though, I probably wouldn’t have stumbled into this predicament. Thankfully, my gore-tex lined mountaineering boots are fairly water-resistant, so my feet stayed relatively dry, although my boots froze solid that night. Dion had earlier decided to take a longer route across the snow field, so he didn’t have the same problem, but his detour added about an hour to his hike.

Once I was back on dry land, I quickly found a patch of grass to pitch our tent. It was already after 7 and we had been hiking for 5 hours straight, with the exception of a few 5 minute water breaks. Dion and I had agreed earlier to stop hiking by 7pm so that we would have enough time to pitch our tent and make camp before sunset. It was the end of April and we were at an altitude of about 3,000 metres, so the temperature really began to dip once the sun began to set. It was also very windy, so the wind chill made it feel quite a bit colder. In fact, our first night in the park was much colder than expected. I had a down sleeping bag that’s supposed to keep me comfortably warm down to minus 10 Celsius (and alive at – 20), so I thought it would be fine to just sleep in my long underwear, but I was wrong. The temperature was at least 10 degrees during the day in the sun, but it dropped well below – 10 at night, so I had to get up in the middle of the night and put on all my layers to keep warm, which was a bit of a nuisance. My discomfort was also compounded by a chest cold that was getting worse, to the point where I worried that I may not be well enough to climb the mountain.

Our camp site on the first day. You can see the large, meandering swathe of shallow water in the background. The water was frozen solid when we woke up the next morning but this photo was taken at about 10am, so the sun was already beginning to melt the ice.

Our camp site on the first day. You can see the large, meandering swathe of shallow water in the background. The water was frozen solid when we woke up the next morning but this photo was taken at about 10am, so the sun was already beginning to melt the ice.

We decided to sleep in a bit the first morning and take our time packing up because we thought we only had a short hike ahead of us to reach basecamp. Once again, we were wrong. It took another 6 hours of nonstop hiking before we finally reached basecamp early that evening, which was somewhere between two to three times longer than we had expected. Part of this was because of the snow. Deep snow in many areas had slowed us down considerably and concealed any sign of a foot path that would have offered a more direct route. Instead, we had to more or less wing it with the help of the map. Again, we knew were going in the right general direction but had to occasionally readjust our route, which involved quite a bit of meandering and even backtracking.

The scenery was even more spectacular on the second day!

The scenery was even more spectacular on the second day!

We even saw fresh bear tracks, which added to the excitement of being in a pristine alpine wilderness.

We even saw fresh bear tracks, which added to the excitement of being in a pristine alpine wilderness.

Dion walking on top of a moraine next to the 22km long Potaniin glacier, which leads to the foot of Khuiten Uul.

Dion walking on top of a moraine next to the 22km long Potaniin glacier, which leads to the foot of Khuiten Uul.

A good vista of Khuiten Uul. The cairn on the lower left of the photo is just above basecamp.

A good vista of Khuiten Uul. The cairn on the lower left of the photo is just above basecamp.

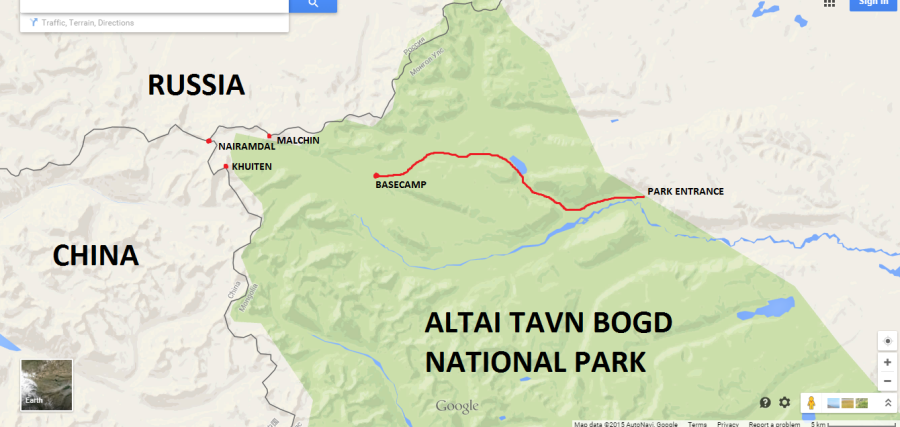

The red line shows the rough route we took from the entrance of the park to basecamp. The three main peaks in the park, Khuiten, Nairamdal and Malchin are marked with red dots at the top right corner of the park, along the borders of China and Russia. Nairamdal, which means “Friendship” in Mongolian actually marks the border of all three countries, while Malchin borders Russia and Khuiten borders China.

The red line shows the rough route we took from the entrance of the park to basecamp. The three main peaks in the park, Khuiten, Nairamdal and Malchin are marked with red dots at the top right corner of the park, along the borders of China and Russia. Nairamdal, which means “Friendship” in Mongolian actually marks the border of all three countries, while Malchin borders Russia and Khuiten borders China.

We arrived at basecamp at about 6pm. The hike had been quite pleasant for most of the day, but as my bad luck would have it, I ended up stepping into another pool of ice water, this time completely submerging my boots and soaking my feet. It happened at about 5 pm, just as we were about to take a break. Dion had suggested the break and was about to sit down when I pointed to a large rock about 20 metres ahead and suggested that we sit there instead. Big mistake. Just a few metres before I arrived at the rock, I suddenly sank up to my thighs in snow, at which point I immediately felt a surge of icy water flood into my boots. There was nothing the goretex lining on my boots could do to protect my feet in that much water, which went up to my knees. I quickly jumped out of the water but my feet were already sopping wet. All I could do was take my boots off, wring out my socks and put a new pair on. Unfortunately, the new pair got soaked almost as soon as I put my boots back on because the insides were so wet. I had to continue hiking in soaking wet boots for another hour, which wasn’t as bad as I had anticipated. My feet actually warmed up quite a bit after the initial soaking, but when we arrived at basecamp, they quickly cooled down, to the point that I was worried I might get frostbite during the night if I couldn’t warm them back up. I didn’t have any more dry socks at that point, so I wasn’t sure if I would be able to keep my feet warm enough in my sleeping bag. My boots were also completely soaked and froze solid again that night.

We knew we had arrived at basecamp when we stumbled upon a small pile of bottles and tin cans, and spotted a small hut a few hundred metres away. On closer inspection, we realized that the hut, which was well constructed and looked brand new, was actually an outhouse. It turns out that it had actually been built with funds from the EU, which in my mind is a good use of development aid. It may only represent a very modest contribution to Mongolia’s development, but a simple outhouse can have the effect of promoting responsible eco-tourism, which is good for the local economy and environment. It also served another unintended, yet no less beneficial, purpose for us. While we were trying to pitch our tent a few hundred metres from the outhouse the wind was really raging, which made the task quite difficult. Suddenly, a light bulb went off in Dion’s head and he suggested that we try to sleep in the outhouse! Contrary to popular beliefs about outhouses and past experiences with them throughout my travels in the developing world, this outhouse was actually very clean. In fact, it didn’t even smell like an outhouse. This was mainly due to the fact that it was brand new but also because whatever excrement was at the bottom of it (I don’t think there was much) was completely frozen and buried by a deep blanket of snow that had blown into it. Since it was so clean, we figured it would make a more comfortable, sturdy and convenient shelter than our tent. The only thing it required was a bit of wind-proofing, which we accomplished by tying the panels of our tent to the outside of it.

Dion boiling a pot of water on our portable butane stove inside the outhouse. Notice how hard the wind is blowing by the concave shape of the tent behind his head.

Dion boiling a pot of water on our portable butane stove inside the outhouse. Notice how hard the wind is blowing by the concave shape of the tent behind his head.

The outhouse, which we later called our “toilet bivy”, actually made for a surprisingly comfortable shelter, even more so than our tent because it was much more spacious and easier to enter and exit. It wasn’t warm by any means and probably wasn’t as windproof as our winter tent, but we slept comfortably enough given the subzero temperatures at night. Fortunately, Dion lent me a pair of socks, so my feet didn’t freeze and I was even able to dry my wet socks by putting them at the bottom of my sleeping bag while I slept. My boots, on the other hand, were completely frozen the next morning and became soaked when they thawed out in the sun, so it took several more hours before they were dry enough to wear.

Originally, we had planned to spend one night in the outhouse then hike up to advanced basecamp (ABC), which was on top of the Potaniin glacier right at the foot of the mountain. We were told that it was a 5 hour hike from basecamp to ABC then another 6 hours of climb from ABC to the summit of Khuiten Uul, so we planned to hike up to ABC on the third day, pitch our tent, then wake at 3am on the fourth day and try for the summit. If all went according to plan, we would be back safely at basecamp at 2pm on the fourth day. Unfortunately, not much had gone according to plan during our time in Mongolia. The wind had howled relentlessly during our second night in the park and hadn’t let up on the morning of the third day, so we were reluctant to try to pitch our tent at ABC, where it was sure to be far windier. My soaking wet boots were another problem but even worse were the massive blisters they had caused on my heels.

Both my heels looked like this.

Both my heels looked like this.

I had tried to protect my heels with gauze but this did very little to prevent them from rubbing very painfully against the inside of my boots. By the end of the second day in the park, my blisters had transformed into bleeding open wounds and I could barely sleep that night because of the pain. I had recently bought my first pair of proper mountaineering boots and this was my first time wearing them, so I was expecting to get blisters, but nothing that bad. The main concern, though, was the wind. We both agreed it would be a good idea to wait one more day for the wind to die down before pitching camp at ABC and attempting the summit, so we decided to stay at basecamp another night.

We spotted this grey wolf (centre of photo where snow field meets grass) from the outhouse on the morning of our third day in the park, which was very exciting! It was running in the distance then suddenly stopped to look at us for a moment, before continuing up over the moraine on the right and out of sight.

We spotted this grey wolf (centre of photo where snow field meets grass) from the outhouse on the morning of our third day in the park, which was very exciting! It was running in the distance then suddenly stopped to look at us for a moment, before continuing up over the moraine on the right and out of sight.

We hung out at basecamp all morning on the third day but started getting pretty antsy by noon, so decided to scope out the route to ABC and see what conditions were like on the glacier, which we needed to cross to get to ABC and onto the mountain. When we were in the provincial capital Olgii waiting for military border permits to enter the park, the owner of Blue Wolf Travel told us that he heard it had snowed heavily in the park about 10 days prior. He warned us this would probably make crossing the glacier more difficult and dangerous, so we thought it would be a good idea to use our day off to do some reconnaissance before attempting to hike to ABC with all our gear. We also wanted to judge if it would be feasible to bypass camping at ABC entirely and instead hike directly from basecamp to ABC carrying only small day packs and then push for the summit the same day. We had read reports online from previous climbers of Khuiten Uul that camping at ABC wasn’t necessary. Instead, they suggested going directly from basecamp to the summit in one day. However, according to the estimated times we had been told it takes to hike from basecamp to ABC (5 hours), then climb from ABC to the summit (6 hours), we thought it would be prudent to first see for ourselves what conditions were like on the route to ABC. In addition to hiking and climbing 11 hours in a single day from basecamp to the summit, it would take an estimated 5 hours to get back down to basecamp as well, for a total of 16 hours of continual hiking and climbing, which would make for a very long and exhausting day! If the wind didn’t die down by the next day though, we reasoned that this is what we would have to attempt, since trying to camp at ABC in high wind seemed like an even less attractive idea. We decided that if the route to ABC was good and we made it there quickly, we would come back to basecamp and wait to see if the wind died down that night; if it did, we would hike to ABC with our gear the next day, pitch our tent, and try for the summit early the next morning. However, if the wind did not die down that night, we decided to just wake up at 3 am the next morning and try for the summit directly from basecamp.

We set out at about 2pm with a full bottle of water each (750 ml) and some nuts. The weather was great, so we were in high spirits. My heels hurt like hell at first, but I became numb to the pain after about 2 hours.

A dramatic view of the moraine in front of the Potaniin glacier, with snow and ice-covered peaks behind.

A dramatic view of the moraine in front of the Potaniin glacier, with snow and ice-covered peaks behind.

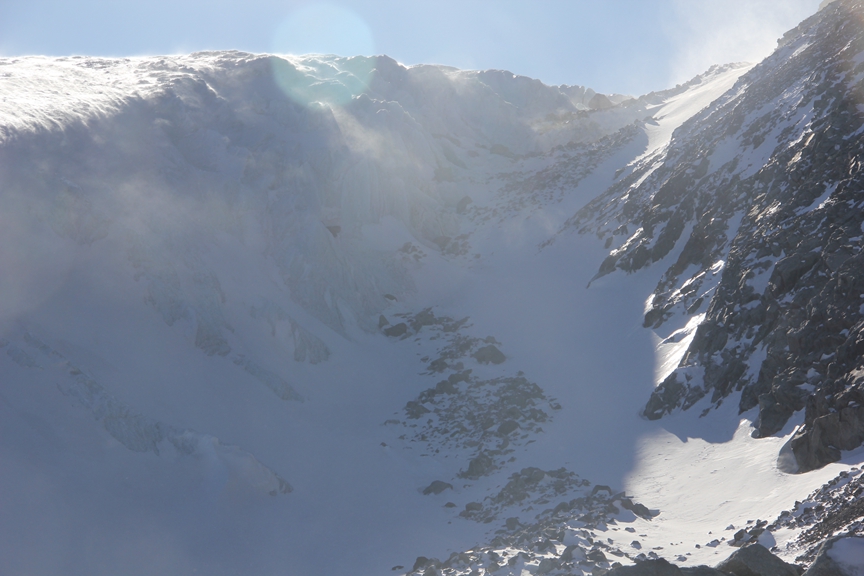

Seeing large plums of snow blow off the summit of Khuiten like this wasn’t encouraging. The amount of snow covering the mountain was also a concern. Snow usually only covers the top third of the mountain during summer, which is when most people attempt to climb it.

Seeing large plums of snow blow off the summit of Khuiten like this wasn’t encouraging. The amount of snow covering the mountain was also a concern. Snow usually only covers the top third of the mountain during summer, which is when most people attempt to climb it.

After an easy to moderate 2 hour hike along a foot path that ran beside the moraine of the Potaniin glacier, we came to the base of a 4,050 metre peak called Malchin, which is right on the border of Mongolia and Russia. At that point, the path disappeared and the terrain became increasingly difficult to traverse, with deeper snow and bigger rocks to contend with.

Dion standing at the foot of Malchin.

Dion standing at the foot of Malchin.

Taking a much-needed water break.

Taking a much-needed water break.

We walked along the foot of Malchin for about an hour, between the moraine (grey rock on right, just to left of glacier) and the pile of rocks that Dion is standing on in this photo. Eventually, the snow became too deep at the foot of the mountain, so we decided to try to walk up along the side of the mountain instead.

We walked along the foot of Malchin for about an hour, between the moraine (grey rock on right, just to left of glacier) and the pile of rocks that Dion is standing on in this photo. Eventually, the snow became too deep at the foot of the mountain, so we decided to try to walk up along the side of the mountain instead.

I walked across this section of scree, which was difficult and dangerous, because I thought it would be faster than walking at the foot of the mountain, where deep snow had accumulated. Dion followed me for a while but soon thought better of it and walked back down to the base of the mountain, which was slower but probably a better decision. I certainly did not enjoy walking this section, even though it saved me a bit of time.

I walked across this section of scree, which was difficult and dangerous, because I thought it would be faster than walking at the foot of the mountain, where deep snow had accumulated. Dion followed me for a while but soon thought better of it and walked back down to the base of the mountain, which was slower but probably a better decision. I certainly did not enjoy walking this section, even though it saved me a bit of time.

This turned out to be the most difficult and dangerous section of the route. By this point we had almost thrown in the towel. The path had long since ceased to exist and we started to doubt that we would ever be able to make it to ABC in the estimated 5 hours that we were told it took to reach it from basecamp. I really wanted to get on top of the glacier though, both to get a view of ABC and try to judge how long it would still take to get there, and also see if it would even be possible given how much snow was on the glacier. From this point onwards, difficult hiking gave way to dangerous climbing.

This turned out to be the most difficult and dangerous section of the route. By this point we had almost thrown in the towel. The path had long since ceased to exist and we started to doubt that we would ever be able to make it to ABC in the estimated 5 hours that we were told it took to reach it from basecamp. I really wanted to get on top of the glacier though, both to get a view of ABC and try to judge how long it would still take to get there, and also see if it would even be possible given how much snow was on the glacier. From this point onwards, difficult hiking gave way to dangerous climbing.

Towering above me are large seracs, huge chunks of ice hanging off the side of the glacier. I was smiling because it was exciting to be there but it was also extremely unnerving to stand directly underneath such massive columns of ice.

Towering above me are large seracs, huge chunks of ice hanging off the side of the glacier. I was smiling because it was exciting to be there but it was also extremely unnerving to stand directly underneath such massive columns of ice.

The route was fraught with danger from objective hazards like falling rocks and seracs, which can come tumbling down and crush a person at any moment.

The route was fraught with danger from objective hazards like falling rocks and seracs, which can come tumbling down and crush a person at any moment.

We felt a lot safer once we were higher up the glacier and no longer standing directly underneath seracs and giant boulders resting precariously on the ice, but there was still plenty of danger to worry about.

We felt a lot safer once we were higher up the glacier and no longer standing directly underneath seracs and giant boulders resting precariously on the ice, but there was still plenty of danger to worry about.

The undulating waves of ice on the glacier were stunningly beautiful.

The undulating waves of ice on the glacier were stunningly beautiful.

Once on top of the glacier we could finally see ABC, which is just behind the low dark hill in the centre of this photo.

Once on top of the glacier we could finally see ABC, which is just behind the low dark hill in the centre of this photo.

It should have been just a short hike across the glacier to ABC but deep snow made the prospect of crossing the glacier extremely risky. The danger of falling into deep hidden crevasses was very real and deadly serious. We had read reports online from past climbers who said they had passed several crevasses on their way to ABC and they warned other climbers to be very careful of them when crossing the glacier. However, the problem for us was that we simply had no way of knowing where the crevasses were because of the fresh blanket of snow covering the glacier. Most people who attempt to climb Khuiten do so from July to September when most of the snow on the glacier has melted, which, of course, makes the crevasses much more visible and easier to avoid falling into. Unfortunately, we were attempting to climb it in late April, when there was still plenty of snow.

The ridge on the right side of this photo marks the Russian border. The low-lying peak at the end of the ridge (just right of centre) is the 4,180 metre Nairamdal Peak, which marks the tripoint border of Mongolia, China and Russia. ABC is just behind the closest dark peak on the left side of the photo.

The ridge on the right side of this photo marks the Russian border. The low-lying peak at the end of the ridge (just right of centre) is the 4,180 metre Nairamdal Peak, which marks the tripoint border of Mongolia, China and Russia. ABC is just behind the closest dark peak on the left side of the photo.

The red line in this satelitte image indicates the route we took from basecamp to where we stopped on the edge of the upper reaches of Potaniin glacier. Red dots also mark Advanced Basecamp (ABC), Malchin peak, which is right on the Russian border, Nairamdal peak, which is mentioned above, and Khuiten, which is right on the Chinese border.

Close up of the glacier and Russian border at top of the ridge. Note how much snow is on the glacier.

Close up of the glacier and Russian border at top of the ridge. Note how much snow is on the glacier.

Holes in the snow exposing a deep crevasse. I didn’t want to get any closer, so this photo doesn’t show how deep the crevasse goes, but suffice it to say I couldn’t see the bottom.

Holes in the snow exposing a deep crevasse. I didn’t want to get any closer, so this photo doesn’t show how deep the crevasse goes, but suffice it to say I couldn’t see the bottom.

No sooner than I had finally stepped foot up on top of the edge of the glacier, I very nearly fell into a crevasse. I had gone ahead of Dion, which in hindsight was a stupid idea, and was traversing a small section of rock and snow, when I noticed that there were deep holes in the snow less than a metre to my right. On closure inspection, I could see that they were the opening to a deep crevasse, so deep that I couldn’t see the bottom of it. At this moment, I finally realized that crossing the glacier in such conditions was tantamount to playing Russian Roulette. I was very much shaken by having come so close to falling into a crevasse. If there hadn’t already been holes in the snow, which exposed its presence, I very well could have stepped on the snow covering it and fallen into the abyss.

A good close up shot of Khuiten.

A good close up shot of Khuiten.

It should have been a straight forward 6 hour climb up the north ridge to the summit but the extreme risk of falling into a crevasse while crossing the glacier was simply not worth taking. It was very difficult to turn back, though. We had spent 9 days just trying to get to this point but knew we had to retreat. It simply would have been suicide to keep going.

Disappointingly, this was as close as we got to Khuiten on this trip.

Disappointingly, this was as close as we got to Khuiten on this trip.

It had taken us a good 4 hours to get onto the top of the glacier, which meant we had to move fast in order to make it back to basecamp before dark. Heading back down the steep section of the glacier was just as nerve-racking as ascending it, probably even more so.

It was a mild consolation to see such a beautiful sunset after a long and disappointing day.

It was a mild consolation to see such a beautiful sunset after a long and disappointing day.

After roughly 2 hours of moving as fast as we could, we reached basecamp just before dark. Our second night in the outhouse passed without incident and we woke up early the next morning, intending to get an early start on the hike from basecamp back to the entrance of the park.

Saying one last goodbye to Khuiten (far right). We promised ourselves we would return and try for the summit again at a safer time of year.

Saying one last goodbye to Khuiten (far right). We promised ourselves we would return and try for the summit again at a safer time of year.

Holding up the flag for an outdoor store in Beijing where we buy a lot of gear and are friends with the owner.

Holding up the flag for an outdoor store in Beijing where we buy a lot of gear and are friends with the owner.

Dion really loves his Czech made walking sticks!

Dion really loves his Czech made walking sticks!

I spotted this fox on our way out of the park.

I spotted this fox on our way out of the park.

To see more photos from the park, please click here.

This is the wooden cabin where our driver dropped us off 4 days prior. We came back to pick up the things I had left there before entering the park. It took me just over 5 hours to reach it from basecamp, which is less than half the time it took us to hike from there to basecamp.

This is the wooden cabin where our driver dropped us off 4 days prior. We came back to pick up the things I had left there before entering the park. It took me just over 5 hours to reach it from basecamp, which is less than half the time it took us to hike from there to basecamp.

The cabin isn’t connected to the electric power grid, which is over 100 km away, so the small black and white TV in the top left of the photo was powered by a car battery. There was also a small solar panel outside for powering the energy-saving bulb hanging from the ceiling.

The cabin isn’t connected to the electric power grid, which is over 100 km away, so the small black and white TV in the top left of the photo was powered by a car battery. There was also a small solar panel outside for powering the energy-saving bulb hanging from the ceiling.

The residents of the cabin are “poor” by modern standards because they lack a reliable source of electricity, indoor plumbing, modern home appliances or communication equipment like mobile phones and computers, but by the standards of their traditional lifestyle, in which wealth is measured in livestock, not money, they seemed to be doing quite well. They had a large herd of goats and sheep as well as several yaks and horses. They also had several old Soviet era Russian vehicles and a Chinese motorcycle, so obviously weren’t poor by Mongolian standards. However, the extreme remoteness of where they live would likely cause some hardship, logistics being primary among them. For instance, the nearest town, which is itself very remote, is 110 km away and the “road” leading to it is very rough. Nothing more than a jeep track, the “road” can only be traversed by 4 wheel drive off-road automobiles or motorcycles at a maximum speed of 20-30 kilometres per hour. Access to adequate healthcare is also another significant challenge.

Like most people in this part of the world, the residents of the cabin were very hospitable. As soon as I arrived, they welcomed me inside their humble but colourfully decorated, single room cabin and offered me milk tea and an assortment of homemade cheeses and biscuits. In turn, I gave their children several Snickers bars that I had in my bag. I also gave them most of my left over food, including at least a kilo of millet and noodles, and a wool sweater that a Canadian friend in Beijing had asked me to give to someone the next time I went traveling in a poor, remote area. The diet of most rural Mongolians consists mainly of milk, cheese, meat and fat from their own herds of goat, sheep, yaks and camels. They also consume limited amounts of grain but hardly any vegetables. It’s actually quite astonishing that they can consume so much meat and so few vegetables but still remain healthy. Apparently, this is because they also consume large quantities of fermented dairy products, like cultured milk, curd and various cheeses, which are loaded with healthy bacteria or “probiotics”.

This table was full of an assortment of homemade cheeses and curd, chewy deep-fried dough and bowls of salty milk tea.

This table was full of an assortment of homemade cheeses and curd, chewy deep-fried dough and bowls of salty milk tea.

The view out the cabin window.

The view out the cabin window.

Interestingly, this girl had naturally golden blond hair, which is quite unusual for someone with otherwise typical “East Asian” facial features.

Interestingly, this girl had naturally golden blond hair, which is quite unusual for someone with otherwise typical “East Asian” facial features.

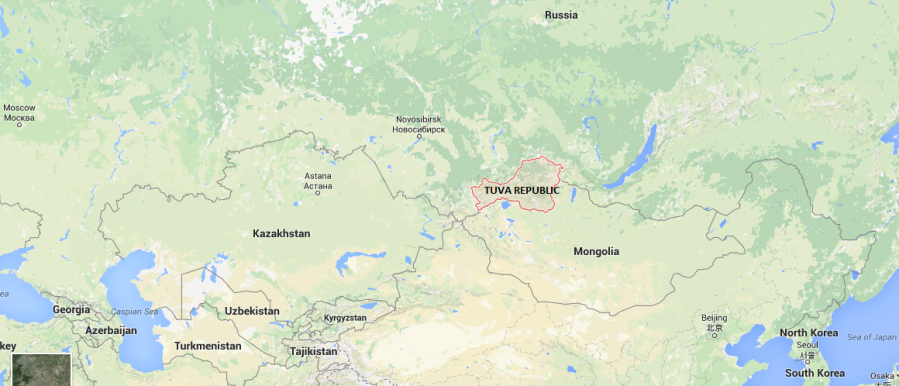

The residents of the cabin actually weren’t ethnically Mongol or Kazakh but Tuvan, a small Turkic-speaking ethnic group concentrated in southern Siberia, which borders this remote and isolated corner of Mongolia. There are only about 5,000 Tuvans in Mongolia and close to 4,000 just across the border in China’s Xinjiang province, but the vast majority of Tuvans, about 270,000, live in the Tuva Republic, a nominally autonomous “federal subject” of Russia, which was established as a “homeland” for the Tuvan people, who make up the vast majority of their self-styled “republic”.

The “Tuva Republic” is outlined in red on this map.

The “Tuva Republic” is outlined in red on this map.

A very large, but thankfully friendly, sheepdog.

A very large, but thankfully friendly, sheepdog.

We knew that once we made it out of the park, we would probably have to hire a local driver to drive us along the very rough road to the nearest village, Tsengel, which is 110 km away. There is no public transport running between the park and Tsengel and we knew it would be nearly impossible to hitchhike since there was so little traffic on the road, so we decided to ask the residents of the cabin if they would be willing drive us to Tsengel for a fee. Since we had paid $180 USD for a jeep to drive us 180 km from Olgii to the park, we estimated it would cost about $100 USD for a drive to Tsengel, which is precisely how much they charged us. Although we weren’t very enthusiastic to pay so much, we were in a very poor bargaining position. Our only alternative would have been to walk the 110 kilometres to Tsengel, but that would have taken us at least 4-5 days and wouldn’t have been very enjoyable with heavy packs, particularly for me, since the blisters on my heels were still quite painful.

To read about the entire Mongolian journey that this adventure was a part of click here.