In June 2015 I travelled from my home in Beijing to Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in China’s southwest, in order to try climbing a 5355 metre high mountain that is frequently climbed by novice Chinese mountaineers with the help of professional mountain guides. I’ve long been enamored with mountains for their rugged aesthetic beauty and awe-inspiring enormity but it wasn’t until the beginning of 2015 that I actually got it into my head to actually try climbing one. I have traveled in many mountainous areas throughout Asia, including western China, northern Pakistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Kyrgyzstan, where I’ve hiked in mountainous terrain and even done a few fairly rigorous treks to the base camps of some of the world’s highest peaks, but I had never actually considered learning how to climb mountains with ropes and all the other necessary equipment used by mountaineers to hoist themselves up, and ultimately on top, of mountains.

Map showing the distance between Beijing and Chengdu.

Map showing the distance between Beijing and Chengdu.

The whole mountaineering enterprise not only seemed too dangerous and exhausting but quite technical as well. The thought of learning how to use ropes and crampons and carabineers was simply too daunting to contemplate. That was until I scrambled to the top of a 4300 metre high mountain in a very remote region of Kyrgyzstan in mid January 2015. I don’t consider this a true mountain “climbing” experience though, since I didn’t use ropes or any other professional mountain climbing gear. Instead I think it would be more accurately described as “scrambling”, which in mountaineering parlance refers to the act of hiking up a slope steep enough to require the use of hands but not ropes. I had been horse trekking for a week at an altitude of 3000 metres in the Tianshan Mountains of eastern Kyrgyzstan close to the Chinese border when I suddenly decided to try to scramble alone to the top of a fairly steep, snow-capped mountain one afternoon. When I finally reached the summit, I was astounded by the view that awaited me. It was an ocean of jagged snow-capped peaks for as far as the eye could see. At that moment I knew I wanted to learn how to properly “climb” mountains.

Fast forward six months and I found myself standing at the foot of a 5355 metre high mountain in a protected nature reserve and UNESCO World Heritage Site located on the edge of the Tibetan plateau called Mount Siguniang National Park. “Siguniang” means “Four Sisters” in Chinese and is the name of a group of four peaks that dominate a narrow, pristine and heavily forested alpine valley. The highest of the four is aptly named the “4th Sister” and at a height of 6250 metres, it towers over the other 3 peaks. Although not exceptionally high for western China or Asia more generally, the “4th Sister” is the second highest mountain in Sichuan province and is considered an extremely difficult and dangerous peak to climb. Since it was first climbed by a Japanese expedition in 1981, a mere 30 people are thought to have reached the summit and at least 4 people have died on the mountain. However, the Chinese government doesn’t officially recognize any of the successful ascents.

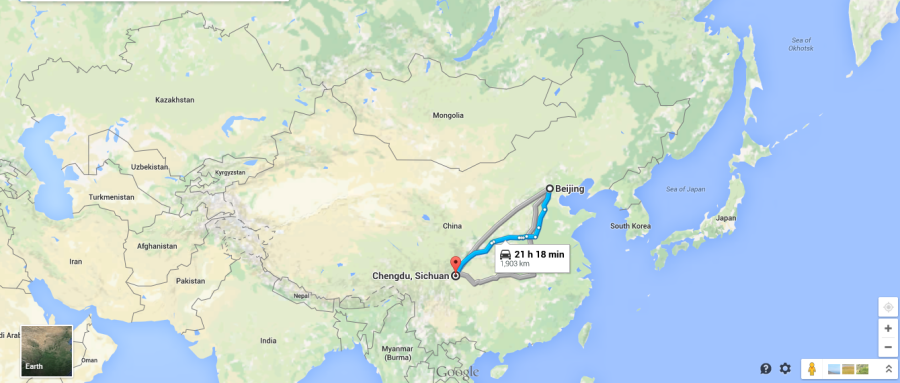

The red pin on this map shows the location of Siguniang National Park.

The red pin on this map shows the location of Siguniang National Park.

Fortunately, the other 3 peaks are much easier to climb and not nearly as dangerous, so I decided to try to climb the highest of those, which is known as the “3rd Sister”. The idea to climb this mountain came from an Australian friend in Beijing who had climbed it in October 2014. He was also the same friend who I teamed up with to travel from Beijing to a remote corner of northwestern Mongolia where we tried to climb that country’s highest mountain in May 2015 but abandoned the attempt for safety reasons.

With a respectable height of 5355 metres above sea level, the “3rd Sister” is considered a challenging peak for novice mountaineers as it requires basic climbing skills and the use of ropes and other safety equipment to summit safely. At 5276 metres, the next highest peak, known as the “2nd Sister” also requires basic climbing skills and the use of ropes but is considered much easier than the “3rd Sister”, while the lowest of the four peaks, the 5025 metre high “Eldest Sister”, can be summited safely without the use of ropes and other mountaineering equipment, so is considered a pure trekking peak. The main attraction of these three peaks for beginner mountain climbers, besides the stunningly beautiful alpine scenery, is both their accessibility and the fact that Chinese mountain guiding companies offer inexpensive, fully guided expeditions to their summits. Since my friend had enjoyed his expedition, I thought it would be a great opportunity to “learn the ropes” of mountaineering, so to speak (pun intended!).

Satellite image showing the four peaks of the Siguniang range and their respective elevations.

Satellite image showing the four peaks of the Siguniang range and their respective elevations.

The setting off point for this expedition was the lovely provincial capital of Sichuan, Chengdu. The mountain guiding company I used had an office in Chengdu and it was from there that they provided transportation in a 4 wheel drive to the small Tibetan town of Rilong, which lies at an altitude of 3,160 metres in a narrow alpine valley at the entrance to Mount Siguniang National Park. The drive from Chengdu to Rilong is only about 230 km but about a third of that is along a very rough unpaved road, while the paved road meanders up and down a mountain via a 4475 metre high mountain pass, so the entire journey took about 6 hours, which included a short stop for lunch.

This satellite image shows the route we took from Chengdu (on right) to Rilong (left). Note the transition from low lying terrain on the right half of the image to mountainous terrain on the left. Chengdu is located in the Sichuan basin, one of the most fertile agricultural regions in China, but is only about a hundred kilometres from the edge of the Tibetan plateau.

This satellite image shows the route we took from Chengdu (on right) to Rilong (left). Note the transition from low lying terrain on the right half of the image to mountainous terrain on the left. Chengdu is located in the Sichuan basin, one of the most fertile agricultural regions in China, but is only about a hundred kilometres from the edge of the Tibetan plateau.

Part of the journey to Rilong passes through Wenchuan County, which was devastated by a powerful earthquake in 2008 that claimed an estimated 88,000 lives. Part of the road through Wenchuan is still in very bad shape and is frequently washed out by flashfloods and blocked by landslides.

Part of the journey to Rilong passes through Wenchuan County, which was devastated by a powerful earthquake in 2008 that claimed an estimated 88,000 lives. Part of the road through Wenchuan is still in very bad shape and is frequently washed out by flashfloods and blocked by landslides.

As we climbed in elevation the road improved considerably and offered some beautiful mountain vistas. Here we’re at about 3000 metres above sea level.

As we climbed in elevation the road improved considerably and offered some beautiful mountain vistas. Here we’re at about 3000 metres above sea level.

This photo shows the road meandering up the mountainside in long, drawn out switchbacks.

This photo shows the road meandering up the mountainside in long, drawn out switchbacks.

At this point we were at about 4000 metres. The fog was very thick so we had to travel quite slowly. We also passed several cyclists who were putting themselves in quite a bit of danger by being on that road in such heavy fog.

At this point we were at about 4000 metres. The fog was very thick so we had to travel quite slowly. We also passed several cyclists who were putting themselves in quite a bit of danger by being on that road in such heavy fog.

The highest point on the journey, Balangshan Pass, 4487 m. At this point I was feeling pretty light headed, having risen from an elevation of only 500 metres in Chengdu over a span of about 5 hours.

The highest point on the journey, Balangshan Pass, 4487 m. At this point I was feeling pretty light headed, having risen from an elevation of only 500 metres in Chengdu over a span of about 5 hours.

Almost as soon as we had crossed the top of the Balangshan Pass, we drove around a bend and began descending into a valley dominated by dramatic peaks.

Almost as soon as we had crossed the top of the Balangshan Pass, we drove around a bend and began descending into a valley dominated by dramatic peaks.

Making our way down the pass through some pretty tight switchbacks.

Making our way down the pass through some pretty tight switchbacks.

About 5 km outside of Rilong town we stopped to take a photo of what we could see of the Four Sisters. The wide mountain on the far left is the “4th Sister”. Although shrouded in clouds, the width of the base offers a clear indication of how much higher the peak is than the other three. Second from the left is the “3rd Sister”, the peak I intended to climb, with the “2nd Sister” second from the right, and the “Eldest Sister” shrouded in cloud on the far right.

About 5 km outside of Rilong town we stopped to take a photo of what we could see of the Four Sisters. The wide mountain on the far left is the “4th Sister”. Although shrouded in clouds, the width of the base offers a clear indication of how much higher the peak is than the other three. Second from the left is the “3rd Sister”, the peak I intended to climb, with the “2nd Sister” second from the right, and the “Eldest Sister” shrouded in cloud on the far right.

Rilong

This satellite image shows the position of Rilong (bottom centre) in relation to Mount Siguniang (left). The squiggly yellow line leading from the top right side of the image to Rilong is the road we took from Chengdu to Rilong. Note the number of switch backs the road has to get through the mountains.

This satellite image shows the position of Rilong (bottom centre) in relation to Mount Siguniang (left). The squiggly yellow line leading from the top right side of the image to Rilong is the road we took from Chengdu to Rilong. Note the number of switch backs the road has to get through the mountains.

Shortly after arriving in Rilong, our driver dropped us off at a small hotel where we checked in. There was only one other client in my group, a 25 year old Chinese guy from Inner Mongolia, so the hotel manager put us in a double room. Like me, the other client had never climbed a mountain with ropes and joined this trip because he wanted to learn. Unlike me though, he hadn’t even scrambled up a mountain before either, but claimed to be an avid hiker. He said he wanted to trek to the basecamp of K2 in Pakistan (for those who don’t know, K2 is the second highest mountain on earth at 8611 metres, only about 240 metres lower than Everest, but much harder to climb and far more remote), which takes seven long, hard days of high altitude hiking over very rough terrain to reach, so he seemed like a serious outdoors enthusiast and mountain lover.

After unpacking, we went down to the hotel restaurant to have dinner, which was already prepared for us as part of the trip package (hotel accommodation was also included), then went back to our room for the night. At about 9pm, three Tibetan guys in there 30’s came to our room. One was the owner of the mountain guiding company and the other two were our guides. They had come to introduce themselves and brief us on the climbing itinerary. They seemed friendly and professional but I was slightly putt off by the way all three puffed away nonchalantly on cigarettes in my room and then threw the butts on the floor. I’ve lived in China long enough not to take this sort of thing personally though. Smoking indoors in China is just about as normal as chewing gum, especially in rural areas, so I chose not to make a fuss about it for fear of offending them. As far as my health was concerned, I considered it more prudent to try to build a good rapport with my guides, since I would be relying on them to guide me up and down the mountain safely. After chatting with them for about 20 minutes, they told us to meet them at 9 the next morning in the lobby and left.

I went to bed at about 10:30 that evening and woke up at 6:30 the next morning feeling well rested. Fortunately, I didn’t feel any adverse effects from the altitude, which could have been an issue, since we had driven from a mere 500 metres above sea level in Chengdu to almost 4500 metres in about 5 hours the day before. Although we spent the night in Rilong at a bit less than 3200 metres, this wasn’t much time to acclimatize to such a high elevation gain in one day.

We had breakfast in the hotel, packed our bags and met our guides in the lobby at 9. Our first stop was the local tourism bureau where our guides helped us register and each buy a 150 RMB (about $25 USD) ticket to enter Mount Siguniang National Park (the ticket price was actually included in the trip price, so the guides bought the tickets). Our guides then drove us to a nearby parking lot where they told us to wait for a shuttle bus that would drive us to the entrance of park. The shuttle bus ride was only a few kilometers and the guides were waiting for us when we arrived, so I’m not quite sure why they put us on the bus in the first place but I suspect it’s a local government rule. Once we were off the bus, the guides put our backpacks into large fertilizer bags and strapped them both to the back of a horse. This came as a pleasant surprise, since the hike to basecamp, located at more than 4400 metres, was estimated to take 4-6 hours and would have been a lot more difficult with a heavy pack on. I had brought my own tent, sleeping bag and lots of warm clothing, among other camping items, so my backpack weighed at least 15 kg.

Basecamp Trek

This satellite image shows the route we hiked from the entrance of Siguniang National Park (bottom star) to basecamp (upper right star), as well as the route we climbed from basecamp to the summit of the 3rd Sister. The four arrows indicate the respective peaks of the Siguniang range.

This satellite image shows the route we hiked from the entrance of Siguniang National Park (bottom star) to basecamp (upper right star), as well as the route we climbed from basecamp to the summit of the 3rd Sister. The four arrows indicate the respective peaks of the Siguniang range.

We set off at 10 am with two horses and two guides. The weather was perfect – sunny, no wind, with a temperature of about 15 degrees centigrade. After walking along a paved road for about half a kilometre, we came to a Tibetan Buddhist lamasery. The lamasery marked the terminus of the road and the beginning of a wooden boardwalk, which led into a dense forest. We walked along the boardwalk for about 500 metres accompanied by one of the guides, while the other guide led the horses along a nearby horse trail. The boardwalk extends the entire length of the valley and is used by ordinary tourists who come to the park to admire the alpine scenery and gaze up at the mountains from a safe distance. I could imagine the boardwalk getting pretty crowded during Chinese holidays but fortunately we didn’t see a single tourist while we were on it. I had heard that Mount Siguniang National Park was tremendously beautiful but hadn’t looked at any photos before arriving, so wasn’t expecting it to be quite as beautiful as it was described to me. Surprisingly, it actually far exceeded my expectations. I was specifically impressed by how dense the vegetation was, especially at such a high altitude. The forest consisted of deciduous and coniferous trees and a thick blanket of plants lining the forest floor. I had actually never seen a forest like that anywhere in China before, despite having traveled the country widely.

After exiting the boardwalk, we walked along a muddy dirt path down a small hill for a few minutes until we came to a small foot bridge that crossed a fast-moving river swollen with snowmelt from the surrounding mountains. From the other side of the river the trail started to lead upwards onto a heavily forested mountainside. The route was incredibly scenic but the trail soon became steep and muddy, making it a challenge both physically and in terms of simply trying to maintain balance and not slip in the mud. We stopped for short breaks every 30 minutes or so. After about an hour of hiking steadily uphill, we caught up with a large group of people and horses on the trail. There must have been at least half a dozen Tibetan guides and both a dozen horses and Chinese clients, half of whom were riding the horses. Since so many of the clients were on horseback, I assumed that they were just trekking in the mountains but I learned later on that they actually belonged to an expedition from another mountain guiding company that was also making its way to the same basecamp as us.

Looking down on the town of Rilong at the bottom of the valley from about 3700 metres above sea level, 500 metres higher than Riliong.

Looking down on the town of Rilong at the bottom of the valley from about 3700 metres above sea level, 500 metres higher than Riliong.

After 2 hours of hiking, we reached a stone cabin at 4000 metres above sea level, where we rested for about 30 minutes and had a snack. The cabin was staffed by a few local Tibetan men and stocked with instant noodles, cans of beer and non-alcoholic beverages like Red Bull, as well as bottled water. There we met another large group of people who were also on their way up to the same basecamp and a few people who had come down from the basecamp that day. The few who had come from basecamp told us they were unable to climb the mountain because it had rained so heavily the previous night that it prevented them from even leaving basecamp. This came as quite a shock as I hadn’t realized that rain could still fall at 4400 metres, even in June! The thought of having to also abort our climb due to rain was an unpleasant one that caused me a bit of worry but I tried not to focus on it.

This would either be a horse or yak skeleton; cows can’t survive at this altitude.

This would either be a horse or yak skeleton; cows can’t survive at this altitude.

Soon after leaving the cabin we hiked above the tree line, which offered spectacular views up and down the valley, but the views disappeared about an hour later when we reached the cloud line. From that point on, I was literally hiking with my “head in the clouds”. The last 450 metres of elevation gain was the most challenging part of the hike but we continued steadily upwards until we reached basecamp about an hour and a half after leaving the cabin.

A view of Rilong from above the treeline, about 4000 metres above sea level.

A view of Rilong from above the treeline, about 4000 metres above sea level.

A view of the mountains on the other side of the valley from just below the cloudline.

A view of the mountains on the other side of the valley from just below the cloudline.

Basecamp at 4476 metres above sea level.

Basecamp at 4476 metres above sea level.

Basecamp

(insert image of trek to basecamp)

I was pretty tired by the time we reached basecamp at about 2:30 pm. A sign at basecamp indicated that the elevation was 4476 metres, which meant that we had gained approximately 1300 metres in elevation during the 8 kilometre hike from the park entrance in Rilong to basecamp. It was quite a challenging hike even without a big backpack (I was only carrying a small backpack), but I felt like I could have gone a lot faster. The guides moved at a fairly slow pace and stopped for breaks more often than I thought was necessary, but I just assumed this was because most clients weren’t used to hiking at high altitude, so the guides didn’t want to push them too hard. For instance, despite being only 24 years old and talking about wanting to hike to K2 basecamp in Pakistan, the other client in our group really struggled with the hike and even had trouble keeping up with the slow pace of the guides. I had actually left him behind early on in the hike and ended up following some guides from another group that were far ahead of my own group. In hindsight though, it probably would have been wiser for me to have stuck with my own group and taken my time, since I developed a wicked headache from the altitude later that night, which I think possibly could have been avoided if I hadn’t hiked as fast as I did. It’s impossible to know if my pace caused the headache or not but it’s worth noting that the other guy in my group, who hiked much more slowly than I did, did not even get a headache, let alone a pounding one like I did.

The other guy in my group and I were met at basecamp by another client who had just finished climbing the “2nd Sister” that day. At 5276 metres above sea level, the summit of the 2nd Sister is only about 70 metres lower than the 3rd Sister but is considered quite a bit easier and doesn’t require ropes to reach the summit. He had hiked directly from the basecamp of the “2nd Sister” that day and was hoping to summit the “3rd Sister” with us the next morning. It turns out that he had actually climbed the “Eldest Sister” the day before as well, which meant that he was attempting to climb all three peaks in 3 days! I found out later that he was doing this as part of a training regimen to climb an 8163 metre high mountain in Nepal called Manaslu, which also happens to be the world’s 8th highest peak. I’m not sure if he was planning to climb it without oxygen but there are only fourteen peaks in the entire world with an elevation higher than 8000 metres (all are located in the Himalaya and Karakorum ranges of Asia) and they are all considered very difficult and dangerous to climb, so I was quite surprised to discover that a member of our small and humble expedition was planning to climb such a formidable mountain. He also told me later on that he had previously climbed two 6200 metre high peaks in China, which meant he already had some decent high altitude climbing experience under his belt. However, the leap from 6200 metres to 8163 metres is enormous, so it was very impressive indeed that he was planning to attempt to climb a mountain in the latter category.

The first thing I did on reaching basecamp was quickly set up my tent. I didn’t have a headache at that point but I was quite exhausted, so all I wanted to do was lie down and take a nap. Soon after crawling into my tent though, one of the guides told me not to fall asleep because we still had to undergo a brief training lesson on how to use ropes to climb the mountain safely. I had never used climbing rope before or any of the equipment associated with it, so one of the reasons I had chosen to try to climb this mountain was precisely because the guided trip I had joined included basic mountaineering training. The training turned out to be very basic actually, with our guides only teaching us two techniques: how to use an ascender device, also known as a Jumar, and how to rappel, or abseil. The guides each gave us a helmet and a safety harness with an ascender, a couple of carabiners and a rappelling device attached. Next they showed us how to put the safety harness on and explained what each of the devices and carabiners were for, then they tied a 50 metre length of rope to a large rock just above basecamp and showed us how to use the two devices and assorted carabiners.

The “ascender”, or Jumar, is a mechanical device that allows a climber to ascend a piece of rope without falling because it is designed to clamp to the rope when stationary and only move forward when in motion. Once the device is properly attached to the rope and secured with a carabiner, the climber simply has to slide it forward, then hold onto it and pull themselves forward until they are ready to slide it forward again. When the climber pulls on the device, their body weight creates enough friction between the rope and the device to prevent the device, and thus the climber, from slipping backwards down the rope. The guides showed us how to use the ascender and also how to safely detach it from the rope when reaching the end of a section of rope, then reattach it to a new section of rope and continue on.

The second technique they taught us was how to rappel, or abseil, which is used to descend a length of anchored rope safely. I won’t get into the details except to say that this technique also depends on creating friction on the rope to prevent the climber from falling by weaving the rope through a simple rappelling device (essentially two different sized rings welded together to form a lopsided figure 8). The genius of this technique is that when done properly, the climber can lower him or herself down a length of anchored rope very easily and at any speed they choose based on how much friction they apply between the rappelling device and the rope, which is simple to do.

Although the guides taught us only two fairly simple techniques, one for ascending a piece of rope and the other for descending it, this was all totally new to me, so I decided to practice for about an hour until I was comfortable with how everything worked. Safely and effectively implementing each technique required a number of steps that had to be done properly and in correct sequence in order to prevent accidents, which could prove fatal on a mountain, so I was pretty concerned with getting everything right! The guides even said that when it actually came time to use the ropes on the mountain, they would be at my side to monitor me each time I attached the devices to the ropes in case I made a mistake. They said such mistakes were common at high altitude because the lack of oxygen can cause a decrease in cognitive ability, ie, it can make you stupid!

After the training session we had a simple dinner consisting of instant noodles, a bit of bread and a boiled egg, which wasn’t much but I didn’t feel that hungry anyway. Then it started to rain. It rained lightly for about an hour before becoming torrential and continuing that way deep into the night, which made me worry quite a bit. I also started to develop a nasty headache from the altitude around 8 pm. I popped two ibuprofen but they didn’t start working until about 9, which is when I finally managed to fall asleep. Sleep proved fitful though, which is common at high altitude, and each time I awoke, I was all too aware of the rain pounding down on my tent. We were supposed to set off for the summit at 3 am, so by about midnight I was extremely worried that the rain wouldn’t stop before then. Fortunately, when I woke up at 1 am, the rain had subsided and had stopped completely by about 2, which was a great relief. I was also relieved to no longer have a headache.

Summit Day

Satelitte image showing the route we climbed from basecamp (bottom star) to the summit of the 3rd Sister.

Satelitte image showing the route we climbed from basecamp (bottom star) to the summit of the 3rd Sister.

After getting out of our tents at 2 am we spent the next hour getting dressed, putting on our gear, packing our bags and boiling water, which takes much longer at high altitude than sea level. We also ate a small breakfast consisting of a can of porridge each and some bread. I didn’t drink enough water the night before because it was raining too hard to boil water, so I drank about a litre of hot water at breakfast as well, then put another litre into my water bottle for the climb. I also put a 250 ml box of milk into my bag along with a couple of Snickers bars. We didn’t leave finally leave basecamp until about 3:30, which was half an hour later than planned so I was pretty eager to get moving.

Of course, it was still pitch dark when we set off, so we had to use our headlamps to navigate. I literally couldn’t see more than a few metres in any given direction for the first two hours, which was spent hiking gradually upwards along a narrow path over very rocky terrain. The path also meandered along some pretty steep cliff faces but it was so dark that we couldn’t tell how high on the cliff we were; anytime I looked down all I could see were a few metres of vertical rock and then complete darkness. I knew that falling meant being swallowed by the abyss but strangely, not being able to see the bottom was somewhat comforting and eased my fear. It wasn’t until I retraced my steps in daylight on the way back to basecamp later that morning that I could see the cliffs were both very steep and very high!

The first two hours were quite grueling, far more difficult than at any point during the hike from Rilong to basecamp the day before, but we didn’t actually reach the face of the mountain until about quarter to 6, just as the sun was rising. Unfortunately, I also developed another splitting headache about 30 minutes after leaving basecamp, which hurt far more than my headache the night before. I tried to tough it out for a while but a sharp shooting pain in one spot at the back of my head eventually got so bad that I decided to pop another 2 ibuprofen. For a while I worried I was developing serious altitude sickness and even considered turning back at one point, but decided to keep going. Thankfully, the ibuprofen eventually kicked in, which both eased my fears and made continuing tolerable.

When we left basecamp, there were only 3 climbing clients in my group, including myself, but after about an hour we caught up with the large group of guides and clients that we had seen hiking to basecamp the day before. They had camped at another campsite at basecamp about a 100 metres from ours and had set off for the summit at least 30 minutes before us that morning. It was surprising to see such a large group on their way to the summit though, not least because it included people who had rode on horseback to basecamp the day before. I assumed that since they had decided to ride horses to basecamp they must have been on some kind of overnight horse trekking tour that only went to basecamp; I didn’t expect that they would actually attempt to climb the mountain. When we finally caught up with this group, I could tell that most of them were really struggling, especially those who had ridden horses to basecamp the day before. I’m not sure if it was mainly because of the altitude, but I found the first two hours of hiking in the darkness quite exhausting as well and stopped frequently for short breaks.

After about 2 hours one of my guides turned to me and said that the hard part of the expedition was about to begin. It was still pitch dark, but high in the darkness in front of me I could clearly make out a line of lights stretching upwards into nothingness. It was a bewildering, almost disorienting site, like a slow moving elevator of lights to nowhere. It took me a few seconds to realize that it was in fact a group of climbers in front of us that had already begun to ascend the mountain face. Since it was so dark though, I couldn’t actually see the mountain or the climbers, so their headlights looked like a string of lights dangling in outer space. It was actually a pretty powerful sight to behold and it filled me with both a feeling of excitement and trepidation. I finally realized at that moment that there was a mountain in front of me and that the real climbing was about to begin. A few minutes later we walking in snow for the first time on the trip, so I knew the mountain face was very close.

On the Mountain

This satellite image shows the route we took from the base of the mountain face (red star) to the summit. The second arrow from the right indicates the col between the summit of the 3rd Sister (top left arrow) and the summit of the 2nd Sister (right arrow). The arrow between the col and the summit of the 3rd Sister is the point where we started using rope to climb the last 150 metres to the summit.

This satellite image shows the route we took from the base of the mountain face (red star) to the summit. The second arrow from the right indicates the col between the summit of the 3rd Sister (top left arrow) and the summit of the 2nd Sister (right arrow). The arrow between the col and the summit of the 3rd Sister is the point where we started using rope to climb the last 150 metres to the summit.

We started to ascend the actual face of the mountain in almost complete darkness at about 5:45 am. The slope was fairly steep, about 45 degrees, and covered in wet snow, but it wasn’t very difficult to climb; we simply placed our feet in the footprints left by the group in front of us, which felt like walking up a set of “snow stairs”. After only about 5 minutes of climbing, the darkness rapidly began to wane and I could finally see the mountain that we were climbing, which was a pretty amazing feeling!

This photo was taken at 5:50 am, just after climbing onto the face of the mountain and just as daylight began to break.

This photo was taken at 5:50 am, just after climbing onto the face of the mountain and just as daylight began to break.

This photo makes it appear that there was much more light than there actually was at the time; to the human eye it was in fact much darker, so we still had to use headlamps. A string of headlamps are visable in the top right corner of the photo.

This photo makes it appear that there was much more light than there actually was at the time; to the human eye it was in fact much darker, so we still had to use headlamps. A string of headlamps are visable in the top right corner of the photo.

This photo was taken right at the cloudline. It was an exhilarating feeling to actually be climbing above the clouds!

This photo was taken right at the cloudline. It was an exhilarating feeling to actually be climbing above the clouds!

This photo was taken a few hundred metres up the mountain face. A group of climbers are visable at the base of the mountain face.

This photo was taken a few hundred metres up the mountain face. A group of climbers are visable at the base of the mountain face.

The face of the mountain gradually steepened as we continued upwards at a decent pace. After a few hundred metres of climbing in snow we reached a section of rock that was quite a bit more difficult and dangerous to climb, as it was both slippery and jagged, so we had to be very careful with each step we took, since we were not attached to a rope. By that point the angle was well over 50 degrees and we had climbed several hundred metres in elevation. When I looked down all I could think about was how far the fall would be if anyone slipped. I was actually shocked that we weren’t expected to use rope on this section. I didn’t even have an ice axe and as far as I could tell, none of the other clients did either. Most had walking sticks, including myself, but they couldn’t be relied on to stop a fall if anyone lost their balance and went barreling down the mountain. Fortunately, everyone made it through the rocky section unscathed.

This photo shows the beginning of the rocky section.

This photo shows the beginning of the rocky section.

We continued up an increasingly steep snow slope, reaching about 60 degrees, for several hundred more metres until we were well above the clouds, which offered spectacular views of both the mountain we were climbing and others on the horizon. The views were so breathtaking that I actually became overwhelmed with emotion and started crying! It’s somewhat embarrassing to admit to having cried but I was so happy that I just couldn’t help it. Being where I was filled me with such a strong sense of euphoria that I cried tears of joy for several minutes as I was climbing (thankfully nobody noticed!).

This photo was taken just after the rocky section; the mountain face started to get quite a bit steeper from this point on.

This photo was taken just after the rocky section; the mountain face started to get quite a bit steeper from this point on.

Well above the clouds by this point, the views started getting quite spectacular.

Well above the clouds by this point, the views started getting quite spectacular.

Reaching the Col

(insert image of col to summit)

I was eventually able to make out the col of the summit from about 20 metres below it, although the summit itself was still out of sight (for those who don’t know, a col is the lowest part on a mountain ridge between two peaks). A short while later I reached the col, at an elevation of roughly 5000 metres, where at least 15 other climbers were already sitting in the snow. The view on the other side of the col was even more spectacular than anything I had seen up to that point. A sharply angled cornice of snow hung over the opposite side of the col with it’s underbelly basking in sunlight, while the side we were standing on was in shadow. The result of this visual contrast of light was profoundly beautiful. Adding to the beauty of the scene was a muted sun rising through the clouds that felt so close I thought I could almost touch it. A few climbers actually tried to get a better view over the other side of the col by stepping onto the snow cornice but when I saw them do this I shouted at them to stop and get back from the edge. They obviously didn’t know how much danger they were putting themselves in, otherwise they would have known that standing on a cornice, especially one that thin and angled, could have caused it to collapse and send them plummeting down the other side of the col, which would have spelled certain death. Sadly, many professional mountain climbers have met this fate.

Summit Push

It had taken me about an hour to reach the col from the foot of the mountain face, but despite the steepness of the climb I wasn’t feeling very tired. Our guides told everyone to take a short break before continuing upwards to the summit though as the climbing was going to get much more difficult. The climbers in front of me had already been at the col for about 15 minutes before I arrived but we all left together about two minutes later. Almost as soon as we left the col, I decided to push on in front of all the other climbers until I was following at the heels of the lead guide. I suppose I did this partly out of a feeling of competitiveness but the main reason was because I felt so energized by the sheer, stupendous beauty of my surroundings and the prospect of reaching the summit, which was finally beginning to feel like a very real possibility.

A few climbers can be seen at the col on lower left hand side of this photo.

A few climbers can be seen at the col on lower left hand side of this photo.

This was the lead guide. I stuck right behind him during the push from the col to the point where we roped up for the final summit push.

This was the lead guide. I stuck right behind him during the push from the col to the point where we roped up for the final summit push.

This section of the climb took us dangerously close to the edge of the mountain, which was a vertical drop of many hundreds of metres. Strong winds could have easily blown us over the edge and since we weren’t roped in, simply slipping could have meant sliding over the edge as well.

This section of the climb took us dangerously close to the edge of the mountain, which was a vertical drop of many hundreds of metres. Strong winds could have easily blown us over the edge and since we weren’t roped in, simply slipping could have meant sliding over the edge as well.

One of the guides carrying a 50 metre piece of rope.

One of the guides carrying a 50 metre piece of rope.

The climbing did indeed get quite a bit harder after leaving the col. The slope leading up to the summit gradually steepened to nearly 70 degrees and the weather deteriorated rapidly, with strong winds blowing up snow and heavy clouds decreasing visibility. Again, I couldn’t believe that we still weren’t using ropes, since falling on that slope could have easily proven fatal. I wasn’t even wearing the crampons I brought with me because the guides told me in Rilong that I wouldn’t need them. They said the snow on the mountain was wet enough that they wouldn’t be necessary but the snow on the slope leading to the summit from the col wasn’t wet at all, which made me regret having listened to them. I was also worried about how we were going to get down! For every ten metres or so that I climbed upwards, I couldn’t help but look back and wonder in amazement at how far I had come but also at how daunting it looked to climb back down.

Fortunately, the weather started to clear up quite quickly only about two hundred metres below the summit, which offered some truly spectacular views!

Me standing at the point where we roped up 150 metres below the summit.

Me standing at the point where we roped up 150 metres below the summit.

Roping Up

About 30 minutes after leaving the col, the lead guide and I were the first ones to reach the point where it was finally time to break out the ropes. We were only 150 metres from the summit, which I could finally see clearly. A few minutes later three more guides arrived, each carrying a 50 metre piece of rope. The next step was for these guides to climb up to the summit and anchor the 3 pieces of rope along the way, so that all the clients could use them to climb up to the summit safely. Of course, we had to wait while they did this, so the guides told us to use the time to rest, have a snack and drink some water. About 20 minutes later the first rope was secured and one of the guides told me that I could go first because I had been the first client to arrive at the spot where the rope climbing began. He watched me closely as I attached my ascender device to the rope and secured it with a carabineer, then told me I could go.

Here the lead guide can be seen climbing toward the summit with the first 50 metre piece of rope. After anchoring the first piece of rope, he climbed another 50 metres and anchored the second piece, before finally reaching the summit and anchoring the last piece. The summit can be seen clearly in this photo.

Here the lead guide can be seen climbing toward the summit with the first 50 metre piece of rope. After anchoring the first piece of rope, he climbed another 50 metres and anchored the second piece, before finally reaching the summit and anchoring the last piece. The summit can be seen clearly in this photo.

The first few metres on the rope were actually quite easy since I was now using rope to climb a snow slope that was no steeper than what I had just been climbing without a rope. The easy part abruptly ended though when the snow slope gave way to a much steeper rock face, which is when the climbing started to get very challenging. For some reason, I hadn’t expected climbing with a rope to require much upper body strength, which was a foolish oversight. When I started climbing up the rock face, I was immediately struck by how little upper body strength I had, especially in my arms. It was a struggle to pull myself up while holding the ascender with one arm and trying to use my other arm to maintain my balance. The conditions on the rock face, which steepened to over 70 degrees much of the way and almost 90 degrees in some parts, also made it difficult to get a foot hold, especially without crampons.

The rock face was steep, slippery and offered few places to get a solid foothold.

The rock face was steep, slippery and offered few places to get a solid foothold.

These guides were waiting for me at the point where the first 50 metre piece of rope ended and the second began. It was their responsibility to ensure that I unclipped from the first rope properly and attached myself to the second piece, which was crucial, since falling at this point would have been extremely hazardous. The summit is just 100 metres above.

These guides were waiting for me at the point where the first 50 metre piece of rope ended and the second began. It was their responsibility to ensure that I unclipped from the first rope properly and attached myself to the second piece, which was crucial, since falling at this point would have been extremely hazardous. The summit is just 100 metres above.

Here I’m literally hanging off the side of the mountain, secured only by a thin piece of rope attached to an anchor, while I switch from the second piece of rope to the final piece.

Here I’m literally hanging off the side of the mountain, secured only by a thin piece of rope attached to an anchor, while I switch from the second piece of rope to the final piece.

Strangely, I wasn’t very afraid to be hanging off the side of a mountain. It did cross my mind at the time that if the rope I was hanging from snapped or if the anchor it was attached to came loose or the ascending device and carabineer failed, well, that would be it, but this knowledge had little impact on my state of mind, although perhaps it should have. Actually, before undertaking this climb, I had also read that a young Chinese woman had died on the same mountain the year before because her rope anchor came loose while she was descending from the summit, but I was too focused on trying to reach the summit myself to let the thought of that get to me.

The first climber after me struggles to ascend the first piece of rope while a large group of guides and clients look on below.

The first climber after me struggles to ascend the first piece of rope while a large group of guides and clients look on below.

The closer I got to the summit, the steeper the rock face became; it was pretty much a sheer cliff at this point.

The closer I got to the summit, the steeper the rock face became; it was pretty much a sheer cliff at this point.

When I was about five metres from the summit, it finally dawned on me that I was going to make it, which filled me with a feeling of immense joy verging on eurphoria. The last few metres were really tough though, as they were practically vertical. Two guides were waiting for me about three metres below the summit and when I reached them, they told me to unhook my ascender device from the rope and sit down on a narrow ledge next to them.

Climbing the last few metres of rope.

Climbing the last few metres of rope.

The narrow ledge where I sat next to the guides after unhooking my ascender from the rope.

The narrow ledge where I sat next to the guides after unhooking my ascender from the rope.

The final rope anchor less than 2 metres from the summit.

The final rope anchor less than 2 metres from the summit.

Other climbing clients below me making their way up the last 50 metre section of rope.

Other climbing clients below me making their way up the last 50 metre section of rope.

I sat on the ledge for a few minutes admiring the view and taking photos until one of the guides suddenly told me to unhook the carabineer that connected my safety harness to the rope and follow him. I did as he instructed but the moment I unhooked from the rope, I was gripped with intense fear. The ledge we were standing on was about a third of a metre wide and covered with loose rock and snow. I knew that if I made one false move I would probably fall to my death, so I walked along the ledge very cautiously, as if my life depended on it, which it most certainly did! After walking horizontally along the ledge for a few metres, it narrowed even further and angled upwards, which meant we had to grip the rock face with both hands for added security. The guide was right in front of me the entire time directing me where to step but I was still extremely afraid of falling!

The ledge I walked along unroped to reach the summit. As it edges upwards it narrows until practically disappearing.

The ledge I walked along unroped to reach the summit. As it edges upwards it narrows until practically disappearing.

The Summit

After another nerve-racking few minutes of moving very slowly and with extreme caution, I arrived at the summit, which was not at all what I had expected. In all of the mountain climbing documentaries I had watched, the summits were always large enough to stand on but that was not the case with the 3rd Sister. Instead, it was a jagged, serrated edge, no more than half a metre wide! The best I could do was stand next to it and rest my arm on top of a thin piece of jagged rock; there was no way in the world I would ever dare to stand on it, nor would my guide ever allow me to do so.

The jagged 5355 metre high summit of Siguniang’s “3rd Sister”

The jagged 5355 metre high summit of Siguniang’s “3rd Sister”

The other side of the summit was a sheer cliff.

The other side of the summit was a sheer cliff.

Being right at the summit offered incredible views of surrounding peaks that couldn’t be seen from even 2 metres below the summit.

Being right at the summit offered incredible views of surrounding peaks that couldn’t be seen from even 2 metres below the summit.

It wasn’t until I was at the summit that I had my very first glimpse of the 4th Sister, the highest peak in the Siguniang range at 6250 metres. I honestly couldn’t believe my eyes for a moment when I first laid eyes on it. It looked as if it was floating in the clouds. Although it’s only 900 metres taller than the summit I was on, its giant snow covered pyramid towered massively above us. It was an absolutely stupendous sight. I have seen many impressive mountain peaks in my travels over the years, many of which are much higher than the 4th Sister, but no other peak I’ve ever seen compares with it. It looked like a white dagger stabbing the sky. As I was staring at it in astonishment, I just couldn’t believe that it had been climbed. It looked so lethal. Indeed, two Chinese climbers who had summited it the year before were killed by rockfall on descent; their bodies still lost somewhere on the mountain as I stood staring at it. As spectacular as my view of it was, I couldn’t help but get a bit overwhelmed by morbid thoughts. I had expected to feel happier to be at the summit but I was too afraid of my surroundings to really enjoy the view or take pride in my accomplishment at that moment. I knew I was the first client in a large group to reach the summit that day but it didn’t matter when I was standing on it; I just wanted to get down!

The view of the “4th Sister” from the summit of the “3rd Sister”.

The view of the “4th Sister” from the summit of the “3rd Sister”.

A close up shot of the “4th Sister” using a telephoto lens. An extrememly difficult and trecherous peak, only about 30 climbers have summited it since it was first successfully climbed in 1981 by a Japanese team.

A close up shot of the “4th Sister” using a telephoto lens. An extrememly difficult and trecherous peak, only about 30 climbers have summited it since it was first successfully climbed in 1981 by a Japanese team.

I quickly snapped a few photos and asked the guide to take a few of me standing at the summit, then told him that I wanted to get down. We retraced our steps slowly to the spot on the ledge where I had unroped but by that time the ledge was getting crowded with other climbers, which made me pretty nervous. I wanted to continue down the mountain right away but unfortunately the last 50 metre section of rope that I had used to climb to the ledge located 3 metres below the summit was now being used by other climbers to move along that ledge to the summit, i.e., the same route I had just traveled without a rope. The guide asked me if I wanted to descend the first 50 metre section of the mountain face without a rope. This was a tough question to answer though, not least because I knew that 80% of mountaineering accidents happen on descent.

This is the flag of the mountain guiding company I used to climb the “3rd Sister”.

This is the flag of the mountain guiding company I used to climb the “3rd Sister”.

The perilous route from the summit back down to the ledge where I had originally unclipped from the rope before climbing the last few metres to the summit unroped.

The perilous route from the summit back down to the ledge where I had originally unclipped from the rope before climbing the last few metres to the summit unroped.

A group climbers who had just finished climbing to the top of the rope wait on the ledge for their chance to go to the summit.

A group climbers who had just finished climbing to the top of the rope wait on the ledge for their chance to go to the summit.

The Descent

I sat on the ledge for a few minutes mulling over whether or not to descend the first 50 metres without a rope but then finally decided to go for it. My guide went first and directed me where to place my hands and feet but I was still completely terrified. Every step I took was made with extreme caution and focus. I knew there was no room for error whatsoever. The first 50 metres descending the mountain felt like an eternity and I was greatly relieved when I finally reached the first section of anchored rope.

My view from the ledge as I sat on it trying to decide whether I wanted to scale down this slippery snow covered and extrememly steep mountain face without a rope.

My view from the ledge as I sat on it trying to decide whether I wanted to scale down this slippery snow covered and extrememly steep mountain face without a rope.

Two other climbers about to descend the first 50 metres without a rope.

Two other climbers about to descend the first 50 metres without a rope.

Once I had rappelled to the end of the rope, I detached myself from it and started to walk down the mountain with my guide. The weather had deteriorated significantly by that point and I could barely see where I was going, so I had to stick close to my guide. Fortunately, the descent wasn’t as daunting as I had imagined it would be when I was on my way up.

This photo shows a climber rappeling down the last 50 metres of rope. By this time the weather had turned and the summit was no longer visable.

This photo shows a climber rappeling down the last 50 metres of rope. By this time the weather had turned and the summit was no longer visable.

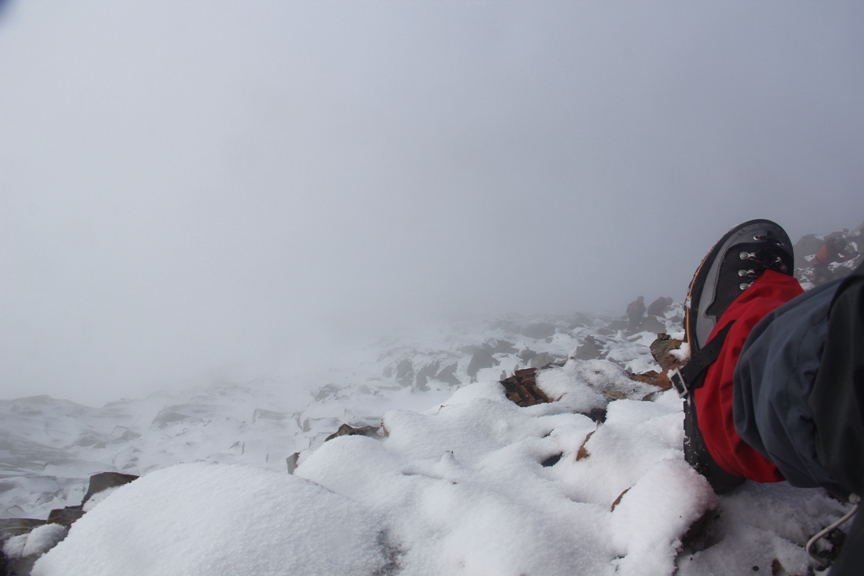

Visablity during the descent got progressively worse, to the point I could barely see more than a few metres in front of me.

Visablity during the descent got progressively worse, to the point I could barely see more than a few metres in front of me.

When I got back down to the col, the guide said to take a break and wait for some of the other climbers. A short while later the 25 year old Chinese guy from Inner Mongolia who I had shared a hotel room with arrived. We congratulated each other and high-fived and then he told me that he had almost quit the climb before reaching the col on the way up because he was so tired. At the time, he couldn’t see the col or the slope leading to the summit because of clouds but then the clouds cleared a bit and he saw that the col wasn’t far in front of him, so he decided to keep going. We continued down from the col together but he was having a much more difficult time descending the mountain than I was, so I had to help him quite a bit. At one point he lost his footing and actually went sliding down a steep slope at high speed for about 10 metres, before launching off a small patch of exposed rock and falling about 2 metres onto the slope below, where he continued to slide out of control for another 10 metres or so before coming to a halt. The guide that was accompanying us tried to run after him as soon as he started sliding but he was just going too fast. I could see that the guide was in a panic but all I could do was stand there and gawk in horror until the Chinese guy came to a halt. It was a very close call and I suspect that the only thing that saved him was wet snow; if it was dry snow or ice, he probably would have kept sliding for hundreds of metres, since he wasn’t roped in and didn’t even have an ice axe to try to execute self-arrest, which is a mountaineering technique for stopping precisely these kinds of falls. A few minutes later I had a small slip on some wet rocks in the same area and cracked my elbow on one of them, which hurt quite a bit but thankfully wasn’t serious. These incidents made me realize just how dangerous and unpredictable mountaineering really is though; no matter how careful you are, accidents can happen at any moment.

The 25 year old Chinese guy from Inner Mongolia struggling to descend the mountain face.

The 25 year old Chinese guy from Inner Mongolia struggling to descend the mountain face.

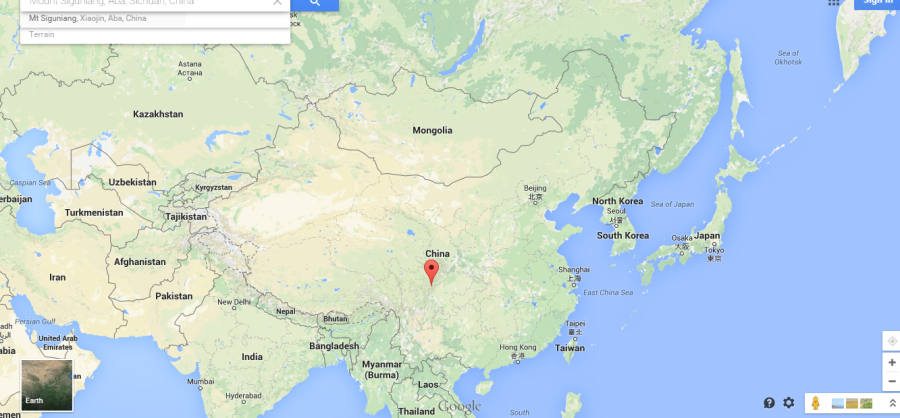

Descending this rocky section was quite scary, not least because there was almost zero visability!

Descending this rocky section was quite scary, not least because there was almost zero visability!

This is where the 25 year old Chinese guy that was descending with me slid down the mountain.

This is where the 25 year old Chinese guy that was descending with me slid down the mountain.

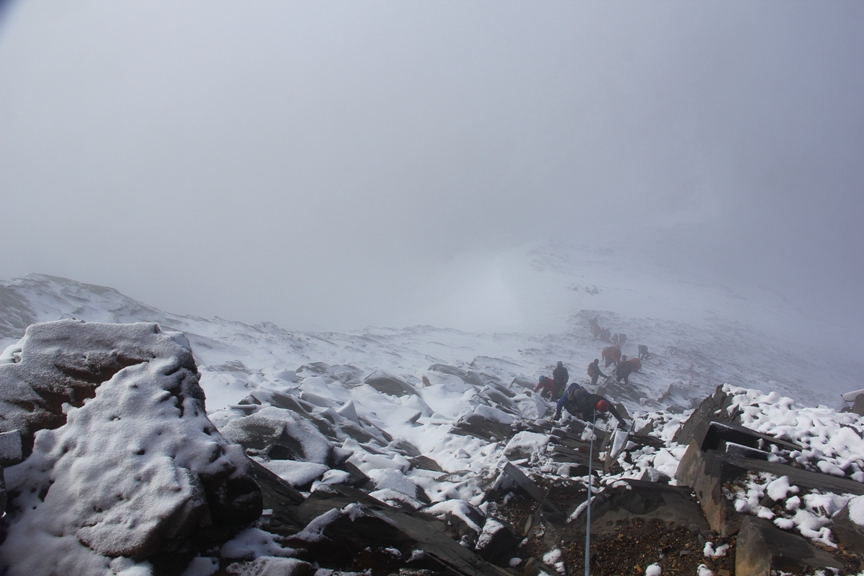

This photo shows a group of climbers just above the rocky section.

This photo shows a group of climbers just above the rocky section.

Descending the last few hundred metres before reaching the base of the mountain face.

Descending the last few hundred metres before reaching the base of the mountain face.

It was a relief to make it to the bottom of the mountain face unscathed but we still had 2 hours of hiking over rough terrain ahead of us before reaching basecamp and I was already very tired, hungry and thirsty. My headache had also returned with a vengeance. The Chinese guy I was with was completely wiped by that point but I didn’t want to wait for him, so I decided to go on ahead by myself while the guide stayed with him. I made it back to basecamp by myself at about 12:30 pm, about 9 hours after leaving it that morning. I was very much exhausted and starving by that point, so sat down and had a quick snack but I didn’t rest long because I still had to pack up and head back down to Rilong the same day.

Basecamp to Rilong

The hike from basecamp to Rilong took another 3 hours and was pretty hard on the knees but wasn’t nearly as exhausting as the journey from the summit back to basecamp. I actually quite enjoyed the hike back to Rilong and when I arrived at my hotel I wasn’t nearly as tired as I had expected to be. I was definitely very tired but I was expecting to feel “broken” and thankfully that wasn’t the case.

The entrance to Mount Siguniang National Park lies just ahead. Conveniently, there was a bus waiting there to ferry us to our hotel a few kilometres away.

The entrance to Mount Siguniang National Park lies just ahead. Conveniently, there was a bus waiting there to ferry us to our hotel a few kilometres away.

That night the Chinese guy who joined us at basecamp after having already climbed both the “Eldest Sister” and the “2nd Sister” invited me and the 25 year old Chinese guy from Inner Mongolia to have dinner with him and our guides. The dinner turned out to be a celebratory feast in typical Chinese fashion, which was very nice. We didn’t dine long though since everyone was ready to fall asleep in the restaurant after filling our bellies. We went back to the hotel at about 9 pm and promptly crashed, since we had woken up at 2 am that morning. Long day!

Reflections on Climbing the “3rd Sister”

Climbing the “3rd Sister” at Mount Siguniang National Park was without a doubt one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. In fact, the feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment far exceeded my expectations, as did the beauty of the scenery. I was also very impressed with the service and professionalism of my guides, especially for China! They really wanted everyone to succeed and were very friendly and courteous. I do have a few reservations about their safety judgment for letting me climb the last few metres to the summit without a rope and then descend the first 50 metres from the summit unroped as well, but I suppose I bear more responsibility for that decision, since I agreed to it (it wasn’t like they forced me)!

The most rewarding aspect of the experience was simply being able to overcome my own doubt and fear. I was in no way confident that I would succeed; on the contrary, there were several instances on the mountain when I thought I would have to throw in the towel. My first headache at basecamp made me worry that I wouldn’t be able to handle the altitude and the headache I got the next morning soon after leaving basecamp almost made me turn back. I had never climbed at that altitude before and didn’t know much about altitude sickness, so I actually panicked a bit when the second headache became quite severe; it wasn’t just a matter of enduring the pain, I actually feared that if I kept going I might die from altitude sickness. Fortunately, that fear was unfounded and I’ve since learned that it’s normal to get bad headaches and even vomit from high altitude; it’s only when vision becomes blurred and repeated vomiting occurs or breathing becomes difficult that a person should immediately retreat to lower altitude. The mental challenge far outweighed the physical though. Overcoming my doubts and fear was far more difficult than enduring the physical pain and exhaustion of the climb, which wasn’t insignificant either.

Even the hike from Rilong to basecamp was quite grueling. I’m glad I didn’t have to do it carrying a heavy backpack because I would have been a wreck by the time I reached basecamp; I may not have even had the energy to reach the summit the next morning. This is speculation, of course, but it’s worth noting that proper physical conditioning and endurance is definitely a prerequisite for mountain climbing! One problem I have in this regard is a tendency to push myself beyond my physical limits, which can be quite dangerous. There have been many cases where mountain climbers push themselves too hard then simply drop dead from exhaustion right on the summit. There’s no point making it to the summit without making it back down alive though, so you have to properly gauge how far you can push yourself without getting to the point of no return, which can be difficult. From what I’ve read, many mountain climbers get so fixated on reaching the summit that they throw caution to the wind; it’s almost as if they don’t care if they live or die, as long as they reach the summit. Mountain climbing can cause a kind of mania and it’s definitely addictive! I felt this when I was climbing the 3rd Sister. All I wanted to do was get to the top. Fortunately, the climb wasn’t physically demanding enough to cause me to push myself to the point of complete exhaustion, but I’m worried that if I ever climb a harder mountain, which I definitely plan on doing someday, I may indeed push myself to that point.

I learned from one of the guides after the climb that there were 18 climbers (not including guides) who attempted to climb the 3rd Sister that day but four turned back before reaching the summit. I’m proud to say that I was the first climber among them to reach the summit, not least because it was my first time really climbing a mountain (as opposed to merely scrambling up one in Kyrgyzstan, which didn’t really count as mountain climbing), but also because there was a large group of climbers far in front of me for half of the climb who I still managed to catch up with and pass. It wasn’t supposed to be a race, of course, but it felt good nonetheless to be the first to the top that day. At 5355 metres, it was also a pretty challenging mountain for a first time climber. All novice mountaineers who have climbed the 3rd Sister should be proud; it’s both a physical and mental accomplishment. For anyone who is interested in learning to become a mountaineer, the 3rd Sister is an exciting and challenging choice. It’s also relatively convenient and inexpensive to climb. Mount Siguniang National Park is also a spectacularly beautiful place to climb a mountain.