Tip of red arrow on the map above marks location of the Kulma Pass.

Clutching my passport with a sweaty palm, my heart raced as I rode along a bumpy, unpaved road in an old Mitsubishi SUV high up on the Pamir plateau in a remote corner of Tajikistan. I was heading towards the Chinese border with the intention of crossing the Kulma Pass, the only official border crossing between Tajikistan and China. It was mid-November and I had just hired the SUV, with driver, a few hours earlier at a bazaar in a depressingly desolate and dusty town called Murghab, located about 90 km from the pass.

Arriving in Murghab the night before from Kyrgyzstan via the legendary M41 Pamir Highway, I was excited about the prospect of crossing the Kulma Pass but also very nervous, since I didn’t know if it was open, or if foreigners were even allowed to cross it.

I had traveled a long way to get to that point and if I failed to get across, I would have had to go all the way back to Kyrgyzstan. I left the capital of Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, 3 and half days before and travelled more than 1200 km by land through the heart of Central Asia for the sole purpose of walking across the Kulma Pass. I wanted to cross the Kulma very badly.

As a self-professed “border junkie”, the Kulma Pass represented the “Holy Grail” of border crossings for me. At an elevation of 4365 metres above sea-level, the Kulma is not only a remote border post, it also happens to be the second highest international border crossing in the world, linking Tajikistan’s rugged and mountainous Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) region with the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), China’s largest provincial level political unit (Xinjiang is often referred to as a “province” of China but this is technically incorrect; like Tibet, it is actually an “autonomous region”).

I had made the decision to attempt to cross the Kulma Pass from Tajikistan into China a few days earlier while in Bishkek. I was at my hostel thinking about how to travel from Kyrgyzstan to China by land when I read on a travel website called Carivanistan.com that Tajikistan had recently begun issuing e-visas to foreign tourists. This was exciting news because it opened the possibility of traveling from Kyrgyzstan to Tajikistan on short notice and then entering China via the Kulma Pass. There was one major problem though: at that time, I didn’t actually know if Canadian citizens were even allowed to cross the Kulma Pass. I had long wanted to cross this pass and thought about attempting to do so while traveling through Tajikistan a few years earlier, but from all the information I could gather at the time (online and in person), it appeared that the Kulma Pass was closed to non-Tajik or Chinese citizens, i.e.”third country nationals” (for reasons unbeknownst to me).

A few years had passed since then, so I decided to do a little research online to see if I could find any reports of “third country nationals” (“TCNs”) having crossed the Kulma in recent years. Fortunately, I did find a report on Caravanistan of a US citizen claiming to have crossed, with difficulty, a few months previously. The Kulma Pass border crossing first opened in late 2004 but was officially restricted to Chinese and Tajik nationals until sometime in 2013 or 2014, when the rules suddenly changed to supposedly allow TCNs (ie, non-Chinese or Tajik citizens) to cross as well. The first online report of a TCN crossing the Kulma was by a Chinese guy from Hong Kong with a British passport who reported having crossed the Kulma from China into Tajikistan in mid-2014. The next year, a TCN of undisclosed nationality and gender reported crossing the Kulma from China into Tajikistan as well, but said he/she had to “battle” with Chinese bureaucracy for 6 days before border officials on the Chinese side reluctantly allowed he/she to cross. I could only find these three online reports, for a grand total of three TCNs crossing the Kulma since 2014. Unfortunately, I also read plenty of other online reports of failed attempts by TCNs since 2014, but I figured if at least one TCN had been successful recently, there was at least a glimmer of hope for me too. I also figured I had a few advantages going for me over the average traveler, namely: being a resident of China with a work permit and being able to speak Chinese, both of which turned out to be vital to my success.

Armed with this confidence, I immediately applied for a Tajik e-visa online from the comfort of my hostel in Bishkek and received it an hour later (so much easier than applying at the embassy)! Two days later I paid for a seat in a cramped private car and traveled 650 kilometres from Bishkek along the M41 Pamir Highway to Kyrgyzstan’s second largest city, Osh, in one day. I had to travel in a private car because, somewhat inexplicably, there is no public bus or train service between Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, and Osh, its second largest city!

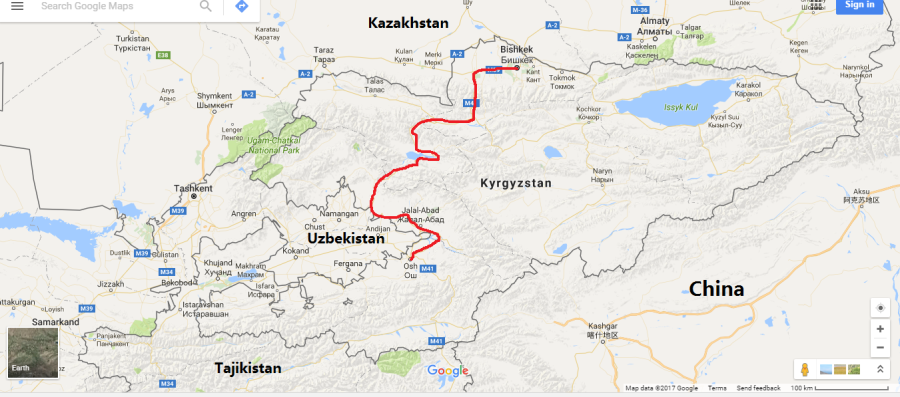

Red line shows route from Bishkek to Osh on the M41 Pamir Highway (the actual M41 technically starts in Kara-Balta, 62 km west of Bishkek).

Red line shows route from Bishkek to Osh on the M41 Pamir Highway (the actual M41 technically starts in Kara-Balta, 62 km west of Bishkek).

Scenery during the drive from Bishkek to Osh along the M41 Pamir Highway. Dubbed the “Heroin Highway” because of its importance as a conduit for smuggling Afghan opiates through Central Asia and into Russia and China, the M41 is a transnational highway running through the heart of Central Asia, connecting Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Scenery during the drive from Bishkek to Osh along the M41 Pamir Highway. Dubbed the “Heroin Highway” because of its importance as a conduit for smuggling Afghan opiates through Central Asia and into Russia and China, the M41 is a transnational highway running through the heart of Central Asia, connecting Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

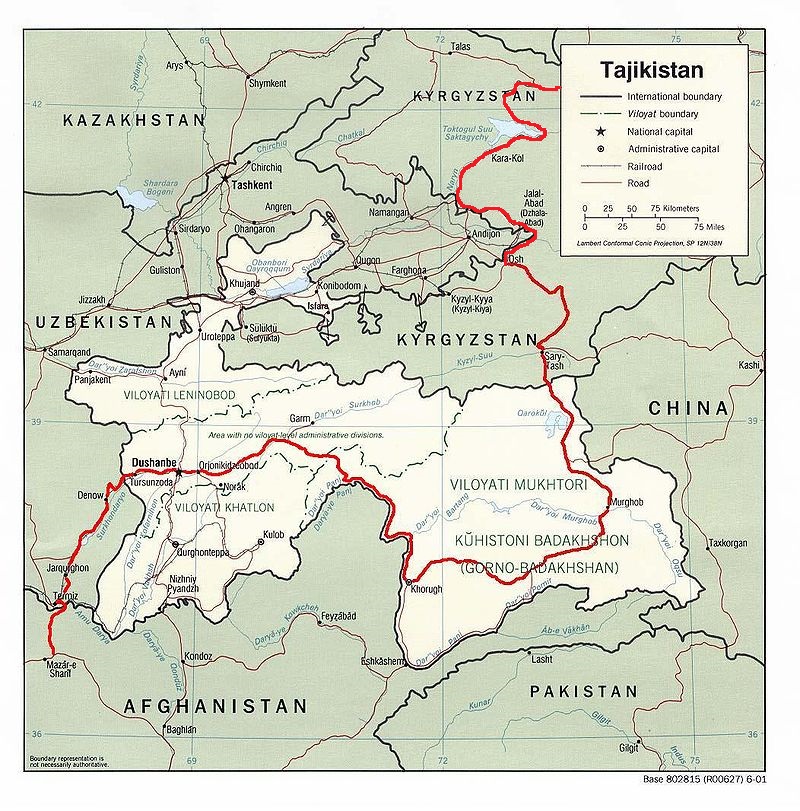

The above map shows the full extent of the modern M41 Pamir Highway, from Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan on the lower left of the map, all the way to Kara-Balta in Kyrgyzstan, just outside of Bishkek. Note that most of the highway runs through Tajikistan. Its name derives from the fact that it traverses the Pamir Mountains, which lie mostly within Tajikistan. Contruction of the highway began in the 19th century and was completed by the Soviet militarty in the 1930’s, which was considered a major feat at the time due to the harsh, mountainous terrain it was carved through. The Pamir Highway is considered one of the most dangerous and scenic highways in Asia, if not the entire world. It’s also the second highest international highway in the world, after the Karakorum Highway, which runs from far western China’s Xinjiang “province” to Pakistan.

I spent the night at a hostel in Osh, which is located in southwestern Kyrgyzstan, right on the border with Uzbekistan, then travelled 215 km by bus the next day to a tiny village in the far south of Kyrgyzstan called Sary Mogol. Located in the beautiful Alay Valley, 30 km from the Tajik border, Sary Mogol is the setting off point for visiting and/or climbing Peak Lenin, which straddles the Kyrgyz-Tajik border and, at 7135 metres, is one of the highest mountains in both countries.

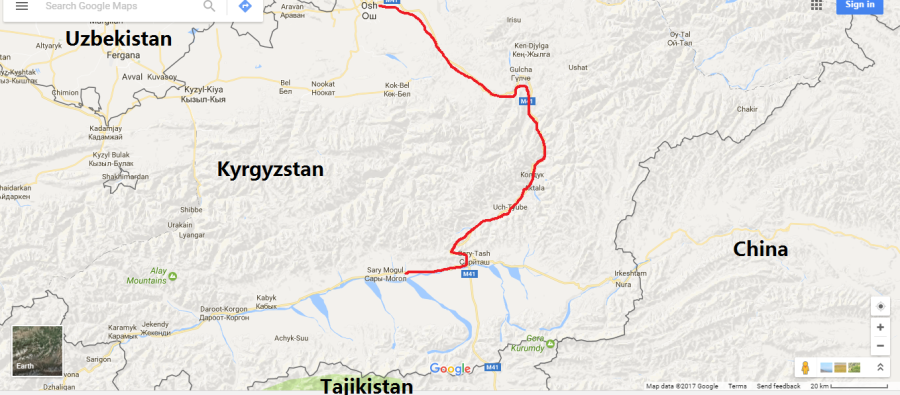

Red line shows route from Osh to Sary Mogol.

Red line shows route from Osh to Sary Mogol.

Scenery during the drive from Osh to Sary Mogol.

Scenery during the drive from Osh to Sary Mogol.

Sary Mogol in the morning. 7135 metre high Peak Lenin is faintly visible in the background of the above photo.

Sary Mogol in the morning. 7135 metre high Peak Lenin is faintly visible in the background of the above photo.

After spending a night in Sary Mogol, I hitchhiked the next morning to another tiny village nearby called Sary Tash, which is located right at the crossroads of the M41 Pamir Highway and another highway that heads east to the Irkeshtam border crossing with China 70 km away. From Sary Tash, the M41 Pamir Highway continues south to the Kyzyl Art Pass border crossing with Tajikistan 45 km away. Back in Osh I had already pre-arranged and paid a deposit for a seat in a jam-packed Toyota Landcruiser SUV (every seat had a passenger and the back and roof were full of cargo) to take me from Sary Tash to a small town in Tajikistan called Murghab. The entire route was along the M41 Pamir Highway and took us over the 4280 metre high Kyzyl Art Pass, which happens to be the third highest international border crossing in the world, just behind the Kulma Pass (4365 m). The 230 km journey from Sary Tash to Murghab took about 10 hours because the road was in terrible condition. It’s worth mentioning that the M41 Pamir Highway deteriorates badly just outside of Sary Tash and is largely rough gravel on the Tajik side of the border, so is really only safely travelled by SUV. In fact, there is no public bus service between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, largely for this reason, but also because there is so little traffic of any kind passing between the two countries over the Kyzyl Art Pass; during the entire 10 hour journey we passed just one other vehicle – an old Soviet era ambulance in Tajikistan crammed with passengers.

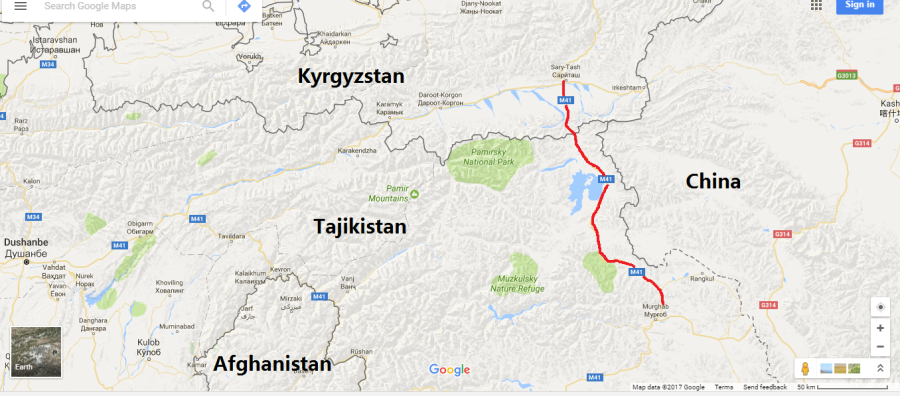

Red line shows route from Sary Tash to Murghab.

Red line shows route from Sary Tash to Murghab.

Sary Tash and the M41 Pamir Highway.

Sary Tash and the M41 Pamir Highway.

Border post on the Kyrgyz side of the 4280 metre high Kyzyl Art Pass. Note the Kyrgyz flag.

Border post on the Kyrgyz side of the 4280 metre high Kyzyl Art Pass. Note the Kyrgyz flag.

No man’s land in the Kyzyl Art Pass, just after passing through the Kyrgyz border post. There is about 25 km of no man’s land between the Kyrgyz and Tajik border posts.

No man’s land in the Kyzyl Art Pass, just after passing through the Kyrgyz border post. There is about 25 km of no man’s land between the Kyrgyz and Tajik border posts.

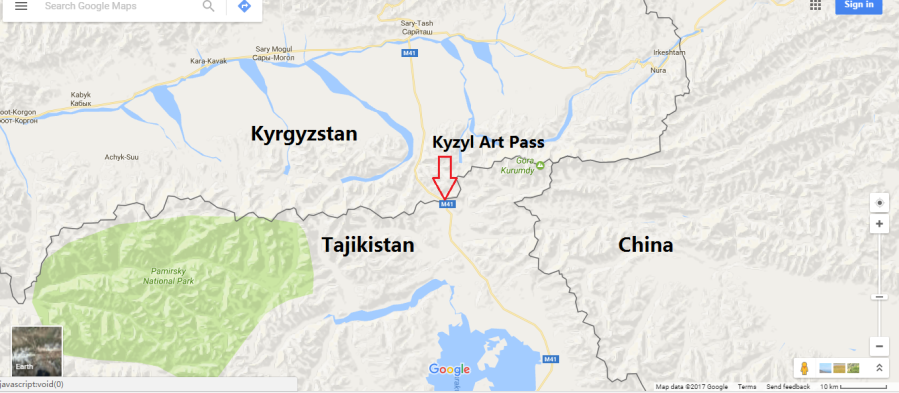

Location of the Kyzyl Art Pass on the map. Note how close it is to the Sino-Tajik border (less than 20 km).

Location of the Kyzyl Art Pass on the map. Note how close it is to the Sino-Tajik border (less than 20 km).

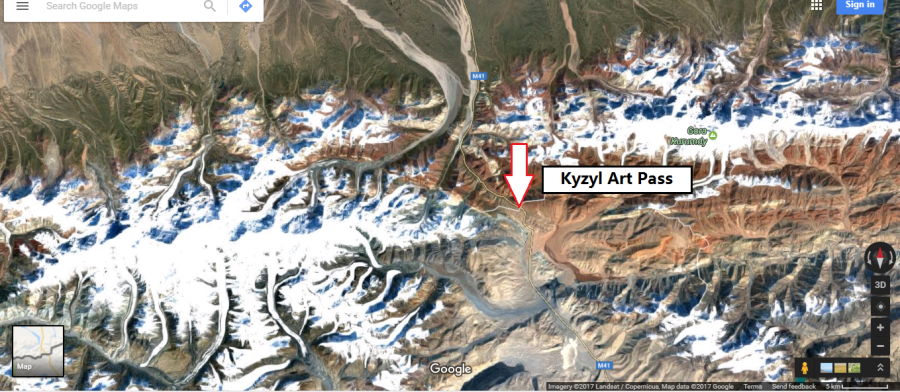

Satellite imagery of the Kyzyl Art Pass. Note how it cuts through the snow capped mountain range that forms the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Satellite imagery of the Kyzyl Art Pass. Note how it cuts through the snow capped mountain range that forms the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Landcruiser and driver in the Kyzyl Art Pass.

Landcruiser and driver in the Kyzyl Art Pass.

Climbing to the top of the Kyzyl Art Pass just before the Tajik border post. Note that the section of the M41 Pamir “Highway” that crosses this pass is actually a single lane gravel jeep track.

Climbing to the top of the Kyzyl Art Pass just before the Tajik border post. Note that the section of the M41 Pamir “Highway” that crosses this pass is actually a single lane gravel jeep track.

Standing at the Tajik border post with a sign behind welcoming visitors to the Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous (GBAO) Region of Tajikistan.

Standing at the Tajik border post with a sign behind welcoming visitors to the Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous (GBAO) Region of Tajikistan.

This photo shows a long border fence between China and Tajikistan running right next to the M41 Pamir Highway. Built by the Chinese, it actually lies about 10-20 km within Tajik territory, probably because it wasn’t possible to build a fence right on the actually Sino-Tajik border. There is a dirt jeep track on the Chinese side of the fence used for patrols by Chinese border defence guards.

This photo shows a long border fence between China and Tajikistan running right next to the M41 Pamir Highway. Built by the Chinese, it actually lies about 10-20 km within Tajik territory, probably because it wasn’t possible to build a fence right on the actually Sino-Tajik border. There is a dirt jeep track on the Chinese side of the fence used for patrols by Chinese border defence guards.

We stopped for lunch in a tiny, desolate village called Karakul, which lies right on the eastern shore of 3960 metre high Lake Karakul, one of the highest actual lakes in the world (as opposed to high altitude pools, which are sometimes described as lakes). Created by an impact crater, it is a very deep (230 m) endorheic lake, which means it lacks drainage and causes it to be slightly saline. With a surface area of 380 square km, it is significantlly smaller but higher than Lake Titicaca (8,372 square km/ 3,812 m), which is often erroneously referred to as the “highest lake in the world”.

We stopped for lunch in a tiny, desolate village called Karakul, which lies right on the eastern shore of 3960 metre high Lake Karakul, one of the highest actual lakes in the world (as opposed to high altitude pools, which are sometimes described as lakes). Created by an impact crater, it is a very deep (230 m) endorheic lake, which means it lacks drainage and causes it to be slightly saline. With a surface area of 380 square km, it is significantlly smaller but higher than Lake Titicaca (8,372 square km/ 3,812 m), which is often erroneously referred to as the “highest lake in the world”.

Location of Karakul Lake on the map.

Location of Karakul Lake on the map.

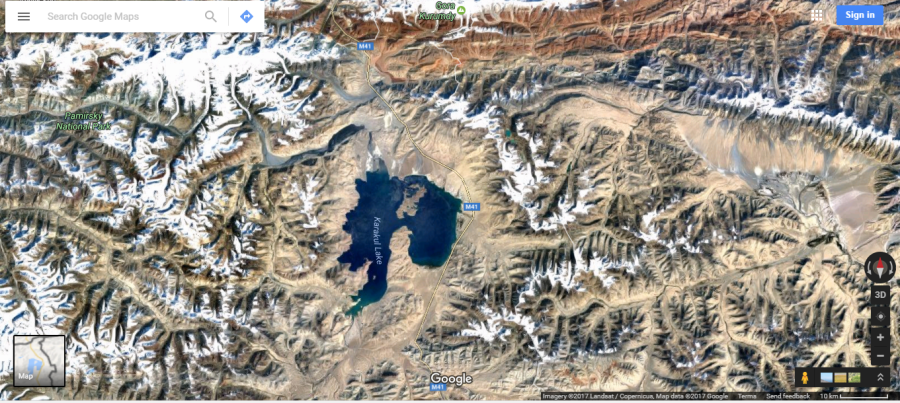

Satellite imagery of Karakul Lake surrounded by the Pamir mountains. Note how mountainous the surrounding area is.

Satellite imagery of Karakul Lake surrounded by the Pamir mountains. Note how mountainous the surrounding area is.

I found this ibex skull with horns on the shore of the lake.

I found this ibex skull with horns on the shore of the lake.

This old Soviet era ambulance was the only other vehicle we saw during the 10 hour journey from Sary Tash to Murghab; it was crammed with passengers.

This old Soviet era ambulance was the only other vehicle we saw during the 10 hour journey from Sary Tash to Murghab; it was crammed with passengers.

Moonscape scenery on the way to Murghab.

Moonscape scenery on the way to Murghab.

Once in Murghab, I bedded down for the night in a guesthouse and woke up early the next morning and walked down to the local bazaar to look for a ride to the Kulma Pass, 90 km away. I was hoping to hitch a ride on a transport truck going to the pass but didn’t see any at the bazaar, nor did I see any passing through Murghab on the road leading to the pass. My second choice was to pay for a seat in an SUV the way I did from Sary Tash to Murghab the day before but I wasn’t having any luck with that either.

Red line shows route from Murghab to the Kulma Pass

Red line shows route from Murghab to the Kulma Pass

After waiting around the bazaar for a few hours, I ended up hiring an SUV, as a taxi of sorts, to drive me from Murghab to the Kulma Pass because there were no transport trucks or shared vehicles heading that way on the morning I wanted to go. Murghab is a sullen and drab, treeless town with a brutally barren, lunar landscape, so I wanted to get out of there as soon as possible. Located in an isolated, windswept region of Tajikistan on the Pamir plateau at an elevation 3650 metres, Murghab was established as a strategic military outpost by the Soviet Army in the 1930s because of its proximity to the Chinese frontier, Afghanistan and British India. Today Murghab represents an environmental catastrophe. The landscape surrounding it, basically a high altitude desert, has never been capable of supporting anywhere near the 4000 souls who have the misfortune to reside there. Despite this, Murghab survives as a transport hub because it lies at a junction of the M41 Pamir Highway, a lifeline for Tajikistan’s remote GBAO region, and a shorter highway that leads to China over the Kulma Pass.

The ride from Murghab to the Kulma Pass cost me $55 USD, which was a bit pricey for 90 km, but the driver said he wouldn’t be able to find any other passengers to go with me, nor be able to find any on the way back, so I was essentially renting the whole vehicle to myself as a round trip, whether I wanted that or not (I didn’t). Of course, the silver lining to this was that I would have been able to ride back with him if I was turned away by Tajik border guards, which was a definite possibility. The driver seemed a bit worried about this, as well. He told me he had been to the Kulma Pass many times but had never seen or heard of a TCN crossing it. When he asked if I had a Chinese visa, I said that I actually I lived in China and showed him my work permit, then he said “Oh, ok, no problem”!

Beautiful Murghab

Beautiful Murghab

Looking for a jeep at the Murghab bazaar to take me to the Kulma Pass.

Looking for a jeep at the Murghab bazaar to take me to the Kulma Pass.

The 90km drive from Murghab to the Kulma Pass took about 3 hours because most of the road was abominably bad – by far the worst road I’ve travelled on in Central Asia (not counting Afghanistan). The road was in a dire state of disrepair for the first 70km – unpaved, badly potholed and pock-marked – but the last 20km was paved and in decent condition. It was evident that large tractor-trailer transport trucks plying the cross border trade between Tajikistan and China over the Kulma Pass had basically thrashed the unpaved portion of the road to smithereens. About an hour into the journey we passed a convoy of two such trucks lumbering along uneasily at about 20km per hour. Despite the altitude (about 3700 metres, at that point) and season (mid-November), there was no snow, but the road was so decrepit that the trucks couldn’t manage to go any faster. Even at 20km per hour, I could see that their suspension systems were taking a beating, as was the road under the weight of their loads; I didn’t know whether or not to feel more pity for the trucks or the road.

Crossing a dilapitated bridge on the road from Murghab to the Kulma Pass.

Crossing a dilapitated bridge on the road from Murghab to the Kulma Pass.

Moonscape scenery on way to the pass.

Moonscape scenery on way to the pass.

I think we passed one or two tiny settlements along the way – not villages or even hamlets, but bleak little herding outposts in the middle of nowhere. Apart from the two transport trucks, the only other vehicle we saw was a camo-painted Humvee that drove by us shortly after we began driving on the newly paved section of the road. A short while later, we came to a military checkpoint manned by two Tajik soldiers. One of them stood in front of a fence that blocked the road and signaled for us to stop as we approached. We got out of the vehicle and he directed us into a hut at the side of the road where another soldier inside greeted us politely and asked to see our IDs. I nervously held my breath as he inspected my passport, fearing that he was about to turn us back, but relaxed once he began to write my information in a log book. Once we emerged from the hut, the soldier outside opened the gate for us and we continued on our way.

The road finally improved 20km before reaching the Kulma Pass.

The road finally improved 20km before reaching the Kulma Pass.

The topography quickly changed from lunar “doom-scape” to gently rolling hills and it soon became obvious that we were gaining elevation rapidly. About 10 minutes past the military checkpoint we saw a road sign indicating that the Kulma Pass was a mere 10 km away! As soon as I saw it, my pulse quickened, both out of nervousness and excitement. The surrounding hills began to close in as we approached the top of the pass, then all of a sudden, a massive, snow and ice-encrusted mountain came into view. I quickly realized this was Muztagh Ata, which means “Father of Ice” in Turkic because of the large number glaciers spilling out of it. One of the most famous mountains in Xinjiang, the Chinese province or “autonomous region” that borders Tajikistan, I’d seen it up close several times before while traveling in Xinjiang, so I knew what it looked like. On cresting a hill, I could finally see the Tajik border post about 5 km in front of us. Consisting of several sizeable, squat 2 and 3 story buildings, the border post was much larger than I expected for being in such a remote area.

10 km to go.

10 km to go.

The scenery at the top of the pass, with the enormous Muztagh Ata massif towering over the border post, was absolutely stunning. Despite being located about 30 kilometres from the border on the Chinese side, Muztagh Ata is so enormous in both height (7500 metres) and circumference that it looked as if the border post was located right at the base of it. At an elevation of 4365 metres above sea level, the Kulma Pass is the second highest international border crossing in the world after the 4693 metre high Khunjerab Pass, which lies on the fabled Karakorum Highway (referred to in China as the “Sino-Pakistan Friendship Highway”) that runs from Kashgar, in Xinjiang, to Islamabad. The Kulma Pass is also the only official border crossing between Tajikistan and China, while the Khujerab Pass is likewise the only official border crossing between China and Pakistan (I’ve crossed this twice before). Both passes, which are only about 200 km apart by road (150 km as the crow flies), are located in remote, sparsely populated areas that offer superb high-altitude mountain scenery. It’s tough to decide which pass offers better scenery but if I had to choose, I’d say the Kulma wins out because of the presence of Muztagh Ata, which totally dominates its surroundings. Fortunately, the weather was also excellent that day – cold and windy, to be sure, but sunny and clear.

A few kilometres from the pass with Muztagh Ata towering above.

A few kilometres from the pass with Muztagh Ata towering above.

As we came within a few kilometers of the border crossing, I was relieved to see a long line of transport trucks parked on the Tajik side. There must have been at least 50 trucks waiting at the border, which was a good sign for two reasons: first, it indicated the likelihood that the border was indeed open, and secondly, it meant the possibility of hitching a ride from the top of the pass, where the official border crossing is, to the Karakorum Highway 14 km away at the bottom of the pass on the Chinese side. I was still pessimistic about my chances of even getting across, but at least it looked like I would have an opportunity to plead my case and, if successful, possibly even avoid having to walk 14 kilometres in cold weather . I read conflicting information online about when the pass was actually open to traffic; Wikipedia said it was open from the 16th to the 30th of the month from May to November (I was trying to cross on November 15th) but other sites like Caravanistan said it was open all month and “closed in winter until late April/early May”, but didn’t mention when it actually closed for the winter.

When we pulled up to the Tajik border post, there was an armed Tajik soldier standing in front of a gate blocking the road. We stopped just before the gate and my driver got out of the jeep to speak to him. After about a minute the soldier signaled to me to get out as well, so I grabbed my belongings and showed him my passport. He inspected it half-heartedly, then opened the gate and signaled to me without speaking to follow him. At that point, I looked back and saw my driver and his father (who had come along for the ride), standing beside their jeep. They looked a bit nervous, which made me even more nervous, but I was also relieved to see they hadn’t already driven away. I’m guessing they wanted to see if I was going to be allowed through.

I followed the soldier towards a building on the opposite side of the road but as we were crossing it, a Chinese SUV with Chinese military license plates pulled up right beside us and stopped. I could see several uniformed Chinese soldiers inside, as well as a Tajik man in civilian clothes sitting amongst them. It was obvious right away that the Tajik man, much more so that the Chinese soldiers, was surprised by my presence. He immediately demanded in excellent English to see my passport. After quickly inspected it, he started questioning me in a polite but moderately stern and suspicious tone. He asked how I had arrived at the Kulma Pass and where I was going. I told him I had hired a private jeep in Murghab to drive me to the border and that I wanted to enter China via the Kulma Pass, but he seemed unsatisfied with my answers and continued with more questions, namely when and how I had entered Tajikistan. I told him I had crossed from Kyrgyzstan into Tajikistan over the Kyzl Art Pass by shared jeep the day before, then spent the night in Murghab before hiring a jeep in the morning. He inspected my passport again to see if my story checked out before dropping the bomb that I had feared all along: the Kulma Pass was not open to non-Chinese foreigners. My heart sank on hearing these dreaded words, but I quickly replied that I lived in China with my Chinese wife and daughter and had a work permit, which I took out to show him as well. To my surprise, as soon as I mentioned this, he switched to Chinese, which he spoke fluently. I immediately replied in kind, which seemed to impress both him and the Chinese soldiers in the jeep. As soon as we switched to Chinese, the whole tone of the conversation changed from that of an interrogation to friendly chitchat. My Tajik interrogator even joked with me about how lucky I was to have a Chinese wife, while the Chinese soldiers began to ask me the standard, boring questions that Chinese people always ask me about my life in China: how long I’ve lived there, what do I do, am I used to Chinese food, etc. After a few minutes of this, the Tajik man got on his radio and began speaking in Tajik. After about a minute on the radio, he suddenly asked me for my “immigration card”. Unsure what he was referring to, I reluctantly told him I didn’t have one and didn’t even know what that was. He was obviously a bit annoyed by my answer and asked if a border guard at the Kyzyl Art Pass who had stamped my passport the day before had not given me one. I told him that I hadn’t received one when I entered Tajikistan, which was the truth, but he said I should have. A moment of tense silence passed, in which he appeared to be thinking about what to do about the absent “immigration card”, then he suddenly addressed the Tajik soldier who was with me and started speaking to him in Tajik. The solider listened intently and nodded eagerly the way soldiers do when receiving orders from a superior. When he finished speaking to the solider, he handed back my passport and work permit and told me that the soldier would escort me to the customs and immigration building. A dizzying feeling of euphoric relief washed over me at that moment! I smiled widely and immediately reached into the car with my hand outstretched to shake his, which he accepted, then thanked him several times in Chinese, English, Tajik and Russian as we shook hands.

After saying goodbye to everyone in the jeep, I turned around to see if my driver was still waiting. He was, so I smiled and waved to him as a gesture of thanks before pointing towards China to indicate that I was heading in that direction. He smiled and waved back, then I turned around and walked towards the customs and immigration building with my military escort. Once inside, he pointed me to a window with another soldier behind it who beckoned me to hand over my passport, while also asking in Russian if I spoke Russian, to which I replied “nyet”. I was the only traveler in the room. As the soldier behind the window inspected my passport, the soldier who escorted me to the building used pantomime to tell me to take off my backpack and remove its contents. He made a cursory, half-hearted inspection of the contents as I removed them piece by piece but before I was half finished, he signaled me to pack my bag. Afterwards, we stood in awkward silence for a few more minutes until the solider behind the window handed back my passport. I immediately flipped through the pages to look for the Tajik exit stamp; sure enough, it was there! I smiled and thanked him in Russian and Tajik, then the soldier who escorted me to the building walked me outside and pointed towards the Chinese border post about 300 metres away. I thanked him in Tajik and Russian as well, then turned around and began walking along the road towards Chinese territory.

I was slightly surprised that the soldier just let me walk away unescorted in a restricted border zone but maybe he wasn’t allowed to go any closer to Chinese territory or figured I couldn’t get into much trouble on my own. Fortunately, this freedom offered the perfect opportunity to quickly snap a few photos and even record a bit of video in an area where such things are usually forbidden. After walking about 30 metres, I turned around to see if the soldier was still there and when I saw he wasn’t, I immediately reached into my pocket and pulled out my gopro to begin discreetly filming my surroundings. At first there wasn’t much to see apart from trucks, a few buildings, and a border fence covered in razor wire with a Chinese guard tower just behind it, but after walking a bit further I noticed a stone boundary marker about 50 metres in front of the border fence. I walked up to it and discovered that it was a Chinese boundary marker engraved with the national emblem of the People’s Republic of China at the top, along with the Chinese characters for China directly below, followed by the number “83” and “2006” below that, which I assumed indicated that the boundary marker was erected in that year. As a major “border junky”, perhaps even “border nerd”, with a particular fetish for Chinese border crossings, this was a real treat!

Chinese boundary marker.

Chinese boundary marker.

Obligatory selfie with the Chinese boundary marker. I usually don’t take selfies but this was a special occasion!

During my brief stroll towards Chinese territory I walked past about a dozen container transport trucks that were parked in a line leading right up to the border fence. Several Chinese and Tajik truck drivers were milling about next to their vehicles, so I walked up to one of the Chinese drivers and asked if he knew where I was supposed to go once I was on Chinese territory. He pointed to a building with a sign in Chinese that said “Border Defense” about a hundred metres away. A gate attached to the border fence was open, so I simply walked into Chinese territory and headed straight for the border defense building. About 50 metres in front of it, an unarmed Chinese border guard suddenly approached me and asked where I was going, so I handed him my passport and told him that I wanted to enter China. He quickly glanced at my passport and said that I couldn’t enter the building yet because it was lunch time. I asked how long before it would reopen and he replied, “a little while”. Then he pointed towards Tajik territory and told me to walk back to the line of trucks and wait there until he signaled for me to re-enter Chinese territory.

A few metres in front of the actual border fence, with Chinese buildings in front. Note the razor wire.

A few metres in front of the actual border fence, with Chinese buildings in front. Note the razor wire.

When I approached the first truck in line, I noticed a Tajik boundary marker directly across the road from the Chinese boundary marker (I hadn’t noticed it previously because it had been obscured by the line of trucks). It was painted in the colours of the Tajik national flag (red, white and green) but lacked inscriptions. I quickly snapped a few photos and walked back to the trucks to shelter myself from the piercing wind.

Tajik boundary marker just in front of the border fence.

Tajik boundary marker just in front of the border fence.

Another selfie, just to prove I was there!

Location of the Kulma Pass on the map.

Location of the Kulma Pass on the map.

Satellite imagery of the Kulma Pass and surrounding area. Note the large white mass on the right; that’s the Muztagh Ata massif.

Satellite imagery of the Kulma Pass and surrounding area. Note the large white mass on the right; that’s the Muztagh Ata massif.

I stood around in the freezing cold with half a dozen Tajik and Chinese drivers for about 20 minutes before the Chinese border guard gave the signal to cross into Chinese territory. The drivers all immediately jumped into their trucks, while I walked back across the border onto Chinese territory. About 20 metres onto Chinese soil, three or four armed Chinese soldiers approached me cautiously, looking both curious and confused. Hoping to dispel any notion that I was a potential threat, I greeted them cheerily in Chinese and handed one of them my passport. They immediately huddled to gawk at it, while the soldier holding it curiously flipped through the pages. Evidently unable to read English, he handed it back after about a minute and asked where I was from. I explained that I was Canadian but lived and worked in China and had a Chinese wife and daughter. Both he and his colleagues appeared obviously surprised to hear this, but smiled with approval, and even chuckled a bit, before beginning to ask questions about my life in China. While we were chatting, an armored personnel carrier drove up and stopped right in front of us. One of the soldiers next to me immediately announced to the soldiers inside the APC that I was Canadian but lived and worked in China and had a Chinese wife and daughter! The soldiers inside the APC seemed equally surprised to hear this too but were also quite friendly. I handed one of them my passport, then chatted with them for a few minutes until a soldier inside the APC told one of the soldiers standing with me to escort me to a large warehouse-shaped building about 100 metres away.

Once inside the building, we walked into an office where several other soldiers were sitting and drinking tea. The soldier who brought me there briefly explained to them what I was, then handed one of them my passport. After inspecting it for a few minutes, the soldier holding my passport started asking me a long list of questions about my travels. He was polite, even friendly, but wanted to know all the details of my trip: when I had last left China and from where; how I had arrived at the Kulma Pass; why I had been in Tajikistan and where I had travelled in the country. He specifically asked if I had been to any areas of Tajikistan that border Afghanistan or if I had actually been to Afghanistan. I told him I hadn’t, which was partially untrue: I hadn’t been to, or near, Afghanistan during this particular trip, but I had visited Tajikistan a few years prior and, indeed, even travelled to Afghanistan during that trip. Fortunately, that trip was made on an earlier passport, so he had no way of knowing. After the questioning, he asked to see my camera and started looking through all my photos. I literally had a few thousand photos on my memory card and didn’t want him to go through all of them, but I knew there was no way to stop him.

He looked through my camera for a moment, then suddenly stopped and told me to pick up my bag and follow another soldier into an adjoining room, where I was asked to empty the entire contents of my bag onto a stainless steel table. I was also asked to empty all the pockets of my pants and jacket. This soldier was also friendly but very thorough. He took his time closely inspecting every single item I put on the table and asked what several items were, including my compass, handheld gps unit, powerbank, gopro, Sony handycam, and battery chargers for several devices. He also asked if I had any drugs or weapons. When I said no, he looked me straight in the eye, smiled and replied with a phrase that I hadn’t heard before in Chinese (or English for that matter), which translates roughly as, “Drugs are the enemy of mankind”. It was obviously just a bit of propaganda he learned by rote in school or the military, but there was something about the way he said it that really hit me; a certain conviction in his voice that made the phrase seem quite profound at the time.

After inspecting all my possessions, the soldier asked me to turn around and put my hands against the wall before frisking me from head to toe by hand and running one of those wands used for detecting drugs and explosives up and down my body, for good measure. He also ran the wand over all my possessions. When he was finished, I asked him what the wand was for, but he just grinned without speaking and placed a small piece of paper that was on the tip of it, into a machine that is supposed to detect residue from drugs or explosives. Fortunately, the results were negative (as I was expecting them to be, of course). Once all that was over, he told me to pack up and escorted me back to the other room.

The soldier who had interrogated me there and asked to see my camera was still looking at my photos when I reappeared, which was rather surprising since I had been gone nearly an hour. After a moment, he looked up at me, smiled and said he liked my photos! This would have felt more like a compliment if I hadn’t minded so much that he was snooping through the entire contents of my SD card! Oblivious to how I felt, he kindly told me to sit on a bench on the other side of the room and continued to look through my camera. I sat there in silence and stared at him while he continued to look through my photos, which was quite irritating, not least because I had to hold my tongue. About 30 minutes later, a man in civilian clothes walked into the room and was greeted by the soldier holding my camera. The soldier then explained to him that I needed a drive to the customs and immigration building and told me to get up and follow him out of the room. I thanked the soldier but when I got up to leave, I actually had to ask him to return my camera!

The man in civilian clothes drove me from the Chinese border defense post at the Kulma Pass down a winding road to the customs and immigration building about 14 km away. This building is called the “Kalasu Port of Entry” and is located right next to the Karakorum Highway.

A full view of the massive base of Muztagh Ata during the 14 km drive from the Kulma Pass down to the Kalasu Port of Entry.

A full view of the massive base of Muztagh Ata during the 14 km drive from the Kulma Pass down to the Kalasu Port of Entry.

When we pulled up to the building I immediately noticed a customs officer standing outside, staring at me intently. It was clear he was awaiting my arrival. I got out of the car, thanked the driver and greeted the customs officer. After asking for my passport, he told me to please follow him inside. The main hall of the building, where travelers are usually processed, was dark and completely empty. We walked across the hall and he brought me into a side room where two customs officers were sitting. They greeted me politely, asked me to sit down and offered me a cup of boiling water, while the first customs officer handed one of them my passport. After inspecting it for a few minutes, they launched into the same line of questioning as the border defense soldiers back at the Kulma Pass. However, the two customs officers were far more thorough in their line of questioning than any of the border defense soldiers. Ironically, despite being armed and dressed in fatigues, the soldiers were far less intimidating than the unarmed customs officers. To be sure, the former asked plenty of questions, but were warm and friendly; they seemed more curious about me than anything else, whereas the customs agents seemed stern and suspicious. They wanted to know when and how I had left China, everywhere I had been during my trip, who I had been with, and exactly how I travelled from place to place. They even asked for the name of the border crossing where I had entered into Tajikistan from Kyrgyzstan the previous day. When I told them the name, Kyzl Art, they looked confused and asked for the Chinese name, which I thought was an odd question since it wasn’t even a Chinese border crossing. When I told them I didn’t know the Chinese name they immediately looked concerned, even a bit annoyed, so I tried to satisfy them by offering to show them where it was on a map. I actually had several English and Chinese language maps of Central Asia with me, so was able to show them the location of the border crossing in question. Unfortunately, not even the Chinese maps had a Chinese name for it, despite it being located only about 20 km from the Sino-Tajik border.

They also asked detailed questions about my personal life: how long I’d lived in China, how I met my wife, what work she did, where we lived, how old my daughter was, where she was born, etc; they even asked why they weren’t with me! They also inspected my work permit and asked a lot of questions about my job, including my salary, which I was loathe to discuss, so I just made up a number. The impression I got from them was that they suspected I wasn’t who I said I was, which was understandable considering they probably hadn’t encountered many Canadians, or any other third country nationals, trying to enter China through the Kulma Pass; who knows, maybe they even thought I might be a Central Asian terrorist using a fake Canadian passport to sneak into China and carry out an attack, I don’t know.

After a solid hour of questioning, one of the customs officers put my passport into a scanner and began scanning it page by page. I was quite surprised by this since I had never seen this done before in all my numerous experiences crossing many of China’s land borders (not to mention the countless times I’d entered China by air). In all my previous experiences, Chinese customs officers usually only cared if I had a valid visa to enter the country, not about the other countries I’d traveled to. In fact, Chinese customs officers are usually quite easygoing, sometimes to the point of nonchalance; I’ve had many occasions where they quickly inspect my passport, glance up at me to make sure I look like my passport photo, then stamp me into the country, without uttering a single word. On one occasion, while crossing from Kyrgyzstan into China by land, I was detained and interrogated for several hours by Chinese customs agents who suspected that my passport was fake because of water damage, but even then, they only wanted me to provide supporting proof of my identity; they didn’t ask anything about the numerous visas and stamps in my passport from other countries, which actually included Afghanistan (I was using an older passport at that time), let alone scan every single page of my passport! On another occasion, when I entered China by land from Pakistan over the Khunjerab Pass, customs officers had me strip to my underwear and stand in a tiny, upright rectangular box (literally the size of a coffin), to scan my body for drugs, but, again, they didn’t ask me anything about the many stamps and visas from various countries in my passport. In this case, not only did the customs officer scan each page of my passport, she asked for the Chinese names of the countries of every visa, as well as every single entry and exit stamp.

Once she finished painstakingly inspecting every visa and stamp in my passport, a young male customs officer walked into the room and escorted me out to a waiting area in the main hall, where he asked me politely to sit on a bench and wait while he stood guard over me. Several minutes later an older male customs officer walked up to us and asked me in a serious tone if I had any cameras. When I told him I had three, he asked me to remove the memory cards from each and hand them to him, which I did with a labored smile deliberately designed to mask my impatience. I waited on the bench for 2 hours, during which time I had to endure painfully boring conversation with the young customs officer standing guard over me, before the older customs officer returned with my memory cards. Since he had been gone so long, I naturally assumed that he had looked through all or most of the photos and video, and likely even copied them to a hard drive. The thought of him and his colleagues suspiciously inspecting my photos for something incriminating made me feel a bit violated, but my biggest concern was that he might have intentionally deleted some content, particularly my photos and video from the Kulma Pass (fortunately, I later discovered that this wasn’t the case). I was also expecting him to start questioning me about the photos and videos as well, but, fortunately, this didn’t happen either.

More than 3 hours after entering the customs and immigration building, I was finally allowed to walk up to the counter where travelers submit their passports for inspection. In the time that I had been waiting, I saw only one group of about half a dozen Tajik truck drivers enter the building and go through customs inspection, which happened very quickly. When I walked up to the counter I was the only traveler in the building. Fortunately, the customs officer behind the counter was the lady who had scanned every page of my passport, so she processed me quickly as well. While she was processing my entry, I asked her if she knew how many third country nationals had ever entered China through the Kulma Pass and she said less than 10! I asked her when the last one had entered and she said August 2016, which corroborates the claim by the American who posted on Carivanistan that he had crossed at that time.

Once my passport was stamped and handed back to me, I walked out of the building and onto the Karakorum Highway. Despite such a lengthy and tedious ordeal, or perhaps because of it, I was ecstatic. As a self-professed “border junkie”, I had dreamed of crossing the Kulma Pass for years due to its altitude and remoteness (and the bragging rights that come with crossing a border that has been rarely crossed by TCNs). I have no doubt that my ability to speak Chinese was crucial to my success; having a Chinese work permit, and a Chinese wife and child certainly didn’t hurt either! Considering the amount of scrutiny I was subjected to and the length of time it took me to be vetted on the Chinese side, I doubt anyone unable to speak Chinese will be able to make it through anytime soon. It’s still obviously a highly sensitive border crossing and the soldiers and customs officers on both sides, Tajik and Chinese, aren’t keen on letting TCNs through.

Another issue is transportation. There is no bus service across the Kulma, and even though the Kalasu Port of Entry is right on the Karakorum Highway, hitching is the only way to get from there to the nearest town, Tashkurgan, which is 70 km away in the direction of the Khunjerab Pass and Pakistan, while the nearest major city, Kashgar, is 220 km away in the opposite direction. I managed to hitch a ride after thumbing for only about 30 minutes but it was certainly possible that I could have been stuck there indefinitely. The closest village is more than 20 km away but there are no hotels or hostels and there is only one, usually full, bus passing by per day along the KKH in either direction.

View of Muztagh Ata from the Karakorum Highway, right in front of the Kalasu Port of Entry.

View of Muztagh Ata from the Karakorum Highway, right in front of the Kalasu Port of Entry.

A young yak eating paper from a pile of trash next to the KKH.

A young yak eating paper from a pile of trash next to the KKH.

Karakorum Highway (also known in China as the “Sino-Pakistan Friendship Highway” or simply, the G314).

Karakorum Highway (also known in China as the “Sino-Pakistan Friendship Highway” or simply, the G314).

After standing on the side of the KKH with my thumb out for about 30 minutes, a car finally stopped. The driver, a middle-aged Uyghur gentleman, was with his 5 year old son. He promptly told his son to vacate the front passenger seat for me, and we were off in the direction of Tashkurgan, a town 70 km south on the KKH, only about 20km from the Tajik border. Just outside of Tashkurgan, we had to stop at a police checkpoint on the KKH. A Uyghur police officer approached the driver’s window and started speaking to the driver in Uyghur. After less than a minute, the driver got out of the car and handed the police officer his driver’s licence, vehicle registration and travel permit (private vehicles in that part of Xinjiang need a special travel permit because the area is considered a “restricted border zone”). Soon afterwards I realized that the driver appeared to be arguing with the officer but I had no idea what they were saying because they were speaking in Uyghur. A few minutes later, the driver got back in the car and chucked his travel permit and registration down on the console. Then he looked at me with a frown and pointed at the console to indicate that his driver’s license was missing. I immediately understood that the police officer had confiscated his driver’s license but I wasn’t exactly sure why. I asked him in Chinese but he replied with a mix of broken Chinese and Uyghur, which I couldn’t understand. Realizing this, he started the car and drove off in a bit of a huff. 15 minutes of awkward silence ensued before we arrived in the centre of Tashkurgan and he stopped to let me out. I felt guilty, as I assumed that his driver’s license had been confiscated because he offered a ride to a foreign hitchhiker, so I handed him 100 RMB. He accepted it but then reached into his wallet and took out 50 RMB and handed it to me. I’m guessing he would have had to pay a fine or at least go through some sort of bureaucratic rigmorole to get his driver’s license back, so I didn’t mind that he charged me something for the ride.

This map shows my entire route from Bishkek to Tashkurgan, a total distance of 1285 km, covered over 4 days.

This map shows my entire route from Bishkek to Tashkurgan, a total distance of 1285 km, covered over 4 days.

The journey I undertook to cross the Kulma Pass was more than just about going through a set of logistical and bureaucratic procedures to legally travel from one country to another over an officially designated land border crossing; or to put that in plain language, it was more than just about crossing a border. It was about the journey itself. The journey began in Bishkek and ended in Tashkurgan, taking me through the heart of Central Asia and 3 countries (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and China), 2 international border crossings (the Kyzyl Art and the Kulma passes), and along two of the world’s greatest high-altitude highways, the Pamir Highway and the Karakorum Highway. I took in a lot of fantastic mountainous scenery along the way and got to indulge my fetish for remote international borders and travel through restricted border zones. It wasn’t a particularly grueling trip, by the standards of travel I’m used to in that part of the world, but figuring out logistics was challenging at times, as was sitting for long periods in cramped vehicles on bumpy roads. An international border crossing like the Kulma Pass may not hold the same entrancing qualities for the ordinary traveler as it did for a “border junkie/nerd/fetishist” like myself, but the entire journey would surely delight anybody with an interest in travel through this part of the world.

Travel breakdown:

November 12: Bishkek – Osh: 650 km

November 13: Osh – Sary Mogol: 215 km

November 14: Sary Mogol – Sary Tash – Murghab (via Kyrzyl Art Pass): 260 km

November 15 Murghab – Kulma Pass -Tashkurgan: 160 km

Total = 4 days, 1285 km