“In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.”

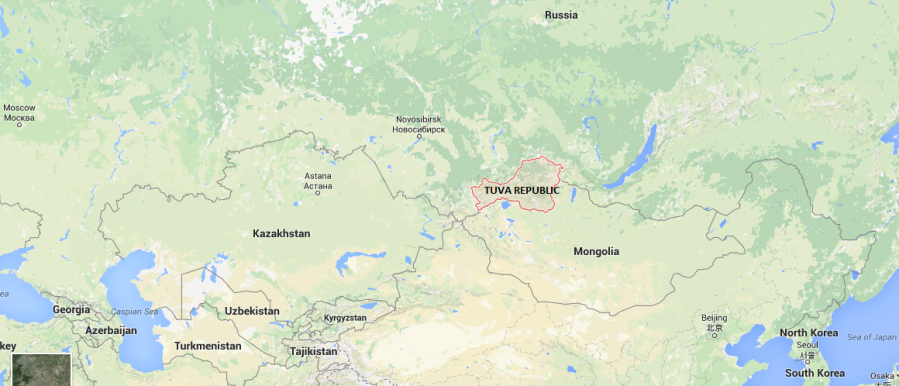

The opening verse of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s famous poem “Kubla Khan”, or “A Vision in a dream: A Fragment”, conjures up a romantic image of a mystical and remote land ruled by the decadent and inscrutable Mongolian monarch, Kubla Khan, the grandson of Chinghis Khan and founder of the Yuan Dynasty, which ruled the Chinese imperium from 1271 to 1368. Although based more on fantasy than a realistic depiction of medieval Mongolia, this poem did much to inform and reinforce the popular 19th century Orientalist concept of the “impenetrable East”, and has continued to grip the Western imagination since it was published nearly two centuries ago. Indeed, I was under its spell when I embarked on my first trip to Mongolia in the spring of 2015.

I had lived in China for nearly a decade and been traveling around Asia for nearly a decade and a half before I finally made my first visit to the Republic of Mongolia, but despite being within such close proximity to it for so long, my understanding of this country was admittedly quite limited. I had already visited the Chinese province of Inner Mongolia (official name: “Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region), which shares a several thousand kilometre long border with the Republic of Mongolia (or “Outer Mongolia”, as it was historically referred to and continues to be referred to in China today), but I had the impression that Inner Mongolia shared little in common with its independent neighbor to the north apart from a long contiguous border. Although Inner Mongolia is a nominal “autonomous region” for China’s ethnic Mongol population, it looks and feels very much like neighboring provinces in northern China, which is unsurprising considering that 80% of Inner Mongolia’s population is Han Chinese, the numerically and politically dominant ethnic group in China (i.e. the one that comes to mind when one refers to someone as “Chinese”).

I had been meaning to visit Outer Mongolia for ages to see for myself just how different it is from Inner Mongolia but never really prioritized it on my list of desired travel destinations. I had actually proposed a trip to Mongolia to a fellow Canadian friend in Beijing soon after I discovered that Canadians didn’t need a tourist visa to visit for up to 30 days, but when he declined to join me, I simply put the idea on the back burner, where it simmered for about a year and a half until an Australian friend in Beijing called me out of the blue one day to say that his Chinese visa was about to expire. He needed to go on a visa run to a neighboring country, so was wondering if I had any suggestions where to go and if I wanted to join him and make a fun trip out of it. This seemed like the perfect opportunity to put my latent Mongolia trip idea into action, so I pitched it to him, and although he initially said that Mongolia wasn’t quite what he had in mind, I managed to convince him that it would be an interesting and worthwhile place to visit. In fact, we had already visited Inner Mongolia together, so I said that this would be a great opportunity to investigate for ourselves just how different Outer and Inner Mongolia were supposed to be from each other. Other selling points that helped convince him are the fact that it’s easy and inexpensive to travel to Mongolia from Beijing, as well as being a relatively inexpensive country to travel in itself. However, most important was the attraction and mystique of visiting a sparsely populated country renowned for its rugged natural beauty, vast empty expanses of desert, steppe, forest and mountainous terrain, and for being the homeland of the world’s last major nomadic society, all right on China’s doorstep! With these points making up the bulk of my pitch, he was sold on the plan within minutes and within a week we were on our way.

Our planning and preparation for the trip was quite rushed, which made it that much more exciting, but also a bit disorganized, as one could imagine. For starters, as an Australian national, my friend would still need to obtain a tourist visa, which I found somewhat surprising since Canadians don’t. At the time, I assumed this was because Canadian mining firms are such big players in Mongolia’s booming mining industry, but later I found out that Mongolia’s largest mining project, which is expected to account for fully one-third of Mongolia’s GDP by 2018, was developed by Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto, so it seems strange that Canadians enjoy visa free status, while Australians, whom I’ve long affectionately referred to as “Canadians down under”, are relegated to the ignoble and inconvenient position of having to apply for a visa. I can only assume this is because Australia, with its increasingly strict immigration policies, makes it harder for Mongolians to visit and/or immigrate than Canada does, so Mongolia is simply reciprocating in the typical tit-for-tat way that governs the world of diplomatic relations.

The plan was for my Australian friend to go to the Mongolian embassy in Beijing and apply for an express visa, which I had read only takes one day, but when he got there he was told that the service had been discontinued! This left us temporarily panic-stricken, since he had to exit China in 4 days, but luckily he also happened to have a Finnish passport by birthright (lucky bastard has never even been to Finland!), and Finns don’t need a visa for Mongolia, so his backup plan was to exit China on his Australian passport, which he needed to do since it contained his Chinese visa, but then produce his Finnish passport at Mongolian customs and try his luck. The reason we both still thought an element of luck would be needed to pull this off was because despite the fact that Finnish passport holders don’t need a tourist visa to enter Mongolia, his Finnish passport was still a virgin (i.e. it had NEVER been used). There wasn’t a single entry or exit stamp from any country to be found on any of its crisp, white pages. We didn’t bother inquiring with the Mongolian embassy or relevant Chinese authorities if this scheme would work, and indeed thought that it would be prudent not to; instead, we both agreed to just go the border and give it a shot, despite the nagging worry that he might be turned back by Mongolian Customs, and maybe even by Chinese customs when attempting to exit China. The reason we worried about the latter possibility is because we thought the Chinese customs agent stamping him out of China might notice that he didn’t have a Mongolian visa in his Australian passport and he didn’t want Chinese customs to know that he was planning to attempt to enter Mongolia on his Finnish passport, as we feared this may raise suspicions somehow. We imagined the Chinese customs agent responding something like this: “Why are you travelling with two passports?” “You want to do WHAT?” “Exit China on one passport and enter Mongolia on another?” “BU XING!” (Chinese for ‘NOT OKAY!’). Although my numerous experiences crossing Chinese borders have been pleasant and smooth (except for one time when I was detained and questioned by Chinese customs when trying to enter China from Kyrgyzstan), I can never help feeling a little nervous each and every time I approach a customs agent from any country, even my own. There’s something about the authority they wield that makes me feel like I’ve committed an unknown offense and will not be permitted to pass unmolested.

The second and equally important problem we had to solve was how to transport ourselves to the Mongolian border on such short notice. We were planning to take the train or bus, or even fly if necessary, but still hadn’t made arrangements with less than 4 days to go. I guess we just kind of took it for granted that there would be lots of trains and buses going to the border, but when we tried to book train tickets we discovered to our dismay that the train was sold out for the day we wanted to travel, which was the day before my friend’s Chinese visa expired; not only that, the train to the Mongolian border only runs once every 3 days, so we didn’t have the option of trying to take it a day earlier. That left the bus or plane, neither of which we were too keen on, but we opted for the bus in the end since it was about a third the price of flying and there were actually 3 buses leaving for the border on the day we wanted to travel. We actually didn’t confirm this until the day before we intended to travel, which wasn’t very smart, and didn’t actually end up purchasing our tickets until 30 minutes before the bus was scheduled to depart, but thankfully we didn’t have any trouble getting them; amazingly there wasn’t even a queue at the bus station, which is rare in Beijing. Feeling relieved and almost smug about our luck getting tickets, we walked to where we thought the bus was supposed to depart but as soon as we handed over our tickets to a man who claimed to be the driver, he told us to follow him and lead us out of the bus station and into a grimy alley instead. Without trying to mask our feelings of suspicion and disapproval, we asked in an obviously annoyed tone if he was taking us to the right bus. He assured us that he was, so we continued to follow him down the alley, which was extremely filthy (even by Beijing standards) until we arrived at a large demolition sight a few minutes later. Two sleeper buses were parked there surrounded by rubble. It was almost 3 pm when we arrived, which is when the bus was scheduled to depart, but as soon as we put our bags under the bus and tried to board, the driver said the bus wouldn’t leave until sometime between 5 and 6 because the buses had to wait for a group of Mongolian traders who wouldn’t be arriving with their cargo until then. I’ve grown accustomed to China’s generally punctual and efficient long distance transport system (air travel being an exception), so I was quite shocked to hear about the delay, especially since the driver had mentioned it so nonchalantly, as if it was to be expected. Slightly annoyed, we next asked him what time the bus would arrive at the border and he told us 6am. This was equally shocking since the sales clerk at the bus station told us it would only take 9 hours but by the driver’s estimation it would take between 12 and 13 hours, depending on when we eventually departed. If that wasn’t bad enough, to add insult to injury, we didn’t finally hit the road until 8pm, 5 hours late!

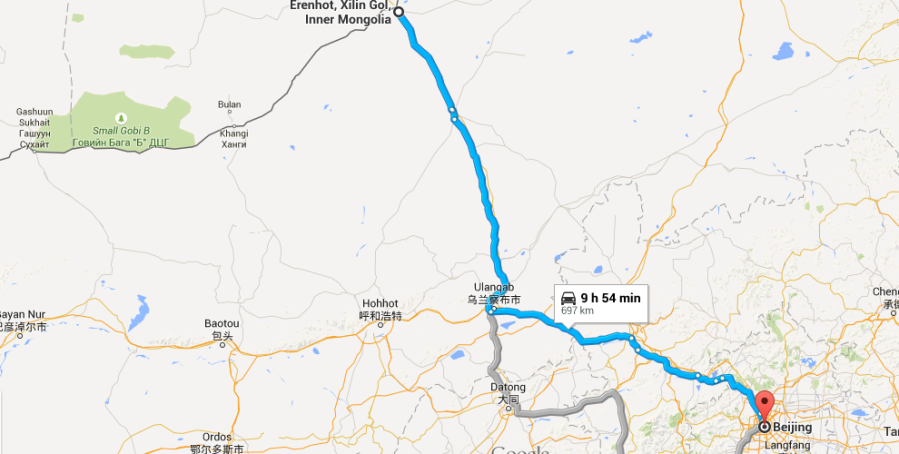

Erenhot

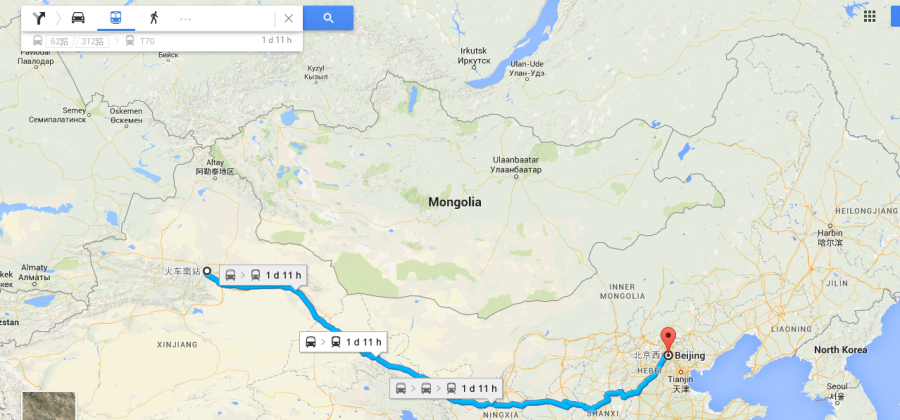

Route from Beijing to Erenhot.

Route from Beijing to Erenhot.

We arrived in the Chinese border town of Erenhot (Ch. “Erlian Haote”) just after sunrise the next morning and immediately took a taxi from the bus station to a large bazaar style market a few kilometers away where Mongolian jeeps congregate to transport travelers across the border. Apparently, pedestrians are not allowed to walk across the border, so we each paid 80 RMB ($13 USD) for seats in a private jeep to ferry us across.

Smack in the middle of the Gobi desert, which is famous for its dinosaur fossils, the Chinese border town of Erenhot has a “Dinosaur Park” across the street from where Mongolian jeeps congregate to transport travelers across the border. At the entrance to the “Dinosaur Park” is a bizarre statue of what looks like two brontosauruses tongue-kissing. Pretty weird.

Smack in the middle of the Gobi desert, which is famous for its dinosaur fossils, the Chinese border town of Erenhot has a “Dinosaur Park” across the street from where Mongolian jeeps congregate to transport travelers across the border. At the entrance to the “Dinosaur Park” is a bizarre statue of what looks like two brontosauruses tongue-kissing. Pretty weird.

Fortunately, we didn’t have to wait around for hours for our jeep to leave, which I read was a possibility. Instead, we left almost as soon as we got in and arrived at the official border crossing in less than 10 minutes.

A large rainbow arch covers the parking lot in front of the Chinese Customs and Immigration building. It’s nice to see China embracing gay pride with such gusto.

A large rainbow arch covers the parking lot in front of the Chinese Customs and Immigration building. It’s nice to see China embracing gay pride with such gusto.

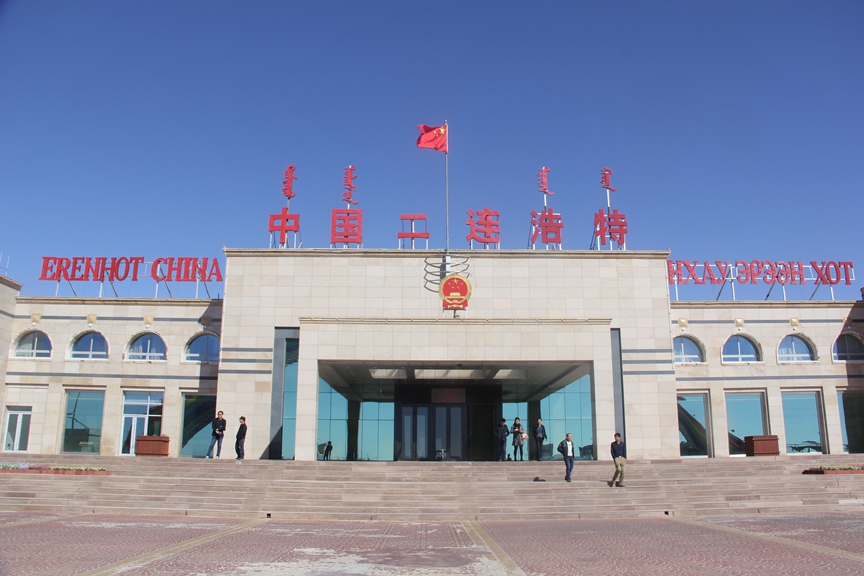

Chinese Customs and Immigration building.

Chinese Customs and Immigration building.

Our driver dropped us in front of the Chinese Customs and Immigration building and said he would pick us up on the other side of it once we had cleared Chinese Customs. Somewhat surprisingly, especially for China, the building was empty; there wasn’t a single person in front of us, so we didn’t have to wait in line, which was a first for me in China! As we approached the Chinese Customs agent though, I noticed that Dion had both his Australian and Finnish passports in hand, so I quickly stopped him and told him to put the Finnish passport away. He was planning to show both passports to the Chinese Customs agent but I told him it probably wouldn’t be a good idea, as it would only complicate matters unnecessarily, so he only presented his Australian passport. The agent noted that his Chinese visa was due to expire at the end of the day but fortunately didn’t notice (or care) that he didn’t have a Mongolian visa, although perhaps he didn’t even know that Australians need a visa to enter Mongolia. Within a mere few minutes of entering the Customs and Immigration building on the Chinese side of the border, we were stamped out of China and standing in no man’s land, where we waited for about 10 minutes until our jeep arrived to ferry us across no man’s land to the Mongolian Customs and Immigration building less than a kilometre away.

Chinese Customs and Immigration building facing the Mongolian side of the border. When I took this photo we had already been stamped out of China and exited this building, which means we were technically standing in no man’s land.

Chinese Customs and Immigration building facing the Mongolian side of the border. When I took this photo we had already been stamped out of China and exited this building, which means we were technically standing in no man’s land.

The process of exiting China had gone very smoothly, so we were in high spirits when we entered the Mongolian Customs and Immigration building but also a bit nervous as this was the “moment of truth” so to speak, the moment we would find out if Dion would be able to enter Mongolia on his virgin Finnish passport. Funnily enough, when we were both standing in front of separate Mongolian Customs agents, his agent asked mine if Finnish nationals needed a visa, which was quite surprising. Throughout my travels, I’ve always taken it for granted that Customs agents know which nationalities require visas to enter their respective countries, but apparently Mongolia is different in that regard (or perhaps that particular agent was still in training, I don’t know). Fortunately, she didn’t seem to notice (or care) that the passport in front of her was as blank as an empty whiteboard, and stamped him in without any questions. The moment she did, both our faces lit up like a Christmas tree. The gamble had paid off!

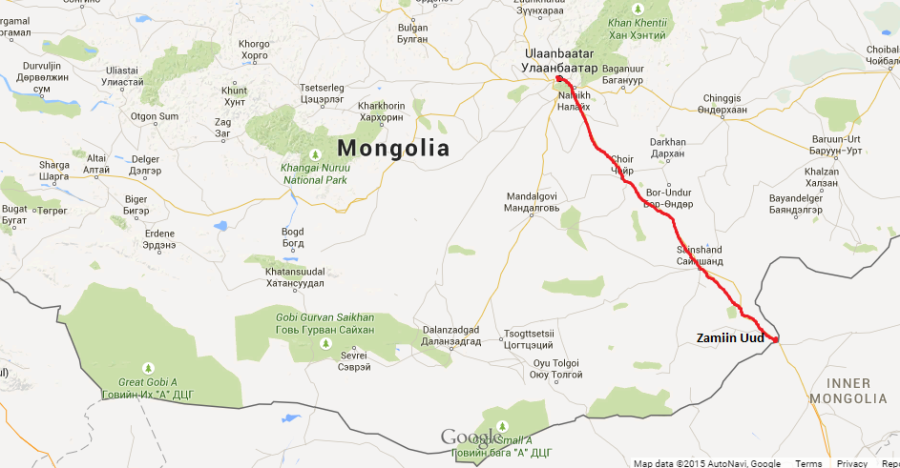

Zamiin Uud

Satellite image showing Erenhot (bottom) and Zamiin Uud (top) with the border running between them.

Satellite image showing Erenhot (bottom) and Zamiin Uud (top) with the border running between them.

A few minutes later we were back in our jeep and on our way to the Mongolian border town of Zamin Uud, which was only a few kilometers from the border crossing. Our driver dropped us off at the train station, where we hoped to buy tickets for a train leaving for Ulaan Baatar that day, but first we needed to find a place to exchange money. After wandering around the entrance to the train station for a few minutes, we found such a place and each bought a few hundred dollars worth of Tugrik, the Mongolian currency. From there we made our way to train ticket sales counter, which was a bit of a challenge to locate. Once we finally found it, we had an even more difficult time finding someone to sell us tickets. The sales counter was devoid of staff so I decided to walk around the building and knock on doors at random hoping to find someone who could help us. This proved futile since I couldn’t find anyone who spoke English but within 30 minutes or so, a sales clerk finally arrived at the ticket counter and sold us two hard sleeper tickets for Ulaan Baater leaving at 7 that evening. By that time it was about 11am, so we decided to find a place to eat nearby.

My first meal in Mongolia. A plate of deep-fried dumplings smothered in mayonnaise with a side of Russian style potato salad and pickled vegetables. Cheap and delicious!

My first meal in Mongolia. A plate of deep-fried dumplings smothered in mayonnaise with a side of Russian style potato salad and pickled vegetables. Cheap and delicious!

After lunch we decided to go to a grocery store next to the train station to buy some beer and snacks, then find some place nice to sit outside and enjoy them.

Myself with a large plastic container of “Gold Mine” brand Mongolian beer.

Myself with a large plastic container of “Gold Mine” brand Mongolian beer.

Dion with a tasty chain of link sausage.

Dion with a tasty chain of link sausage.

With beer, sausages, and a jar of pickles in hand, we walked to a nearby park and sat down on a bench. Since we had about 8 hours to kill before our train was due to depart, we intended to while away the afternoon drinking beer and snacking in the park, as it was a beautiful sunny day. Before we had each finished our first beer though, a group of about half a dozen young Mongolian men suddenly approached us in a somewhat menacing manner and began pointing at our beer and shouting, “NO!”. In an angry tone, one of them told us in broken English that we weren’t allowed to be drinking in the park and then pointed to a group of kids playing soccer on an astroturf field nearby to emphasize his point. Ironically, he appeared to be rather intoxicated himself, although he wasn’t holding an open container of alcohol. We didn’t quite understand why he was so bent out of shape to see us with a couple of open beers in a park, even with kids nearby, but deemed it wise not to try to argue with him and his intimidating assemblage of peers, so we quickly gathered our things and walked back to the train station.

We stopped at the same grocery store outside the train station to get some more beer but instead of both going in, I decided to sit out front and finish my beer, while Dion bought a few more for the two of us. Soon after I sat down, a somewhat haggard middle-aged man suddenly stumbled up to where I was sitting and sat down right next to me. Clearly inebriated, he began staring longingly at my open can of beer. After about half a minute, he pointed at it and gestured with his hand that he wanted to drink from it. Not wanting to upset him, I handed him the can without hesitation and he eagerly guzzled it for a good 10 seconds before handing it back to me. Of course, I wasn’t keen on sharing saliva with a drunken and disheveled stranger (there wasn’t much beer left anyway), so I handed the can back to him and he promptly drained it. I had read that alcoholism was a major social problem in Mongolia but didn’t expect to be confronted with it so soon after entering the country. After experiencing two uncomfortable episodes with drunken strangers in such a short time period, we chose a more secluded spot behind the train station to enjoy a couple of beers in peace.

Inside the station was a pair of beautiful landscape oil paintings depicting an idealized image of Mongolian nomadic pastoralism in classic Soviet socialist realist style.

Inside the station was a pair of beautiful landscape oil paintings depicting an idealized image of Mongolian nomadic pastoralism in classic Soviet socialist realist style.

A single television plays a black and white Soviet film beneath clocks for Moscow, Ulaan Baatar and Beijing, the capital cities of the three countries through which the Trans-Mongolian Railway runs.

A single television plays a black and white Soviet film beneath clocks for Moscow, Ulaan Baatar and Beijing, the capital cities of the three countries through which the Trans-Mongolian Railway runs.

I don’t know much about locomotives but I quite admire them aesthetically, especially older models like this one from the Soviet era. A hammer and sickle emblem on the front suggests Soviet provenance but the double horse logo on the side suggests that this a Mongolian train.

I don’t know much about locomotives but I quite admire them aesthetically, especially older models like this one from the Soviet era. A hammer and sickle emblem on the front suggests Soviet provenance but the double horse logo on the side suggests that this a Mongolian train.

After admiring Mongolia’s rolling stock over several undisturbed beers, we decided to switch up the scenery and wander around downtown Zamiin Uud. With little more than 10,000 inhabitants (by contrast, the population of Erenhot on the Chinese side of the border is 75,000) this sleepy Mongolian border town doesn’t offer much in the way of sights but we did happen to come across a Google truck driving around taking pictures for its Street View service, which is the first time I’ve ever actually seen such a truck in action. What are the chances of it happening in such a tiny place?

After admiring Mongolia’s rolling stock over several undisturbed beers, we decided to switch up the scenery and wander around downtown Zamiin Uud. With little more than 10,000 inhabitants (by contrast, the population of Erenhot on the Chinese side of the border is 75,000) this sleepy Mongolian border town doesn’t offer much in the way of sights but we did happen to come across a Google truck driving around taking pictures for its Street View service, which is the first time I’ve ever actually seen such a truck in action. What are the chances of it happening in such a tiny place?

“Smile Chicken” is an amusing, albeit somewhat odd, name for an “Ice Cream Restaurant”.

“Smile Chicken” is an amusing, albeit somewhat odd, name for an “Ice Cream Restaurant”.

Khaan Karaoke & Pub is such a depressing looking nightlife establishment that I couldn’t help but document it.

Khaan Karaoke & Pub is such a depressing looking nightlife establishment that I couldn’t help but document it.

This kid followed us around for a bit, so Dion bought him a balloon.

This kid followed us around for a bit, so Dion bought him a balloon.

Trans-Mongolian Railway

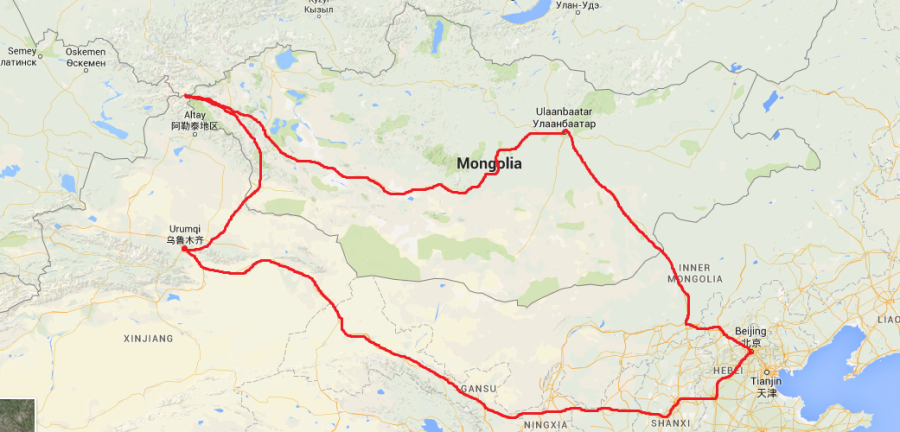

The red line on this map shows the rail route from Zamiin Uud to Ulaan Baatar.

The red line on this map shows the rail route from Zamiin Uud to Ulaan Baatar.

The roughly 800 km journey from Zamin Uud to UB took about 14 hours but was pleasant and comfortable. Mongolia only has one major railway line, the Trans-Mongolian Railway. Totaling just over 1,100 km, it connects the Trans-Siberian Railway with Erenhot (the Chinese border town where we crossed into Mongolia), from where it continues on to Beijing. There are a few spur lines leading to coal mines and an old Soviet military base but passenger rail transport is largely limited to this single line that spans the entire length of the country from north to south. By contrast, the Chinese province or “autonomous region” of Inner Mongolia, which borders Mongolia, has 9 separate railway lines. This discrepancy is no doubt due in large part to the fact that Mongolia , which is actually about 20% bigger in land area than Inner Mongolia, only has an estimated 3 million inhabitants, while the latter has more than 24 million!

About to board our train to Ulaan Baatar. I love train travel and try to ride the train in every country I visit when possible. I particularly enjoy Soviet era trains. They have a sturdy, vintage aesthetic that I find much more appealing than the sterile, plastic aesthetic of modern trains.

About to board our train to Ulaan Baatar. I love train travel and try to ride the train in every country I visit when possible. I particularly enjoy Soviet era trains. They have a sturdy, vintage aesthetic that I find much more appealing than the sterile, plastic aesthetic of modern trains.

We drank several cans of Golden Gobi, a richly flavoured Mongolian beer, on the train and paired them with delicious dill pickles imported from the best pickle producing country on earth, Poland.

We drank several cans of Golden Gobi, a richly flavoured Mongolian beer, on the train and paired them with delicious dill pickles imported from the best pickle producing country on earth, Poland.

Mongolian beer is generally very good, even by Western standards. For reasons that still baffle me, it seems that pretty much all of China’s neighbors brew infinitely better beer than the horse piss that’s mass-produced in China. How can it be that countries with comparatively miniscule populations like Mongolia and Laos produce brew delicious beer, while the world’s most populous country, which also happens to be the world’s largest consumer of beer by volume, produces quite possibly the worst beer in the world?? Chinese made dill pickles are also substandard but that’s much less surprising.

Our hard sleeper car was quite spacious and comfortable. The design was also very different from Chinese hard sleepers. For instance, Chinese trains don’t have single hard sleeper bunks above a seating area. Instead the bunks are stacked in threes, a lower, middle and top bunk, with 2 stacks side by side in one compartment. By contrast, Mongolian hard sleeper cars only have a lower and upper bunk for a total of 4 bunks in one compartment, in addition to the single bunk shown in the below photo, for a total of 5 bunks per compartment, instead of 6 bunks on Chinese trains. Mongolian trains are also quite a bit wider, which makes them much more spacious and comfortable. The clincher though is sit down toilets, an amenity one could never hope to expect in even the most luxurious of Chinese passenger trains.

Dion enjoying a delicious breakfast of canned sardines, kolbasa, dill pickles and rye bread.

Dion enjoying a delicious breakfast of canned sardines, kolbasa, dill pickles and rye bread.

Dion and I posing in front of the train after our arrival in Ulaan Baatar the following morning. For some reason, I neglected to take any scenery photos during the 14 hour journey. Most of it was at night but I did have the opportunity to take a few nice photos in the morning before arriving in UB. I blame the hangover for making me too lazy.

Dion and I posing in front of the train after our arrival in Ulaan Baatar the following morning. For some reason, I neglected to take any scenery photos during the 14 hour journey. Most of it was at night but I did have the opportunity to take a few nice photos in the morning before arriving in UB. I blame the hangover for making me too lazy.

This is the “state emblem of Mongolia”, which is used by the Mongolian government as the official symbol of state. The center depicts a “wind horse”, which is apparently “an allegory for the human soul in the shamanistic tradition of East Asia and Central Asia.”

This is the “state emblem of Mongolia”, which is used by the Mongolian government as the official symbol of state. The center depicts a “wind horse”, which is apparently “an allegory for the human soul in the shamanistic tradition of East Asia and Central Asia.”

Ulaan Baatar

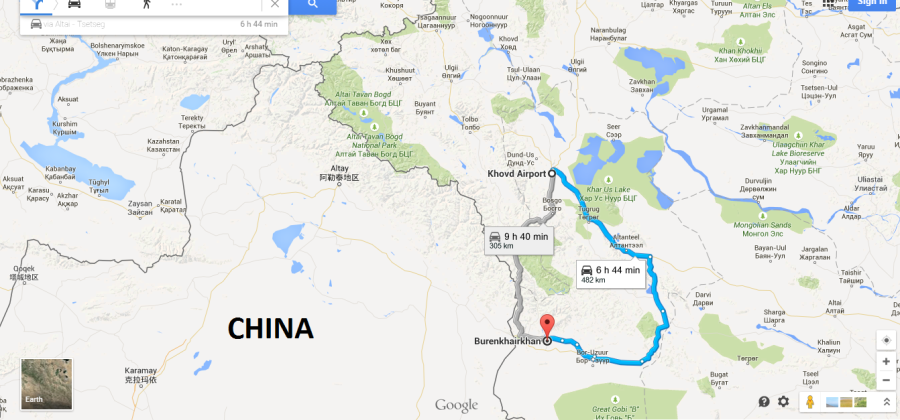

We arrived in UB at about 10:30 in the morning and hadn’t arranged a place to stay beforehand but fortunately our Lonely Planet guide listed a number of youth hostels that were located within a short distance of the train station, so we decided to just walk until we found one that we liked. Within less than 10 minutes we stumbled upon one called Idre’s Guest House while actually on our way to another hostel but decided to check it out anyway because it was also listed in the Lonely Planet. It was clean and cozy and only $8 USD per person per night, so we decided to cut short our search and stay there. We only intended to stay in UB one night as we wanted to leave by bus the next day for distant Bayan Olgii aimag (aimag = province in Mongolian), a remote province in the extreme northwest of the country, bordering both China’s Xinjiang province and Russia. After dropping off our bags and quickly freshening up, we found a place to eat nearby, then took a taxi to the long distance bus station to try to buy bus tickets for the next day. Luckily, we were able to buy tickets for the 1,700 kilometre journey but our relief at having secured them immediately evaporated when the sales clerk said that the journey would take roughly 3 days! We had read as much in the Lonely Planet guide but were hoping that the information was incorrect. The thought of spending 3 days straight on a bus was a painful one but we were committed to the undertaking. We could have taken a 3 hour flight instead like any sane person who could afford it, but decided to grin and bear the bus ride instead in order to A.) save money, and B.) experience traveling across the country by land, which is obviously a more intimate way to experience a country than commercial air travel.

Dion thoroughly enjoyed this delicious dish of tender lamb shank, so tender that the meat slid right off the bone.

Dion thoroughly enjoyed this delicious dish of tender lamb shank, so tender that the meat slid right off the bone.

After buying our tickets we managed to take a city bus back to our hostel (which cost a mere 5% of what it cost to take a taxi from our hostel to the bus station) and from there we walked to a mountaineering store in the centre of the city, called Seven Summits where Dion was hoping to find a pair of crampons. The crampons were for climbing Khuiten Uul, Mongolia’s highest mountain, located in the far northwest of the country, right on the border of China and Russia. At 4,375 metres, Khuiten Uul, which means “Cold Mountain” in Mongolian, isn’t a particularly high or challenging mountain by mountaineering standards but it’s a snow-capped mountain that requires proper equipment to climb it, especially crampons. It was actually Dion’s idea to try to climb Khuiten but he neglected to buy a proper pair of crampons before we left Beijing, so he had to get a pair in UB before we left for Bayan Olgii the following day. The store turned out to be fairly well stocked with high quality imported Western equipment but the prices were prohibitively expensive, so we decided to try a climbing store nearby that turned out to only sell Petzel brand climbing equipment from France. Petzel is a reputable brand but the cheapest crampons at this store cost $152 USD, which was quite a bit more than Dion was planning to spend, especially since I had bought my Chinese made crampons in Beijing for about $25 USD. Unfortunately, his only other option in UB was a $250 USD pair at Seven Summits. Therefore, while he regretted not having bought a pair in Beijing like I had, he had no choice but to bite the bullet and fork over $152 for the French pair. He tried to offer them $150 USD in cash but they refused and actually seemed a little annoyed that he tried to bargain with them, even for a mere two dollars. Later we came to realize that quite unlike the Chinese, Mongolians weren’t into bargaining, with foreigners at least, and sometimes even seemed offended by our attempts to negotiate prices. The crampons were clearly of high quality though, so $152 seemed reasonable enough, and he definitely needed a pair.

After purchasing the crampons, we decided to walk over to Chinghis Square, which was only a few blocks away. The main public square in UB, Chingis Square, is the Mongolian equivalent of Tiananmen Square in Beijing but even more impressive, in my opinion.

The square is dominated by this sleek, palatial colonnade with a massive bronze statue of Chinghis Khan at its center, flanked by statues of his son and successor Ogedei Khan and grandson, Kublai Khan who ruled as Emperor of China during the Yuan Dynasty.

The square is dominated by this sleek, palatial colonnade with a massive bronze statue of Chinghis Khan at its center, flanked by statues of his son and successor Ogedei Khan and grandson, Kublai Khan who ruled as Emperor of China during the Yuan Dynasty.

The two equestrian statues on either side of the Chingis Khan statue seen in this photo are actually not of his son and grandson but instead are of his two most trusted military retainers; the statues of Ogedei and Kublai are outside the photo at the far ends of the building.

The two equestrian statues on either side of the Chingis Khan statue seen in this photo are actually not of his son and grandson but instead are of his two most trusted military retainers; the statues of Ogedei and Kublai are outside the photo at the far ends of the building.

The statue of Kublai Khan is on the right corner but is obscured by columns at this angle.

The statue of Kublai Khan is on the right corner but is obscured by columns at this angle.

At the centre of Chinghis Square is a statue of Damdin Sukhbaatar, a leader of Mongolia’s successful 1921 revolution, in which the Soviet Red Army helped Mongolian nationalists liberate the country from Chinese occupation. Ulaan Baatar actually means “Red Hero” in Mongolian and was chosen as the new name for the city after the establishment of the Mongolian People’s Republic in 1924.

The statues on Chingis Square are a testament to just how much Mongolians both cherish their independence and maintain a strong sense of national historical greatness. They are extremely proud of the global conquests of Chingis Khaan and his successors 800 years ago but also jealously guard their new-found national independence, which was only truly realized after the fall of the Soviet Union. During the Soviet era, Mongolia could claim de jure independence but was in actuality a de facto satellite state of the Soviet Union for most of the 20th century. Before that, the Manchu Qing Dynasty, which ruled China for more than 250 years, also managed to rule both Inner and Outer Mongolia for almost as long. However, when the Qing dynasty fell in 1911, Outer Mongolia quickly seized the opportunity to throw off the Manchu yoke and declare independence. The newly founded Republic of China resolutely opposed this, but was eventually forced by the Soviet Union to relinquish all territorials claims to Outer Mongolia. Today, Mongolia remains uncomfortably sandwiched between its two powerful neighbors and former overlords, China and Russia. Landlocked and bordering only two countries, Mongolia also happens to be the least densely populated country in the world, so given its history, geographic vulnerabilities, and sparse population, it’s unsurprising that Mongolians are so jealous of their independence.

The rest of our day was spent walking back from Chingis Square to our hostel. Apart from the square and a few nearby monuments and government buildings, there isn’t a whole lot of sightseeing to be had in UB, but it’s an interesting enough city to explore in good weather, which we were lucky enough to enjoy. UB is a fairly dilapidated, ramshackle affair but with a certain post-Soviet charm reminiscent of Central Asian capitals like Bishkek and Dushanbe.

It was also interesting to see traditional Mongolian gers like these surrounded by more typically “urban” brick and mortar housing, ie, the Soviet Era tenements in the immediate background.

It was also interesting to see traditional Mongolian gers like these surrounded by more typically “urban” brick and mortar housing, ie, the Soviet Era tenements in the immediate background.

Commonly known as a “yurt” in Western parlance, Mongolian gers are traditional nomadic dwellings still used by about a third of the country’s population. Each Mongolian ger typically weighs about 250 kg and is designed to be completely portable and quickly assembled. Most gers in Mongolia are scattered throughout the country’s vast steppe and Gobi desert regions but tens of thousands also exist in “ger suburbs” on the outskirts of UB. Unlike in the countryside where ger dwellers typically burn animal dung for heating and cooking, urban gers are mainly heated by crude coal-burning stoves, which contribute to the capital’s frightening levels of air pollution, especially during its long and blistering cold winters.

UB is clearly a city experiencing rapid transformation and growth. With a population of roughly 1.3 million, its population accounts for roughly 40% of the national total and that percentage is likely to increase as the country’s mining boom propels economic growth and modernization. Unfortunately, one downside of that growth is the horrendous traffic congestion and air pollution. As a long time resident of Beijing, I’m all too familiar with both, but UB is even worse. Interestingly, however, while most of the cars in Beijing are new Chinese-made models, the clear majority of cars in UB are used Japanese imports, particularly the Toyota Land Cruiser, but also the Toyota Prius, which was very surprising to see. Even in the tiny border town of Zamiin Uud, I was shocked that the Prius was so popular. And the reason I know that most of the Japanese brand cars are second-hand imports from Japan is because the steering wheels are on the right side (Mongolians drive on the right side of the road so these cars weren’t designed for the Mongolian market), while most also have stickers and insignia that indicate that they were previously driven in Japan.

Another observation about UB worth mentioning is the large number of alcoholic beverage containers (mostly vodka bottles) littering the streets, which points to the country’s epidemic of alcoholism. Ironically, we didn’t actually see anyone drinking in the streets though, which is probably due to the fact that there is a nation-wide ban on public alcohol consumption that is apparently strictly enforced with steep fines. This likely explains why Dion and I got so much flack from that group of young men in Zamiin Uud for drinking beer in a public park (for the record, we didn’t read about this ban until arriving in UB). We also read that bars in UB are only permitted to serve drinks until 11:30 pm and must close at midnight, which seems rather prudish, but is probably another attempt to combat alcoholism. Partially for that reason, we didn’t even bother going to a bar during our only night in UB, but instead bought some beer at a convenience store and drank it in our hostel. The main reason though, was that we still had a few errands to run the next day and didn’t want to be hung over for the beginning of our 3 day bus journey which was scheduled to begin the following afternoon.

To see more photos of Ulaan Baatar, please click here.

Bus to Bayan Olgii

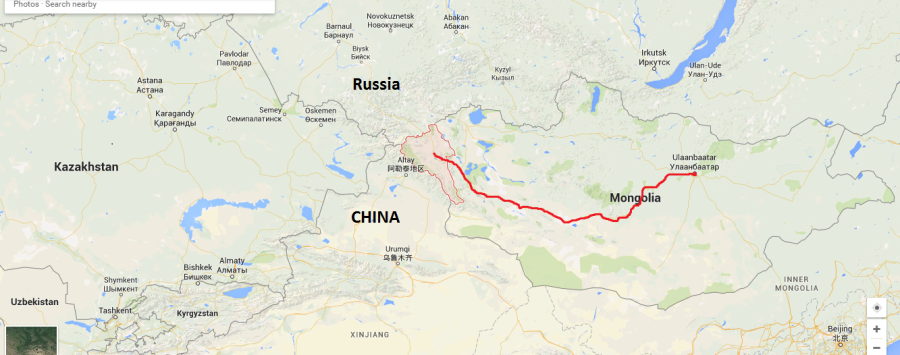

The red line is the roughly 1,700 km route we took from UB (on right) to the town of Olgii, provincial capital of Bayan Olgii province (outlined in red).

The red line is the roughly 1,700 km route we took from UB (on right) to the town of Olgii, provincial capital of Bayan Olgii province (outlined in red).

Our bus to Bayan Olgii aimag (province) was scheduled to leave at 3pm. We arrived at the bus station at 2:30 by taxi but had trouble finding our bus even with the help of our taxi driver. When we did finally find it after about 15 minutes of asking around, we were horrified to discover that it wasn’t a sleeper bus or even a relatively comfortable sitting bus; it was a beat up old, Korean clunker that looked more like a public transit bus than a long distance passenger coach. Living in China for so long, I’d grown accustomed to travelling on modern sleeper buses, which albeit not the most comfortable option for long distance travel, are certainly far more comfortable than sitting upright, especially for 3 days straight! When we got on board we also discovered that nearly half the bus was full of cargo. To make matters worse, we drove to another bus stop a few kilometers away where even more cargo was loaded onto our bus, which meant that we didn’t get out of the city until 5pm. Fortunately, there were only 10 passengers on the bus, including Dion and I, so I actually ended up getting two seats to myself, which was a great relief.

Quite ingeniously, Dion turned several big boxes of cargo into a comfortable bed, which he slept on in his sleeping bag. Neither of the two drivers seemed to mind, so he was able to sleep like this for two nights.

Quite ingeniously, Dion turned several big boxes of cargo into a comfortable bed, which he slept on in his sleeping bag. Neither of the two drivers seemed to mind, so he was able to sleep like this for two nights.

On the second morning our bus broke down and the drivers had to almost completely disassemble the engine. It took them more than 6 hours to get it running again. Luckily, we were able to pass the time at a roadside canteen called a “guanz” where we had lunch and spent hours sipping salty milk tea.

On the second morning our bus broke down and the drivers had to almost completely disassemble the engine. It took them more than 6 hours to get it running again. Luckily, we were able to pass the time at a roadside canteen called a “guanz” where we had lunch and spent hours sipping salty milk tea.

We stopped at a guanz twice a day for meals. The traditional Mongolian food they served was tasty enough but several hours after eating dinner at one on the second night, I was awaken by an evil rumbling in my stomach that quickly progressed to my bowels. I tried to ignore the unpleasant sensation for a few minutes but was eventually forced to ask the driver to stop the bus and let me out. I barely made it 2 metres from the bus before I had to drop my pants and relieve myself in the darkness. About a minute later, I heard someone else get off the bus and walk toward me, which filled me with panic because I was still squatting with my pants around my ankles. It turned out to be one of the male passengers and he was practically right on top of me before he realized I was there. Once he did, I pulled my pants up half way and scurried away in embarrassment until I was about 15 metres from the bus, where I again quickly assumed a squatting position. To my great dismay, however, less than a minute later a female passenger from the bus suddenly walked towards me and squatted about 3 metres in front of me before suddenly realizing that I was there, at which point she jumped up in alarm and scurried deep into the darkness and out of sight. It was an embarrassing fiasco at the time but I was soon able to laugh it off and have since retold it many times to amused listeners.

A typical meal at a roadside guanz. I can’t remember exactly what was in this bowl but I think it was a combination of dry, slightly coarse noodles with pieces of mutton, onion and potato. And of course, every meal is accompanied by bowls of salty milk tea.

A typical meal at a roadside guanz. I can’t remember exactly what was in this bowl but I think it was a combination of dry, slightly coarse noodles with pieces of mutton, onion and potato. And of course, every meal is accompanied by bowls of salty milk tea.

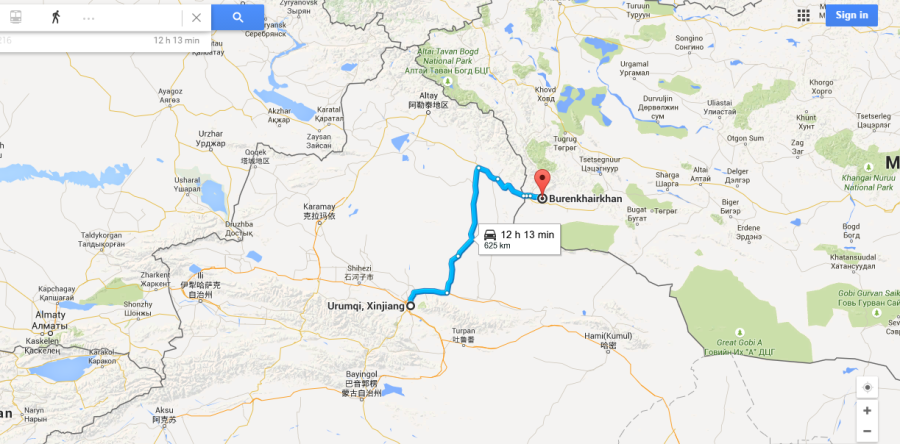

We got along well with the other passengers, some of whom spoke a bit of English. I would even go so far as to say we bonded with a few of them during the journey. We all shared food with one another and got to know each other a little bit as well. All the Mongolian passengers actually turned out to be ethnic Kazakhs, a Muslim minority ethnic group in Mongolia who make up about 4 percent of Mongolia’s population. While citizens of Mongolia, they are not ethnic Mongols, most of whom are nominally Buddhist. One of the Kazakh passengers was a 23 year-old soldier, two others were university students and a few others were petty traders. The traders were on their way back to Bayan Olgii province from the Chinese border town of Erenhot, roughly 2,500 kilometres away, where they had gone to buy trade goods to resell in Bayan Olgii. What was most astonishing about this though was the fact that Bayan Olgii province actually borders China’s Xinjiang province, which has a border crossing with Mongolia, so I couldn’t understand why they had made a 5,000 km round trip journey to buy goods in Erenhot when they could have travelled a mere few hundred kilometers to Xinjiang and bought goods there. I asked them this question but didn’t get a clear answer. From what I could gather, it seemed like they were saying they weren’t allowed to cross the border into Xinjiang but this didn’t really make sense, since I had read that the border crossing was open and traders from both sides use it. Perhaps prices are simply lower in Erenhot than Xinjiang, so they could make bigger profits even when factoring in the higher transport costs of travelling a much further distance. But then again, I’m only speculating.

Triple thumbs up with Dion, the soldier and a university student.

Triple thumbs up with Dion, the soldier and a university student.

We passed very few automobiles during our nearly 1,700 km journey, probably only one every couple of hours, if that. We stopped here somewhere in the middle of the Gobi desert because the bus next to us had broken down and our driver offered to help.

We passed very few automobiles during our nearly 1,700 km journey, probably only one every couple of hours, if that. We stopped here somewhere in the middle of the Gobi desert because the bus next to us had broken down and our driver offered to help.

At least 3 quarters of the journey was literally off-road, driving on dirt tracks through dusty, barren landscapes. The Mongolian government claims the country has 50,000 km of “roads” but only 5,000 km are paved.

At least 3 quarters of the journey was literally off-road, driving on dirt tracks through dusty, barren landscapes. The Mongolian government claims the country has 50,000 km of “roads” but only 5,000 km are paved.

Evidence of human habitation along the route our bus traveled was slim to say the least, consisting mainly of the odd lone ger every few hours or tiny mixed ger/brick and mortar settlements. Three times the size of France but with only 3 million people (France has about 67 million), Mongolia is the least densely populated country in the world and when you leave the capital, which accounts for 40% of that total, the paucity of human settlement over vast tracts of land is clearly evident.

Without knowing that I was Canadian, this gentleman proudly announced to me that Falcon Drilling was a Canadian company.

Without knowing that I was Canadian, this gentleman proudly announced to me that Falcon Drilling was a Canadian company.

The mining sector in Mongolia has been booming for the past decade and Canadian mining firms have a significant presence in the country, but although Mongolia has become a magnet for international mining companies, the vast majority of rural Mongolians still depend of animal husbandry for their livelihoods. Mongolia has 3 million people and over 40 million livestock, mostly sheep and goats but also plenty of horses, cattle and camels.

During our last stop at a guanz before arriving at our destination, Dion was challenged by the young soldier on our bus to an arm wrestling match, which he quickly lost.

Dion put up a valiant, albeit brief, fight but didn’t really stand much of a chance. The soldier asked if I wanted to challenge him next but I resolutely declined. The man standing between them in this photo and smiling took up the challenge though, and quickly defeated him, which neither I nor Dion expected.

Dion put up a valiant, albeit brief, fight but didn’t really stand much of a chance. The soldier asked if I wanted to challenge him next but I resolutely declined. The man standing between them in this photo and smiling took up the challenge though, and quickly defeated him, which neither I nor Dion expected.

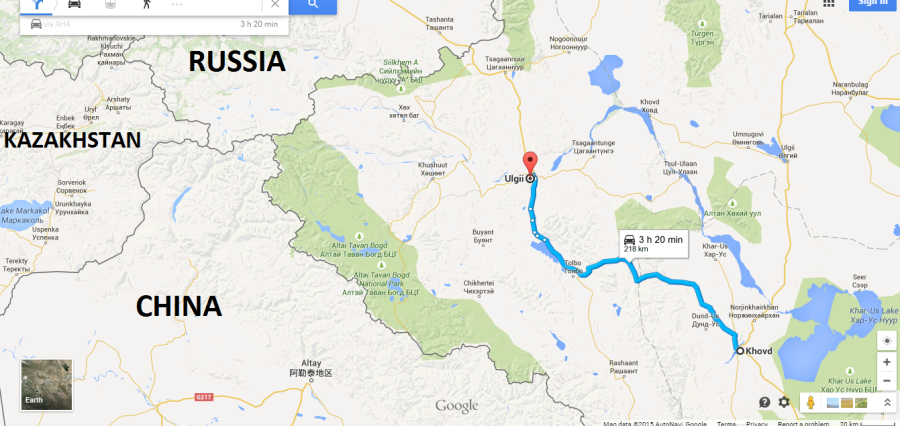

We arrived in the town of Olgii, capital of Bayan Olgii province, about 56 hours after leaving UB, which was much sooner than the 72 hours we had anticipated. The journey, punctuated by two breaks per day for meals and several breakdowns, (one of which lasted 6 hours) wasn’t easy but it also wasn’t that bad. Dion was able to stretch out on a stack of boxes at the back of the bus and sleep comfortably in his sleeping bag, while I was lucky enough to have two seats to myself, which made the trip a whole lot more tolerable than if I had only one. It was a bumpy ride to be sure and quite uncomfortable at times, but we had fun interacting with and getting to know the other passengers. The worst parts of the trip for me were my embarrassing bout of diarrhea and coming down with a nasty little chest cold half way through the journey. I also discovered during the trip that my crampons had fallen out of a side pouch on my knapsack, which put me in a foul mood for about a day and a half. I looked everywhere I could during the journey but to no avail. When we finally arrived at our destination though, I decided to give it one last-ditch effort, which meant hauling a bunch of the boxes off the bus to check if the crampons had somehow been buried under them. Fortunately my hunch paid off and my efforts were rewarded when I found them on the floor of the bus, where they had been buried underneath a large stack of boxes. Finding my crampons lifted my spirits considerably. I had been fretting over them for most of the journey, since without them I wouldn’t be able to climb the mountain, which was the main reason we had travelled 56 hours to this remote corner of Mongolia.

Bayan Olgii

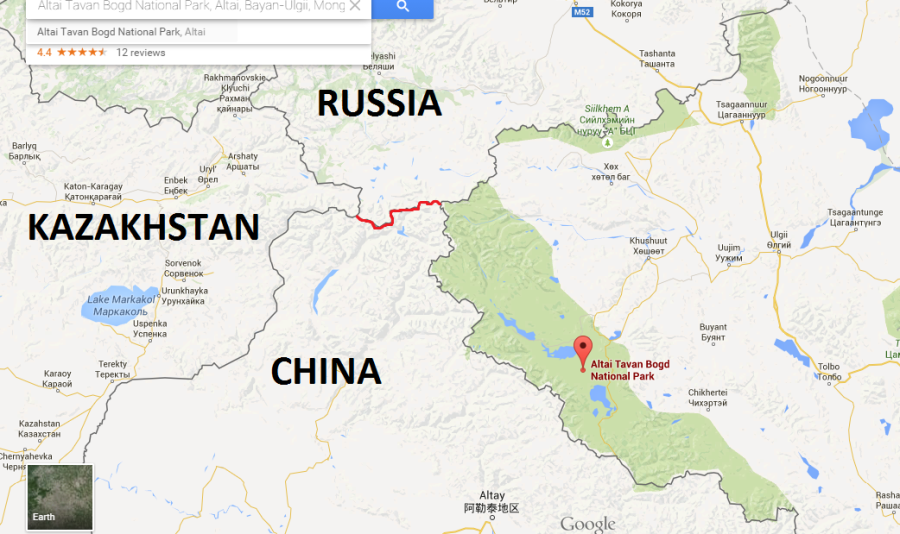

Bayan Olgii is outlined in red at the centre of this map.

Bayan Olgii is outlined in red at the centre of this map.

Located in the far northwestern corner of Mongolia, bordering both Russia and China, Bayan Olgii is the westernmost aimag (province) in Mongolia and probably the most remote of all 21 aimags in the country. Bayan Olgii is also unique for being the only Muslim and Kazakh-majority province in Mongolia. Almost 90% of the approximately 90,000 people living in the province are ethnic Kazakhs, a Turkic Muslim ethnic group from Central Asia and the ethnic majority in Kazakhstan, which also happens to be the largest Central Asian “Stan” country. By contrast, Mongolia’s main ethnic Mongol subgroup, the Khalka Mongols, who account for roughly 80% of the country’s population, account for only about 1% of the poputlation of Bayan Olgii. The Kazakh language is also widely spoken as a mother tongue in the province and while Mongolia doesn’t share a border with Kazakhstan, Bayan Olgii is only separated from the latter by a 38 kilometer strip of border between Russia and China’s Xinjiang province. Bayan Olgii’s close geographic and cultural proximity to both Kazakhstan and China’s Turkic Muslim majority Xinjiang province give it a distinctly Central Asian flavor not found in the rest of Mongolia. The provincial capital, Olgii, which has about 30,000 residents, is a dusty, windswept frontier town surrounded by mountains with several mosques, a madrassa (Islamic school) and a large bazaar. Olgii is also only about a 3 hour drive from the Russia border.

A minaret from one of several mosques in Olgii.

A minaret from one of several mosques in Olgii.

We arrived in Olgii at about 8 pm and made our way by foot to a hostel run by Blue Wolf Travel, one of several travel companies in town that cater to foreign tourists. Bayan Olgii is far off Mongolia’s backpacking circuit but increasing numbers of intrepid travelers have been going there over the past decade to explore its pristine national parks and experience traditional Kazakh cultural activities like eagle hunting, which, somewhat ironically, has apparently been better preserved there than in Kazakhstan. For instance, Bayan Olgii province is reported to have about 360 trained eagle hunters (people who use eagles to hunt small game like hares and foxes, not people who hunt eagles!), more than in all of Kazakhstan, and several eagle hunting festivals are held each year throughout the province to showcase this tradition for tourists.

The sky over Olgii was full of golden eagles. I’ve never seen so many eagles at one time before; they’re to Olgii what pigeons are to New York City.

The sky over Olgii was full of golden eagles. I’ve never seen so many eagles at one time before; they’re to Olgii what pigeons are to New York City.

This is probably a young male (males are smaller than females), but we also saw many large eagles.

This is probably a young male (males are smaller than females), but we also saw many large eagles.

The “hostel” at Blue Wolf Travel consists of an outdoor wooden deck with about a dozen miniature gers on it; this was ours.

The “hostel” at Blue Wolf Travel consists of an outdoor wooden deck with about a dozen miniature gers on it; this was ours.

The gers have electrical outlets but the flow of electricity to the town, which comes from neighboring Russia, is highly unreliable. The gers also lack heating so it got pretty cold at night. There is a separate building with washrooms and showers for both genders but we were unable to get hot water during the two nights we stayed there, so didn’t bother showering. The $10 USD per person accommodation fee included a hearty breakfast though, so we were pretty satisfied.

The gers have electrical outlets but the flow of electricity to the town, which comes from neighboring Russia, is highly unreliable. The gers also lack heating so it got pretty cold at night. There is a separate building with washrooms and showers for both genders but we were unable to get hot water during the two nights we stayed there, so didn’t bother showering. The $10 USD per person accommodation fee included a hearty breakfast though, so we were pretty satisfied.

The main reason we decided to stay at Blue Wolf Travel wasn’t for the accommodation though, but instead because the owner of our hostel in Ulaan Baatar told us that the former could help us obtain both the necessary permit and pay a separate fee to enter the national park where the mountain we wanted to climb, Khuiten Uul, is located. We each needed to pay a 3000 tugrik ($1.50 USD) “Protected Area Entry Fee” to the Minister of Environment and Green Development but, more importantly, we also had to obtain a border permit from the Mongolian military because the national park borders both Russia and China. The border permit is technically free but the relevant authority is apparently unwilling to issue them directly to foreigners, so we had to use a Mongolian citizen to apply on our behalf, which Blue Wolf Travel was willing to do for a modest $10 USD fee per person. We had actually called Blue Wolf Travel from UB and asked them to apply for the permits for us before we arrived in Olgii so that they would be ready when we arrived, which they agreed to do, but when we finally arrived 3 days later, we discovered that they hadn’t even submitted our applications, which was quite disappointing. The owner of Blue Wolf Travel had even asked us to email photos of our passports, which we did, and said we could each pay him the $10 service fee after we arrived in Olgii and picked up the permits that he said would be waiting for us. However, when we actually met the owner at his office in Olgii, he explained that in order to apply for the permit he not only needed to provide copies of our passports, but also the ID and vehicle registration of the driver that planned to drive us from Olgii to the entrance of the national park. Strangely, he hadn’t mentioned any of this when I had first spoken to him on the phone from UB. Dion and I knew that Olgii was about 180 kilometres from the spot where we intended to enter the national park, and that there was no public transport, but we had no idea that we needed to already have a driver arranged to simply apply for the border permit.

As it turned out, one of the traders on our bus from UB to Olgii lived in a village about halfway between Olgii and the national park. During the bus journey he had offered to drive us from his village to the park for a fee, which we agreed to, so when we found out that we needed a driver to apply for the border permit, we told the owner of Blue Wolf Travel to call the man who agreed to be our driver, whose name was actually “Bold”, and he came to the office to meet us a short while later. Unfortunately, not long after arriving at the office and greeting us happily, our would-be driver, Bold, suddenly left in a bit of a huff. He and the owner of Blue Wolf Travel had been speaking in Kazakh for about 10 minutes and the conversation eventually became quite animated, at which point Bold suddenly stood up and left without saying goodbye. Feeling a bit confused, we asked the owner of Blue Wolf Travel what had just happened and he explained that Bold wasn’t willing to provide his ID and vehicle registration for our permit application because the owner had told him that he would also have to be “responsible” for us while we were in the park. This added layer of complexity to the application process came as quite a surprise to Dion and I, so we asked what “responsible” actually meant in this context. The owner replied that several years ago a couple of Frenchmen had actually walked the 180 kilometres from Olgii to the national park and once inside, one of them had crossed the border into Russia and was detained by Russia border guards, so ever since then, the Mongolian army has required foreigners to be driven to the park and their drivers have to be registered as part of the permit application. The owner told us not to worry though because, low and behold, he had a driver who could provide his ID and vehicle registration for the permit application who was also willing to take on the nebulous burden of “responsibility”. Naturally, I was beginning to feel a bit suspicious and frustrated at this point, so I asked how much his driver cost, and was perturbed by his answer: $180 USD. He broke the cost down as follows: $60 USD for the driver to drive us to the park and $40 to drive himself back without us, plus another $80 for gas! I had read in the Lonely Planet that travel agencies in Olgii could arrange a 5 seater jeep for about $150 USD, so I was expecting the price to be high, but I was definitely annoyed when the owner quoted us even higher. The trader we had met on the bus, Bold, offered to drive us for less than half that, so the prospect of paying $180 USD for a 180 kilometre journey was that much more irksome. Unfortunately, we didn’t have much of a choice. Obviously aware of our displeasure, the owner of Blue Wolf Travel told us that we didn’t have to use his driver and could try to find one on our own who was willing to provide his ID and vehicle registration but I think Dion and I correctly perceived this offer as rather disingenuous. Of course, he had a financial incentive to ensure that we used his driver, so we suspected that he had intentionally scared Bold into not being our driver by telling him that he had to accept “responsibility” for us while we were in the park. I mean, what could that possibly mean anyway? Regardless of who drove us to the park, once we were inside, there was nothing any driver could do to prevent us from illegally wandering across the border into Russia or China, so his explanation simply didn’t add up. Call me paranoid, but Dion and I could both clearly see the forest for the trees at that point. As frustrated as we were of feeling like we were about to be ripped off though, we decided to use his driver because we didn’t want to waste anymore time. We had expected that our permits would be ready as soon as we arrived in Olgii but here it was the morning after our arrival, and Blue Wolf Travel still hadn’t even applied for them, which meant that we would have to stay in Olgii at least one more night before leaving for the park. After hemming and hawing for a little while, we begrudgingly forked over the $180 USD.

Once we had our travel arrangements sorted out, Dion and I walked to the bazaar to buy food supplies for our climb since there wouldn’t be anywhere to buy provisions once inside the national park.

Downtown Olgii. Note that there are not one but two silver Toyota Prii (plural of Prius) in the lower right hand corner of this photo. It’s truly astonishing how popular the Toyota Prius is in Mongolia!

Downtown Olgii. Note that there are not one but two silver Toyota Prii (plural of Prius) in the lower right hand corner of this photo. It’s truly astonishing how popular the Toyota Prius is in Mongolia!

On the way to the bazaar we passed what is surely the world’s most depressing, dilapidated (and dangerous!) Soviet-era children’s slide.

On the way to the bazaar we passed what is surely the world’s most depressing, dilapidated (and dangerous!) Soviet-era children’s slide.

We also passed the offices of the Bayan Olgii Aimag Democratic Party. Mongolia is a multiparty parliamentary republic and has made impressive progress toward instituting a functioning democratic government since the peaceful 1990 Democratic Revolution, which lead to the bloodless overthrow of authoritarian one-party socialist rule during the period of the Mongolian People’s Republic from 1924 to 1992.

Bayan Olgii Aimag Democratic Party headquarters.

Bayan Olgii Aimag Democratic Party headquarters.

The local museum. We didn’t bother going in.

The local museum. We didn’t bother going in.

I really love old socialist realist style Soviet era statues. There’s something so austere and formidable about them.

I really love old socialist realist style Soviet era statues. There’s something so austere and formidable about them.

Many Soviet-era statues are overtly and intentionally militant. This one depicts what appears to be a Mongolian war hero of some kind brandishing a revolver.

Many Soviet-era statues are overtly and intentionally militant. This one depicts what appears to be a Mongolian war hero of some kind brandishing a revolver.

The instruments on display in this photo are called dombra, a two string lute common to the Central Asian “Stan” countries and Turkic regions of Russia. It’s quite similar to the dutar, which is popular among the Turkic Muslim majority of China’s Xinjiang province as well as in Afghanistan and Iran.

The instruments on display in this photo are called dombra, a two string lute common to the Central Asian “Stan” countries and Turkic regions of Russia. It’s quite similar to the dutar, which is popular among the Turkic Muslim majority of China’s Xinjiang province as well as in Afghanistan and Iran.

One of the food items we stocked up on were these white chunks of rock-hard goat’s milk curd. You can easily break your teeth on this stuff and it has a very pungent tanginess that takes some getting used to, but it’s an ideal food for energy intensive wilderness activities like trekking and mountain climbing because it’s both compact and high in nutrients.

One of the food items we stocked up on were these white chunks of rock-hard goat’s milk curd. You can easily break your teeth on this stuff and it has a very pungent tanginess that takes some getting used to, but it’s an ideal food for energy intensive wilderness activities like trekking and mountain climbing because it’s both compact and high in nutrients.

We also stocked up on plenty of meat for added nutrition. I think this is horse but we bought mutton because it was a lot cheaper.

We also stocked up on plenty of meat for added nutrition. I think this is horse but we bought mutton because it was a lot cheaper.

With plenty of provisions, including butane gas for cooking and boiling water, we left Olgii the next morning just after 6. Our driver picked us up in an old Russian UAZ jeep, which I’d travelled in several times before throughout my travels in other parts of Central Asia. The UAZ is a symbol of Soviet era pride that many Russians are still proud of, and rightly so. They are dependable, robust and long lasting vehicles, which is evidenced by their ubiquity across the most rugged and remote parts of Central Asia. Of course, another important reason for their popularity is that they cost a fraction of a Toyota Land Cruiser, but so do Chinese-made jeeps and you hardly see anyone driving them. I dare say a 30 year old UAZ would outperform a brand new Chinese-made contraption any day. But I digress.

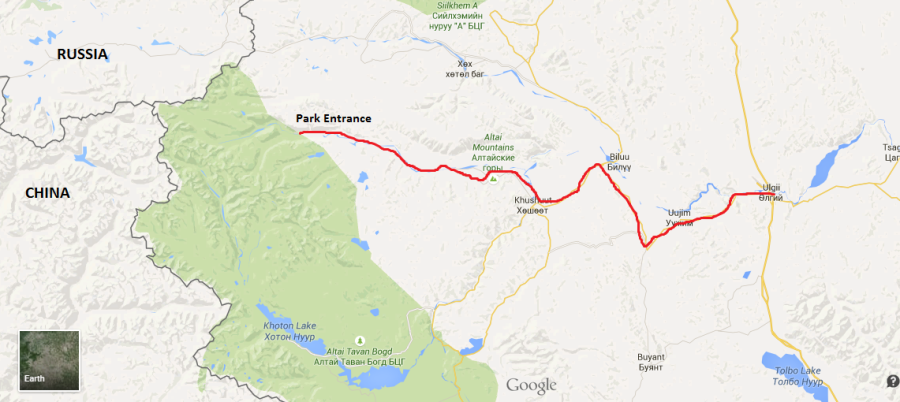

The red line on this map shows the 180 kilometre route we took from Olgii to the entrance of Altai Tavn Bogd National Park.

The red line on this map shows the 180 kilometre route we took from Olgii to the entrance of Altai Tavn Bogd National Park.

The drive from Olgii to the national park was supposed to take about 5 hours but ended up taking closer to 8, including a stop off at our driver’s house for tea. Our driver lived in a small village called Tsengel, located about 70 kilometres east of Olgii, on the way to the national park. With a population of about 2,000, Tsengel is the last major settlement before the national park. The remaining 110 kilometres involved driving entirely off-road over very rough terrain through the remote Tsagaan Gol river valley.

The inside of our UAZ as we drove through the Tsagaan Gol.

The inside of our UAZ as we drove through the Tsagaan Gol.

The “road” was quite rough going.

The “road” was quite rough going.

Like most parts of rural Mongolia, animal husbandry is the main source of livelihood for most inhabitants of Bayan Olgii province, including the few who live in the scenic but extremely remote Tsagaan Gol river valley. There are no electric power lines here or any other kind of industrial infrastructure.

Like most parts of rural Mongolia, animal husbandry is the main source of livelihood for most inhabitants of Bayan Olgii province, including the few who live in the scenic but extremely remote Tsagaan Gol river valley. There are no electric power lines here or any other kind of industrial infrastructure.

There are also very few automobiles in the valley. We didn’t pass one during the nearly 4 hours we spent driving through it.

There are also very few automobiles in the valley. We didn’t pass one during the nearly 4 hours we spent driving through it.

A herd of Bactrian camels in the valley. A common domestic animal in Mongolia, Bactrian camels are extremely hardy beasts, able to withstand both the extreme temperatures of arid desert and steppe climates as well as harsh mountainous terrain.

A herd of Bactrian camels in the valley. A common domestic animal in Mongolia, Bactrian camels are extremely hardy beasts, able to withstand both the extreme temperatures of arid desert and steppe climates as well as harsh mountainous terrain.

One of the most remarkable sights we saw in the valley were these ancient Kurgan stele or monoliths. These carved anthropomorphic stone slabs mark the grave sites or “kurgan” of the Gokturks, a nomadic confederation of pre-Islamic Turkic peoples originally from medieval Inner Asia who established the Turkic Khaganate in the 6th century CE, a vast empire that spanned the territory of the present day post Soviet independent Central Asian states (the “Stans”) and Mongolia. The Gokturks were practitioners of Tengrism, “a Central Asian religion characterized by features of shamanism, animism, totemism, both polytheism and monotheism, and ancestor worship”.

One of the most remarkable sights we saw in the valley were these ancient Kurgan stele or monoliths. These carved anthropomorphic stone slabs mark the grave sites or “kurgan” of the Gokturks, a nomadic confederation of pre-Islamic Turkic peoples originally from medieval Inner Asia who established the Turkic Khaganate in the 6th century CE, a vast empire that spanned the territory of the present day post Soviet independent Central Asian states (the “Stans”) and Mongolia. The Gokturks were practitioners of Tengrism, “a Central Asian religion characterized by features of shamanism, animism, totemism, both polytheism and monotheism, and ancestor worship”.

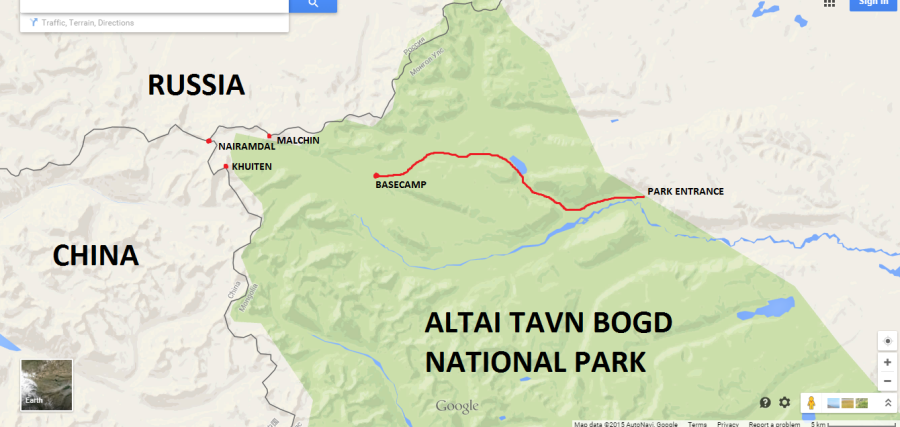

Altai Tavan Bogd National Park

Altai Tavn Bogd National Park is the large green patch near the centre of this map along the border with China. Note that the squiggly red line in the middle is the 38 kilometre stretch of border between China and Russia that separates Mongolia from Kazakhstan.

Located in the remote northwestern corner of Bayan Olgii aimag (province), which is in turn located in the remote northwestern corner of Mongolia, Altai Tavan Bogd National Park spans 6362 square kilometers of pristine alpine wilderness right on the border of both Russia and China. The western boundary of the park marks the Chinese border, while the northern boundary marks the Russian border. Tavan Bogd means “Five Saints” in Mongolian and refers to the five highest peaks inside the park, which includes Mongolia’s highest peak, Khuiten Uul (“Cold Mountain”) at 4,376 metres. The summit of Khuiten also marks the Sino-Mongolian border. The “Five Saints” belong to the Altai mountain range of Central Asia, which spans Mongolia, China, Russia and Kazakhstan. In addition to the “Five Saints”, the park also includes several stunning alpine lakes, as well as three areas containing thousands of ancient petroglyphs and Turkic monoliths, which are listed together as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The park is also home to an abundance of wildlife, including argali (a rare, large-horned species of wild sheep), ibex (a wild goat with long scimitar-shaped horns), deer, moose, wolves, foxes, lynx, brown bears, and even snow leopards. Another attractive feature of the park is the almost complete lack of anthropogenic influence on the landscape; for instance, there are no paved roads, fixed paths or signs. Visitors have to be fully self-sufficient and able to read a topographic map!

We didn’t arrive at the entrance to the park until just after 2pm, which was quite a bit later than we had expected (we had hoped to arrive before noon). Actually, our driver didn’t even drop us at the official entrance to the park, but instead stopped at a local herders wooden cabin, which was located at least 3 kilometres from the park entrance. We didn’t know this at the time, otherwise I would have asked him to drive us right up to the park entrance, since we had paid a king’s ransom for the ride. The main purpose of visiting the park was to try to climb Mongolia’s highest peak, which meant we still had to hike to basecamp. From the park entrance it was a 14 kilometre hike to the basecamp of Khuiten Uul, which we wanted to do that day, so adding a few more kilometres to the hike wasn’t ideal. Since it was already quite late in the day to begin such a hike, I think our driver stopped at the cabin because he expected we would stay a night there and begin our hike the next morning. Dion and I were adamant about leaving as soon as we stepped foot out of the jeep though and even refused an offer of tea with the driver and the residents of the cabin, which in hindsight was probably a bit rude. Just after setting off, I decided to take a couple of things out of my bag, including a small bottle of vodka, to lighten the load a bit, so I walked back to the cabin and asked if I could leave them there, which the owner kindly obliged. Even after shedding 1-2 kg of unnecessary weight though, my bag probably still weighed somewhere between 20-25 kg.

Entrance to Altai Tavn Bogd National Park. There was only this sign to indicate that we were at the entrance of the park, there were no buildings or park staff to greet us. We had to apply for a border permit from the Mongolian military to enter the park, and were told that park rangers or border patrol soldiers inside the park might approach us at any time and ask to see the permit at anytime, but we didn’t see either during the 4 days we were inside the park.

Entrance to Altai Tavn Bogd National Park. There was only this sign to indicate that we were at the entrance of the park, there were no buildings or park staff to greet us. We had to apply for a border permit from the Mongolian military to enter the park, and were told that park rangers or border patrol soldiers inside the park might approach us at any time and ask to see the permit at anytime, but we didn’t see either during the 4 days we were inside the park.

After just a few kilometers, we were really beginning to feel the weight of our packs.

After just a few kilometers, we were really beginning to feel the weight of our packs.

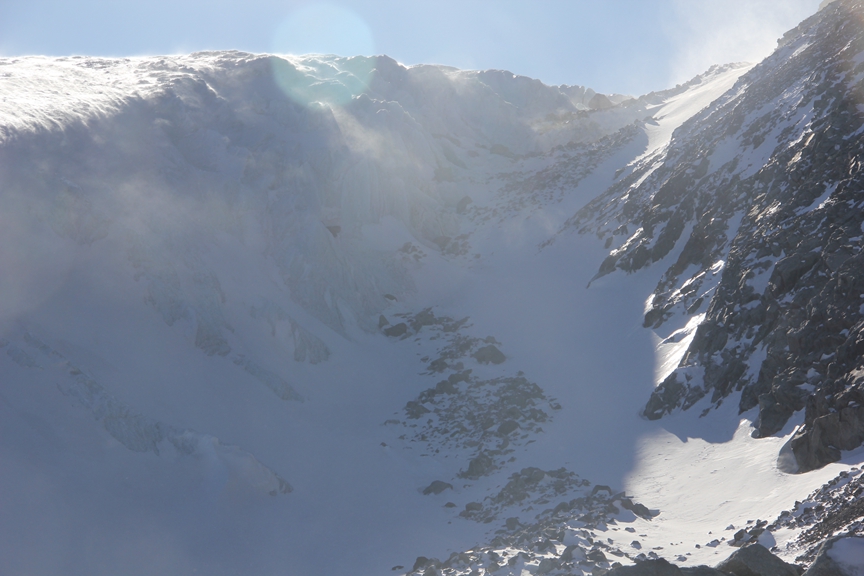

The scenery was absolutely spectacular!

The scenery was absolutely spectacular!

The snow was quite deep in places, which really slowed us down. It was also slightly frustrating and unnerving because we never knew when we were going to suddenly sink up to our knees or even higher. Some of the snow was hard enough to walk right on top of but you could just as easily sink up to your waist at any given moment; trying to crawl out with our heavy packs was tiresome and time-consuming.

I must have sunk up to my knees like this at least 3 dozen times the first day.

I must have sunk up to my knees like this at least 3 dozen times the first day.

Dion slogging his way across a snow field. Neither of us were quite sure if we were going the right way since there was no path to follow.

Dion slogging his way across a snow field. Neither of us were quite sure if we were going the right way since there was no path to follow.

Luckily I had bought a fairly detailed 1:500,000 scale topographic map of the area at a mountaineering store in Ulaan Baatar called Sevin Summits, which was indispensable for navigating through the park without a guide. There was absolutely no sign of a path anywhere; instead we had to navigate using mountains as landmarks. The owner of Blue Wolf Travel, a travel company and hostel in Olgii, the capital of Bayan Olgii province, had marked the route on our map with a pen but it was still a challenge to navigate because of the size of the area and complete lack of a path or any signage to indicate that we were going in the right direction. We weren’t really afraid of getting lost but we worried that we weren’t taking the most direct route, and didn’t want to waste precious daylight on necessary detours. For instance, when we were crossing a large snow field, I suddenly stepped into a pool of ice-cold water hidden beneath the snow, completely submerging my boot. Shocked, I looked around and quickly realized that I had come to a large swathe of still, shallow water. I tried to go around it but discovered to my dismay that the water stretched for at least a kilometer to my left and right. I could see that it was only about 30 metres across though, so I decided to try my luck and walk as nimbly as I could over patches of ice and snow. Unfortunately, this didn’t really work and I ended up sinking into the water at least every other step. If there had been a clearly marked path though, I probably wouldn’t have stumbled into this predicament. Thankfully, my gore-tex lined mountaineering boots are fairly water-resistant, so my feet stayed relatively dry, although my boots froze solid that night. Dion had earlier decided to take a longer route across the snow field, so he didn’t have the same problem, but his detour added about an hour to his hike.

Once I was back on dry land, I quickly found a patch of grass to pitch our tent. It was already after 7 and we had been hiking for 5 hours straight, with the exception of a few 5 minute water breaks. Dion and I had agreed earlier to stop hiking by 7pm so that we would have enough time to pitch our tent and make camp before sunset. It was the end of April and we were at an altitude of about 3,000 metres, so the temperature really began to dip once the sun began to set. It was also very windy, so the wind chill made it feel quite a bit colder. In fact, our first night in the park was much colder than expected. I had a down sleeping bag that’s supposed to keep me comfortably warm down to minus 10 Celsius (and alive at – 20), so I thought it would be fine to just sleep in my long underwear, but I was wrong. The temperature was at least 10 degrees during the day in the sun, but it dropped well below – 10 at night, so I had to get up in the middle of the night and put on all my layers to keep warm, which was a bit of a nuisance. My discomfort was also compounded by a chest cold that was getting worse, to the point where I worried that I may not be well enough to climb the mountain.

Our camp site on the first day. You can see the large, meandering swathe of shallow water in the background. The water was frozen solid when we woke up the next morning but this photo was taken at about 10am, so the sun was already beginning to melt the ice.

Our camp site on the first day. You can see the large, meandering swathe of shallow water in the background. The water was frozen solid when we woke up the next morning but this photo was taken at about 10am, so the sun was already beginning to melt the ice.

We decided to sleep in a bit the first morning and take our time packing up because we thought we only had a short hike ahead of us to reach basecamp. Once again, we were wrong. It took another 6 hours of nonstop hiking before we finally reached basecamp early that evening, which was somewhere between two to three times longer than we had expected. Part of this was because of the snow. Deep snow in many areas had slowed us down considerably and concealed any sign of a foot path that would have offered a more direct route. Instead, we had to more or less wing it with the help of the map. Again, we knew were going in the right general direction but had to occasionally readjust our route, which involved quite a bit of meandering and even backtracking.

The scenery was even more spectacular on the second day!

The scenery was even more spectacular on the second day!

We even saw fresh bear tracks, which added to the excitement of being in a pristine alpine wilderness.

We even saw fresh bear tracks, which added to the excitement of being in a pristine alpine wilderness.

Dion walking on top of a moraine next to the 22km long Potaniin glacier, which leads to the foot of Khuiten Uul.

Dion walking on top of a moraine next to the 22km long Potaniin glacier, which leads to the foot of Khuiten Uul.

A good vista of Khuiten Uul. The cairn on the lower left of the photo is just above basecamp.

A good vista of Khuiten Uul. The cairn on the lower left of the photo is just above basecamp.